Last week's Federal Reserve policy announcement was a big one. In response to a tightening in the labor market, the Fed set the stage for an interest rate hike possibly as soon as June by removing the "patient" language from its statement. But it also acknowledged recent economic weakening and softness in inflation (caused by falling energy prices and a rising dollar).

The Fed statement itself was largely boilerplate, noting further improvement in the labor market and reasonable confidence that inflation would move back to the Fed's 2 percent target — an expectation that may have been reinforced with Tuesday’s Consumer Price Index release showing another 0.2 percent uptick in February. The bigger story was what happened with the Summary of Economic Projections or "dot plot" estimate of where interest rates will be over time. Fed policymakers dramatically cut the median estimate of where rates will be at the end of the year to 0.6 percent from 1.2 percent previously.

Translation: The Fed is only looking for two rate hikes this year, down from four back in December. This could be too optimistic.

Related: Will Fed Rate Hikes Cost You in Higher Taxes?

The end-2016 interest rate estimate was cut to 1.9 percent from 2.5 percent and the end-2017 was cut to 3.1 percent from 3.7 percent. In addition to cuts to its 2015 GDP growth forecast, headline inflation forecast and the "full" employment rate estimate, this suggests the Fed is suddenly looking a lot less hawkish on monetary policy.

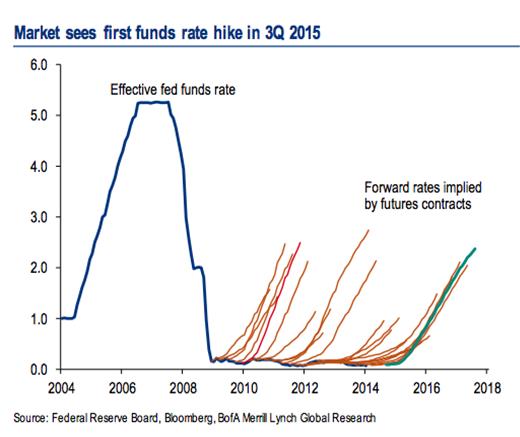

This change continues a long tradition of Fed optimism about the future being marked down. The chart above shows how Fed guidance on the path of interest rate hikes has been consistently walked back from year to year. Reality never seems to live up to the forecasts.

Early in the recovery, the futures market believed interest rates would start climbing in 2009. Yet we're in the midst of the eighth year of interest rates near 0 percent. Each year that goes by, the market and the economy becomes more dependent on the monetary morphine as the risks of withdrawal increase — something the Bank for International Settlements in Basel warned of back in 2010.

Yet every time the Fed tries to wean off the cheap money junkies — I'm not talking outright tightening but merely slowing the flow of stimulus by ending its QE1, QE2 and QE3 bond-purchase programs — the economy slows, inflation falls, the stock market rattles and the Fed is forced to dole out more. It happened in 2010. It happened in 2011. And it's happening again now.

Related: The Middle Class Is Struggling in All 50 States

This is not occurring in a vacuum. So far this year, global central banks have cut interest rates 27 times. The European Central Bank has unleashed a long-awaited sovereign bond-buying stimulus program. The Chinese are talking of new stimulus efforts.

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans, in a recent paper, noted that with rates near 0 percent the Fed needs to be absolutely certain of the strength of the economy before raising rates. In his words, the current situation means "a delayed liftoff is optimal." His fear is that if the Fed needed to restart its bond buying program — under the guise of a "QE4" — after raising rates too soon and sending the economy back into recession, that it may not be effective enough this time.

Waiting brings its own risks, however.

Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic department at the BIS, cautioned that the low rate environment could result in political instability and create a world in which monetary "easing begets easing," leading to a situation where "technical, economic, legal and even political boundaries may well be tested."

Now, there is growing concern — as recently discussed by officials at the Bank of England — about the side effects of interest rates falling into outright negative territory, which is happening in parts of Europe. Sweden, for example, cut its policy rate to -0.25 percent last week. The risk is that the mechanisms supporting the financial system — bank deposits and short-term money markets — start to break down as the relationship and flow of remuneration between depositor and lender become murky.

This brings to mind something former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke let slip at a big-ticket dinner earlier this year, as reported by Reuters: Interest rates would not return to normal — at around 4 percent — in his lifetime, as the Fed would wait longer and move slower on rate hikes than many believe.

Analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch believe the Fed won't act until September at the earliest with a risk that if inflation doesn't bounce back by then, the first rate hike could be pushed into 2016. Aneta Markowska, chief U.S. economist at Societe Generale, is looking for a rate hike in June and one in the fourth quarter. Joseph LaVorgna at Deutsche Bank believes liftoff will occur in September with another rate hike later in the year. Morgan Stanley's chief U.S. economist, Ellen Zentner, doesn't expect any move on rates until 2016 as inflation continues to move away from the Fed's 2 percent target and significant wage gains have yet to materialize.

Related: America Is In Deflation. So What?

The only thing that could force the Fed's hand at this point would be a further tightening of the labor market leading to significant wage inflation. Deutsche Bank notes that the Fed's new unemployment rate forecast is only implying modest job growth and a drop in the unemployment rate from 5.5 percent now to 5.1 percent or below by 2017.

At the current pace, we will hit that level by the end of this year — which could be the catalyst that finally forces the Fed to end the era of 0 percent interest rates that started in 2008. But don't hold your breath because, as history has shown dating as far back as the monetary debasement that helped bring down the Roman Empire, easy money is hard to quit.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: