The Dow Jones Industrial Average tested below the 18,000 level on Friday — revisiting a hurdle it first cleared back in December. It's been five months of listlessness for the U.S. stock market as a bevy of concerns weigh on the bulls, from the specter of Federal Reserve interest rate hikes to the situation in Greece and ongoing disappointment with the economic data.

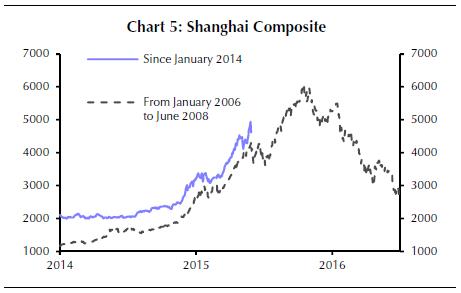

Compare that to the action in China, where the Shanghai Composite is in the midst of an epic rally fueled by cheap money and a massive expansion of margin lending by brokerages. Since December, while U.S. equities have been flat, the Shanghai Composite is up roughly 70 percent as the number of brokerage accounts has quadrupled. Margin positioning has increased tenfold from 2013 levels.

Related: If U.S. Interferes In China’s Land Grab, 'War Is Inevitable'

More recently, it's been a rollercoaster. The Shanghai Composite lost 8 percent over three days in early May, rose 20 percent in less than three weeks and then came within a hair of the 5,000 level before falling 6.5 percent on Thursday. It was down another 4.1 percent in mid-day trading on Friday before recovering to end the day roughly flat.

What comes next?

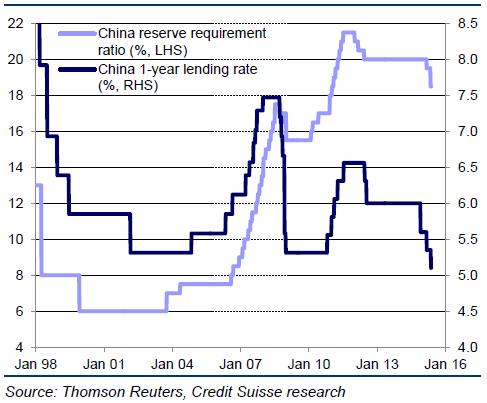

It's pretty clear that Beijing is consciously inflating this bubble as an answer to a breakdown in its debt-driven, investment-focused, exports-dependent economic growth engine. The bad debt scare of early 2014 — remember "Credit Equals Gold #1"? — led to looser monetary policy via a series of interest rate cuts and less stringent reserve requirement ratios courtesy of the People's Bank of China.

Since February, the PBoC has cut the reserve requirement ratio by 1.5 percent. That works out to more than $322 billion of bank lending liquidity being unleashed. Moreover, it has cut its benchmark interest rate by 0.9 percent since November. As shown in the chart above, that takes China's interest rates below the lows reached in the wake of the 2001 and 2008 downturns.

Further easing measures are expected. Deflation is becoming a persistent problem in the Middle Kingdom. The GDP deflator is negative (-1.2 percent) and factory gate prices are falling fast (-4.6 percent). Capital outflows have been a problem, as banks repay increasingly expensive foreign loans denominated in a stronger U.S. dollar, thereby draining liquidity from China's financial system.

And relative to the slowdown in GDP growth, China's monetary policy is actually the tightest it's been since 1999, according to Credit Suisse calculations.

Related: A Bumpy Road Ahead for China’s $100 Billion Infrastructure Bank

At the end of the day, though, this bubble will be brought down by the same factors that popped the Japanese equity bubble of the 1980s, the Nasdaq tech bubble of 2000 and the U.S. housing bubble of 2007: Fear and overvaluation.

While the index on an absolute price basis is still below the heights reached in 2008, as shown in the chart above from Capital Economics, technical indicators have become stretched, according to Credit Suisse. These include deviations from the 200-day moving average and the level of the Relative Strength Indicator as well as measures of speculative activity such as new trading accounts and exchange volumes. All are at heights that match or exceed what was seen during the last market peak.

Related: China Invites Private Investors to Help Build $318B in Projects

Valuations are high but not as extended based on metrics including earnings yield vs. bond yield, price to earnings and price to book. But it depends on where you look, with big valuation differences in value and large-cap stocks compared with small-cap growth stocks.

Bringing it all together, the team at Credit Suisse believes Chinese stocks are 23 percent overbought and have 15 percent potential downside through the end of the year when denominated in U.S. dollars. Profit margins and value creation continue to decline as China's productivity growth lags real, inflation-adjusted wages and product price deflation worsens. Stock price growth has also meaningfully decoupled from earnings revisions, which remain deep in negative territory.

A wild card in all this is whether the MSCI decides to include mainland A-shares in its emerging market equity index. The decision is due June 9 and, if voted in the affirmative, could result in a flood of fresh offshore cash pouring into Chinese shares. Capital Economics believes any initial A-share weighting will be kept low to avoid pricing dislocations.

Related: What’s Pushing Russia and China into Each Other’s Arms

MSCI, like all indexers, feels compelled to chase hot areas. The MSCI China index is up 35 percent over last year in dollar terms, making China the best performing market within the MSCI's emerging market category by a wide margin. (The second best performance comes from the Philippines, which is up 14 percent.) When you remove the influence of China from the overall MSCI EM stock index, emerging market stocks are actually lagging developed economy stocks by 3 percent year-to-date.

On top of everything else, Beijing will want pump more cheap money into the economy in an effort to reverse a slowdown in money supply growth to its lowest level in at least two decades. Combined, it all means that despite recent turbulence, Chinese stocks likely have room to run even higher from here before the bubble pops — even if there are a few nasty bumps along the way.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: