It's been a long time coming, but it's finally here: The balance of power has finally started to shift away from big business and corporate profits toward American workers. Should the shift continue, working families should soon start seeing a meaningful increase in real incomes for the first time since in roughly 10 years.

This is the takeaway from the government's latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTs, which is one of Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen's favorite economic datasets. And for good reason. Its insight into the number of job openings and the pace of hiring, firing and job quits provides a unique window into the dynamic between employee and employer that is as the center of what most people consider a "strong economy" to be.

Related: Middle Class Jobs Aren’t Gone; They’ve Just Moved

More simply, if folks feel confident enough to tell their boss to shove it, comfortable in the ease of finding a new and probably better job, then it's happy days. This is the opposite of the old joke about the difference between recessions and depressions: In the former, your neighbor loses his job, in the latter, you lose yours.

Throughout the depths of the financial crisis, and in the years of recovery that followed, the power dynamic remained in the hands of HR hacks and middle management. Raises were foregone. Benefits were cut as earnings growth swelled, at least initially, via lower labor costs. And workers couldn't say anything lest they joined the army of long-term unemployed that watched in horror as extended jobless benefits expired. Most were just happy to have a job.

US Job Openings Rate: Total Nonfarm data by YCharts

Now, the JOLTs data suggests the tide has turned in a big way. The number of job openings increased 3.4 percent to 5.1 million in February while the job openings rate — calculated as the ratio of openings to employment and openings — increased to 3.5 percent. Both are near the respective all-time highs of these metrics dating back to the end of 2000.

J.P. Morgan economists believe more job openings could soon lead to higher earnings. Anecdotally, we've already seen evidence of this with entry-level employers like Walmart (WMT) and McDonald's (MCD) grabbing headlines with pay and benefit increases.

Related: How McDonald’s and Walmart Wage Hikes Can Boost the Economy

The kicker is that the JOLTs data reveal after years of being spoiled by a deep and willing pool of available labor to hire from, employers have suddenly found the pool is running dry just as the need to ramp up their headcounts hits. (The dynamic is connected to modest capital expenditures in this business cycle, which is dampening labor productivity and making the economy more dependent on more labor to increase output).

US Hires Rate: Total Nonfarm data by YCharts

As a result, the pace of hiring is beginning to lag the pace of job openings. The divergence reflects structural inefficiencies in the jobs market: unmatched or inadequate skills amongst the unemployed but also lingering issues like underwater homeowners unable to move.

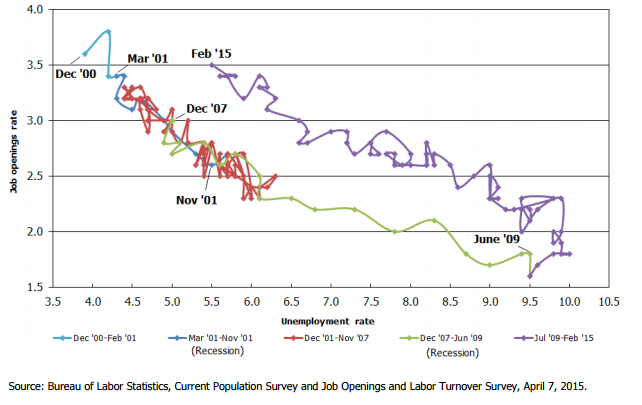

This takeaway is supported by what's happening in a measure known as the Beveridge curve, which compares the unemployment rate to the job openings rate. When the labor market is functioning smoothly, with workers and jobs quickly matched up, the curve shifts leftward. When frictions are in play, as they are now, it shifts rightward.

What this means is that if the job market was working and skills were matched and employers and employees were hooking up with the ease of Tinder-swiping teenagers, the unemployment rate would be near 4.0 percent instead of the 5.5 percent it's at now.

Related: Is the Unemployment Rate Just a ‘Big Lie’?

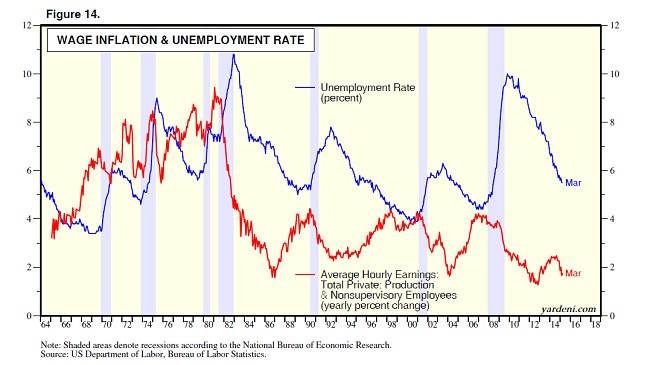

As we should expect, this classic supply-demand imbalance should increase the cost of what is an increasingly scarce good: Employable, skilled, well-qualified workers. This should help lift average hourly earnings out of their winter slump and improve from their current 1.8 percent annual growth rate to the highs near 4.0 percent hit during the last two economic expansions.

Indeed, Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research posits that perhaps the March slowdown in payroll growth (which rattled equity futures in the holiday shortened Good Friday session) may be the result of the severe winter weather that hit much of the country again last month, if the conditions discouraged employers from interviewing and hiring. But if it is in fact being driven by a skills mismatch, than payrolls gains should keep disappointing as spring rolls on.

What is crystal clear is that an acceleration in wages has been far too long in coming, as shown in the chart above. Despite a rapid tumble in the unemployment rate (which, as we know from the Beveridge curve should be even lower) wage inflation has returned to early 2013 levels. The new data suggests this is finally about to change.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: