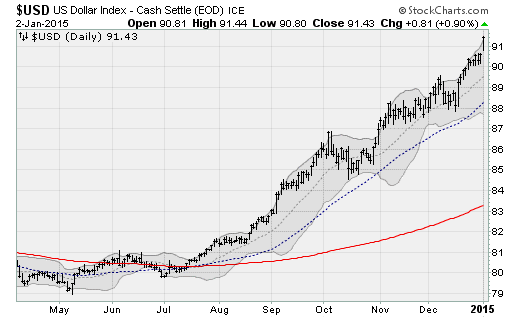

As the calendar flips into 2015, investors are looking ahead to what the big theme of the New Year will be. On Friday, we got a taste: The U.S. dollar climbed 0.9 percent to return to highs not seen since 2005. From the lows of 2008, the greenback is up more than 28 percent and it soared nearly 13 percent in 2014 alone.

For most, the weakness of the currency still feels fresh. The Federal Reserve's rock bottom interest rate policy is in its eighth year. The national debt stands at $18 trillion and rising. Family friends, preparing to send their oldest daughter on a study abroad trip to Greece, recently complained about the rate of exchange with the euro — unaware that the trip to Athens was being funded on the best terms since Barack Obama was a fresh-faced senator from Illinois.

Related: Government Leadership, Not the Economy, Is Now American’s Top Concern

The dollar sits at the nexus of all the big themes set to play a role in the months to come: OPEC's ongoing oil price war against U.S. shale producers, new pressures in the Eurozone and the approach of the Federal Reserve's first interest rate hike in nine years.

That'll have some clear benefits, as the proponents of a strong dollar have long espoused. But the end of the dollar's decade-long slumber will bring some dangerous downsides as well.

Aside from national prestige and cheaper flights to the Aegean, the dollar's rise is tightly linked with the halving of energy prices over the last six months, with clear benefits for middle-class families. Estimates by Credit Suisse put the benefit to the average household of the decline to date at about $1,000 a year for a household earning $40,000.

Since the dollar is used in the vast majority of cross-border commodity trades, it maintains a close inverse correlation to the price of crude oil. As crude oil fell from its summertime high of $107.68 a barrel to close at $52.81 last week, the dollar zoomed to the upper end of the sideways trading range established back in 2004.

It's on the threshold now, with another 1 percent rise enough to push it out of its long funk and return it to 2003 levels. That, in turn, would further pressure energy prices towards the 2009 recession lows of $33.55 a barrel.

Related: Why Big Oil Needs a Bailout in New OPEC Price War

The extra boost to living standards will go a long way toward boosting stagnant inflation-adjusted incomes. Even if nominal wages remain flat (which doesn't seem likely, given a unemployment rate that's falling fast and business surveys pointing to a tightening job market), purchasing power will rise.

That'll be great news for one area of the economy that's been lagging behind: housing. The latest S&P Case-Shiller Home Price Index data, from October, showed home price gains reaccelerating out of a summertime funk on a month-over-month basis. Since housing is the single largest asset class owned by most middle-class Americans, continued gains would lift wealth and further support spending.

Now, for the downsides.

Emerging market economies have collectively borrowed nearly $6 billion according to The Telegraph’s well-informed Ambrose Evans-Pritchard. That worked great when the Fed was committed to 0 percent interest rates and was printing $85 billion a month to buy up bonds and mortgage-backed securities. But with the first tightening cycle in nearly a decade set to begin in the next several months, it will become harder and more expensive to roll this debt over.

The more the dollar rises, the more emerging market and commodity exporting countries will feel deflationary pressures. The more that happens, the more compelled they will feel to let their currencies devalue to generate inflation and boost profitability. But that will only further encourage the dollar to strengthen.

Related: 6 Top Value Picks for 2015 from Stock Newsletter Gurus

The Bank for International Settlements, the central bank of central banks in Switzerland, recently warned that the situation looks similar to the dollar melt up that led to the Russian debt default and Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. This period also coincided with the last U.S. corporate profits recession in 1998, driven by a drop in crude oil prices and the drop in earnings that results from foreign profits being repatriated into stronger dollars.

The S&P 500 suffered a 20 percent drop that year before zooming another 50 percent-plus to the dotcom era highs. (It's worth noting that the economy and job market kept on chugging during this period.)

Just look at the damage being felt by the countries of the former Soviet Union, with Turkmenistan devaluing by 18 percent on Thursday, with similar declines seen in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Belarus is suffering political unrest. Expect more of this.

The situation in Europe feeds into this dynamic. The renewed political unrest in Greece, with the anti-bailout Syriza party maintaining a lead in the polls ahead of snap elections on Jan. 25, could call into question the financial contagion defenses of the Eurozone.

German officials seem confident that if Greece restored the drachma and exited the euro, markets wouldn't immediately pivot to put pressure on too-big-to-fail countries like Italy and Spain. Investors seem confident that Greece's simmering rebellion against its bailout program won't undermine efforts by the European Central Bank to push ahead with a stimulus program buying government bonds. Both assumptions will soon be tested.

The euro's 0.8 percent drop on Friday, to lows not seen since 2010, is a taste of things to come.

Putting it all together, turmoil in foreign bond and currency markets, Fed rate hikes and falling oil prices will continue to boost the U.S. dollar in a self-sustaining cycle. That could pinch corporate profits and unnerve stocks, rattling investors as middle-class families enjoy a lift.

As for the daughter headed to Athens, she's about to see firsthand how major shifts in the world's most important currency can play out. It's not all good or all bad, but a mixture of consequences. She'll be happy about the fat grip of euros in her pocket and cheaper airfare, but troubled by the protests sure to return to Syntagma Square as the birthplace of democracy considers voting away its debts.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: