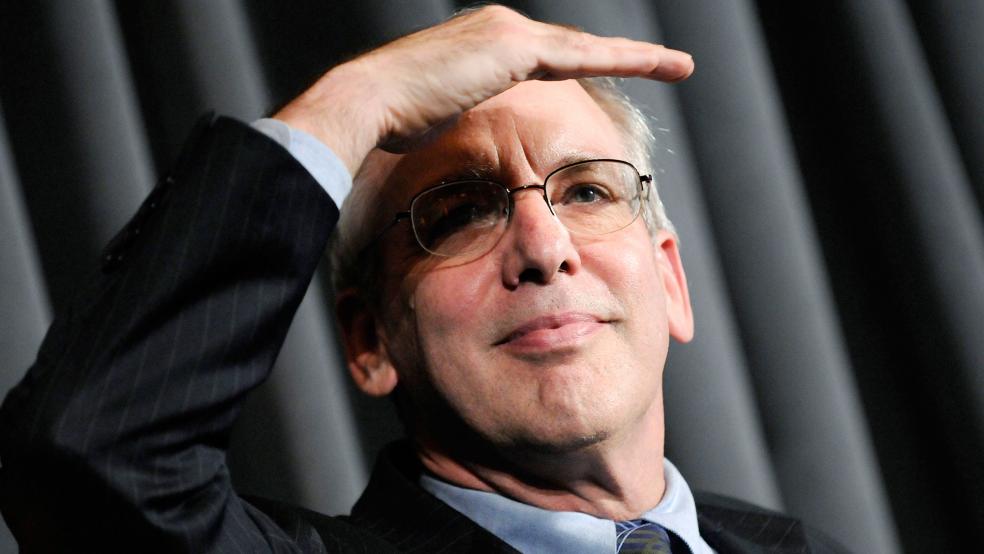

In a speech this week, New York Federal Reserve Board President William Dudley addressed pervasive misconduct within the financial industry, refusing to dismissively lay the blame on a few bad apples. “The problems originate from the culture of the firms, and this culture is largely shaped by the firms’ leadership,” Dudley said.

He offered some interesting suggestions on industry compensation practices, but his main message was a warning: If nothing changed, regulators would have to conclude that large financial institutions are too big to manage, and “that your firms need to be dramatically downsized and simplified so they can be managed effectively.”

Related: Are Regulators About to Let Another Bank Get Too Big to Fail?

These were notable words from someone in the actual position to undertake a big bank breakup. But Dudley added a little caveat, as typical for such speeches: “What I have to say today reflects my own views and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve System.” He would have to say that, because the organization he runs hasn’t practiced what he preached.

In recent weeks, multiple allegations show that the New York Fed, the largest and most important of the regional Federal Reserve banks, would rather allow financial institutions to conduct their business unencumbered than break them up. Last month, former employee Carmen Segarra released secretly recorded tapes to public radio’s This American Life, showing that the New York Fed worked diligently to avoid confrontation with Goldman Sachs over the investment bank’s admittedly “shady” practices. This week, more embarrassment arrived in a Federal Reserve Inspector General’s report.

The report concerns the disastrous “London Whale” trade, carried out in 2012 by the Chief Investment Office of JPMorgan Chase, which lost the bank over $6 billion. The Inspector General surveyed the years leading up to the trade, and while the public was only treated to a summary rather than the full report, it contains enough information to present the failure of the New York Fed’s bank supervision practices.

Employees at the New York Fed identified risks at the Chief Investment Office as far back as 2008. They planned multiple examinations of the unit’s proprietary trading activities (which have since been limited by the Dodd-Frank Act’s Volcker rule). And a separate Federal Reserve team similarly recommended a “full-scope investigation” of the CIO in 2009.

But the New York Fed never actually performed the examinations, nor did officials there coordinate with their colleagues at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to investigate. Worse, they blamed this partially on a reorganization of supervisors at JPMorgan, which “resulted in a significant loss of institutional knowledge regarding the CIO.”

Related: Wall Street Is Betting Big on Cory Booker

We don’t know what the New York Fed might have found at the CIO, and whether it might have prevented the London Whale trade. But you can’t find anything if you don’t look. And a deeper probe may have revealed the control failures at JPMorgan, where executives remained ignorant of the risks being taken at subsidiary offices.

This is eerily similar to the mindset from top officials on the Carmen Segarra tapes. The New York Fed seems to define “supervision” as writing a stern letter, or bringing up issues in a meeting with bank executives, without follow-through. Lower-level employees who uncover potential problems at the supervised institutions get countermanded somehow, and no real oversight develops. And if someone leaves the supervision unit, any knowledge they had about the inner workings of the bank goes with them.

In the This American Life tapes, the discussion between Carmen Segarra and her boss Mike Silva over Goldman Sachs’ conflict of interest policy best reflects this tension. Not only does Silva alter his stated position on whether Goldman has a conflict of interest policy, he demands that Segarra change her view as well. “Why can't we just say they have bits and pieces of a policy,” Silva asks Segarra, “but they have to dramatically improve it?” It’s pretty clear that someone told Silva to back off, and remove all traces of questioning Goldman on this issue. When Segarra refused, she was fired.

We don’t know who forced Silva’s hand, or why. But it fits the pattern of how initial supervision questions at the line level vanish into the ether at the New York Fed. We don’t know who gave the order to prevent further investigation into JPMorgan’s investments, either. And that speaks to the persistent problem of how the opaque institution is structured.

A Troubling Lack of Transparency

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors is a public institution, which writes banking rules and enacts monetary policy. But the 12 regional banks, which carry out regulatory examinations, are privately run. The local banking industry and other corporate interests choose the majority of the regional bank boards, who subsequently select a president. Unsurprisingly, those presidents often reflect the business management perspective of those who choose them. Bill Dudley, the New York Fed president, spent his career as chief economist for Goldman Sachs.

This public/private hybrid leads to a lack of transparency about the regional banks and their activities. The New York Fed, which because of the presence of Wall Street has by far the most power of the regional banks, routinely exempts itself from public disclosure requirements. During the AIG trial going on in Washington, the New York Fed has refused to reveal to opposing counsel the so-called “Doomsday Book,” a blueprint that lays out the emergency powers and legal boundaries for how to deal with financial crises. Even the Inspector General report on the London Whale was abridged.

Related: CFPB Hits a Bad Bank Where It Hurts

Some secrecy may be expected at a government institution, but not necessarily for one that seems controlled by Wall Street, for the benefit of Wall Street. This allows top executives and their staff to manage the affairs of the New York Fed without challenge, even when they violate the spirit of their bank supervisory mission.

In response to the Segarra tapes, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) called for Banking Committee hearings and an investigation into the New York Fed, and House Democrats have made formal requests as well. So far, committee chairs have given no final word, according to Senate sources. The White House has said nothing. Now, Americans for Financial Reform (AFR), the umbrella organization of progressive and labor groups on this issue, has gotten involved in demanding hearings. It’s a problem when the “key on-the-ground supervisor for Wall Street banks,” as AFR puts it, cannot be trusted to carry out its functions.

Perhaps a bigger question is: Who is protecting the New York Fed, in the same way that they’ve protected Wall Street through their unwillingness to act? Why shouldn’t they have to answer for their lapses in supervising the same banks that helped generate the financial crisis?

Captured regulatory institutions make the entire financial system more unstable. Regardless of Bill Dudley’s big talk, there’s something wrong at the heart of the New York Fed, and we need to expose it.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: