Last week, the Federal Reserve announced an end to its quantitative easing program. This brings up the obvious question, what is next for the Fed? Before getting to that, here are a few notes on quantitative easing and what the Fed’s announcement means for the economy.

First, the Fed’s policy of “accommodative financial conditions” has not ended. The Fed believes that it is the accumulated size of its balance sheet that matters most, not the relatively small changes that occur month to month with quantitative easing.

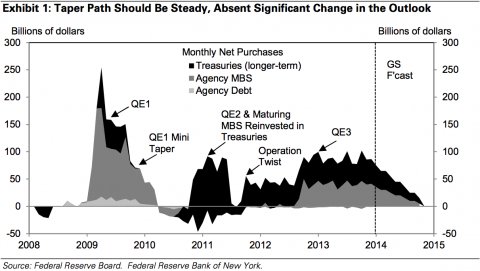

How much has the balance sheet grown? When the Great Recession hit, the Fed’s balance sheet was approximately $700 billion dollars, and over the course of the recession and recovery, the asset purchases the Fed made through its various quantitative easing programs expanded the balance sheet to over $4.4 trillion at the end of October of this year. The Fed plans to reinvest the proceeds from any financial assets that mature, so the size of the balance sheet will stay relatively constant, at least for now.

Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Keeping the size of the balance sheet relatively stable maintains downward pressure on interest rates, particularly long-term rates, and that is the basis for the claim that the policy remains accommodative. To see why, imagine that the Fed suddenly, say over the course of a single month, sold between $3 and $4 trillion of its financial assets to reduce the size of its balance sheet close to its pre-recession size. That would put considerable downward pressure on asset prices, likely cause a spike in interest rates, and make it much more difficult for the economy to recover. It could even send the economy back into recession.

Related: Is the Fed Wrong Again on Interest Rate Hikes and Inflation?

When the economy is viewed as sufficiently strong and the Fed does begin reducing the size of its balance sheet, it will do so slowly to avoid having such a large impact on asset prices and interest rates. One way to do this would be to stop reinvesting the proceeds from maturing assets. In any case, when it does come time to begin raising interest rates, the Fed will not need to sell a large quantity of assets to lift the economy above the zero bound.

It has other tools to do that, new powers granted during the Great Recession such as paying interest on reserves or the use of “reverse repos.” So the Fed will be able to reduce its balance sheet at a leisurely pace without worrying about its ability to change interest rates.

The second point is that critics of the Fed and quantitative easing – for example those who worried about the inflation problem that never came – have it backwards. The effect of quantitative easing on the economy was not that large, and when demand is substantially deficient, as it is in deep recessions, inflation is not a big concern. When the Fed normalizes policy and finally begins increasing its target interest rate above the zero bound -- something that will only happen when demand and the economy have recovered sufficiently -- the Fed will regain its powers over the economy.

Related: The Fed’s Not So New Role: Champion of the Working Class

Interest rate changes, unlike quantitative easing, have a large impact, particularly increases in interest rates designed to slow down an overheated economy. If the Fed gets its interest rate movements wrong, if it raises interest rates too late, then inflation could be a problem. However, even though the Fed’s power over the economy and the cost of mistakes will be much larger once policy is normalized, many of the critics who spoke so loudly against quantitative easing will likely fall silent.

What is next for the Fed? I don’t believe the Fed’s policy of targeting the federal funds rate in response to changes in output and inflation will change, e.g. to adopt nominal GDP targeting instead. That may happen someday, but for now. something along the lines of a Taylor rule is likely to persist. But I do think there will be changes in the Fed’s operating procedure. Prior to the Great Recession, the Fed was on track to adopt a “corridor system” for setting its target interest rate.

Under this system, the discount rate sets a ceiling on the federal funds rate (the rate that banks pay for overnight loans of reserves from another bank). No bank would pay more to borrow reserves than it has to pay the Fed for a loan, so the federal funds rate cannot rise above the discount rate. At the same time, the Fed’s payment of interest on reserves puts a floor on the federal funds rate.

No bank would loan money to another bank for less than it can get by simply holding onto the reserves and earning interest from the Fed, so the federal funds rate has a lower bound. (The Fed’s reverse repo system effectively does the same thing, but it allows a broader array of financial institutions to receive interest payments from the Fed on the reserves they hold.) By setting the upper and lower bounds fairly close to the target interest rate, the Fed can control the target rate fairly precisely even in the face of unexpected changes in financial market conditions.

Related: Fed Ends QE3, Singles Confidence in U.S. Economy

Finally, a worry about the future. An independent Fed is one of the best ways to prevent inflation and to ensure that policy is (relatively) free of political considerations. During the Great Recession, the Fed’s independence came under pressure, particularly, though not exclusively, from the political right. Legislation was introduced to reign in the Fed’s discretionary abilities on several occasions, but for the most part this was more bark than bite. However, if the Fed continues to discuss topics like inequality, the Fed’s independence could be threatened.

To be clear, I believe the Fed should discuss the relationship between issues like inequality and monetary policy. In what way has policy contributed to the problem, for example, and how might that be changed in the future without hampering the Fed’s ability to respond to economic problems? Same for the deficit, the Fed should explain how monetary policy and the budget deficit are related. But to go beyond that and say, for example, how large the deficit should be or how equal incomes should be crosses the line into the political arena and risks a backlash that could endanger the Fed’s independence. That would be a mistake. I don’t believe the line has been crossed yet, but it’s certainly something the Fed should be wary of doing.

Federal Reserve policy during the Great Recession was not perfect. The Fed was too willing to see green shoots around every corner and that often delayed necessary policy measures, and it was too wary about inflation. But for the most part, and especially when compared to fiscal policy, the Fed’s actions made a big difference and helped the economy recover. As the next chapter unfolds, let’s hope the Fed continues its independent and creative policy actions in response whatever it might face.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: