Republicans have been clamoring to rescind billions of dollars in additional funding provided for the Internal Revenue Service as part of last year’s Inflation Reduction Act. They succeeded to an extent as part of the recent deal between House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and President Joe Biden to raise the debt limit, which also clawed back $21.4 billion from the tax agency.

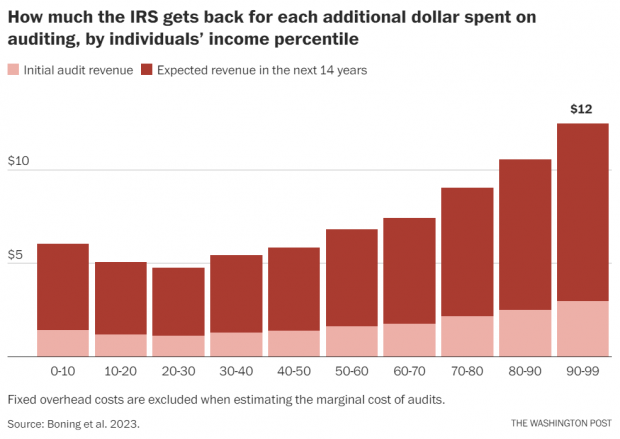

A new study suggests that deal could be costly. Researchers at the Treasury Department, Harvard University and The University of Sydney looked at IRS data for about 710,000 in-person audits. They found that audits generate a substantial return for the government — and while audit costs rise for those with higher incomes (because wealthy people typically have more complicated tax filings) the returns rise even more. Every additional dollar spent on auditing taxpayers in the top 10% of earners generates more than $12 in revenue for the government.

Washington Post Columnist Catherine Rampell lays out another way to think about the new data: “On average, the direct revenue collected from audits exceed costs by a factor of 2 to 1,” she writes. “But, that payoff varies by income. For money spent auditing the bottom half of taxpayers, the IRS only roughly broke even. Meanwhile, the agency pulled in $3.18 for each dollar spent auditing the top 1 percent, and $6.29 for the top 0.1 percent.”

The study also found a lasting benefit from the audits: taxpayers who were audited voluntarily pay more taxes going forward — for at least 14 years after the initial audit. “For every $1 an audited person pays during their audit, they pay $3 more on their taxes in the subsequent years,” Harvard Economist Nathaniel Hendren, one of the paper’s authors, tweeted.

The Congressional Budget Office models only modest lasting effects from stepped up enforcement, but the new study finds that longer-term deterrence results in about three times the revenue of the initial audit. Taxpayers either get scared straight or correct unintentional errors they previously made, resulting in higher tax payments over time. “Our finding of significant deterrence effects throughout the income distribution differs from existing CBO scores,” Hendren notes.

Why it matters: “If the IRS spends more money on audits, and those resources actually target high earners, the payoff could be enormous — far greater than has usually been assumed,” Rampell writes. The new research also indicates that auditing top earners is a more efficient way to increase revenue than raising tax top rates. “Which means,” Rampell says, “rather than soaking the rich through higher tax rates, perhaps we should merely enforce existing law.” But if the $20 billion cut to IRS funding comes out of enforcement and audits, it could mean that lawmakers just gave up hundreds of billions more in revenue.