When the Great Recession hit and it became clear that monetary policy alone would not be enough to prevent a severe, prolonged downturn, fiscal policy measures – a combination of tax cuts and new spending – were used to try to limit the damage to the economy. Unfortunately, macroeconomic research on fiscal policy was all but absent from the macroeconomics literature and, for the most part, policymakers were operating in the dark, basing decisions on what they believed to be true rather than on solid theoretical and empirical evidence.

Fiscal policy will be needed again in the future, either in a severe downturn or perhaps to address the problem of growing inequality, and macroeconomists must do a better job of providing the advice that policymakers need to make informed fiscal policy decisions.

Related: How Income Inequality Can Hurt the Economy

Why was there so little attention to fiscal policy issues in the macroeconomics literature prior to the Great Recession? Why didn’t we have any idea, for example, of what government and tax multipliers are at the zero lower bound? Are they near zero as some people claimed, or, as others believed, much, much larger? Are expenditure multipliers bigger than tax multipliers?

Source: The New York Times

Source: The New York Times

There are two reasons for the lack of attention to fiscal policy. First, many prominent macroeconomists – in large part those in control of which questions are considered interesting enough to warrant publication in the best journals – believed that the problem of large financial meltdowns of the type that led to the Great Depression had been solved.

There was no need to study fiscal policy, monetary policy alone would be enough to counter the mild fluctuations associated with the new era known as the Great Moderation (which many macroeconomists believed had been brought about by improvements in monetary policy, i.e. by their own research on these issues). Second, it would be a waste of time to study fiscal policy in any case since ideological differences in Congress prevented fiscal policy measures from being implemented.

Related: The Mobility Myth and Other Income Inequality Surprises

Unlike monetary policy, where there was considerable agreement within the economics profession over its effectiveness, scores and scores of papers on how to conduct monetary policy within modern theoretical frameworks, and little political opposition to the policies needed during a Great Moderation – relatively minor and measured adjustments in interest rates – fiscal policy faced too many hurdles to bother with. Maybe fiscal policy had a role to play in large, depression threatening downturns, but there was no need to worry about those.

But there was reason to worry, and when the Great Recession hit and political roadblocks gave way to the need to do something beyond monetary policy, economists were unprepared to offer the advice on fiscal policy that was needed.

We mustn’t make that mistake again. There has been quite a bit of work on the use of fiscal policy at the zero lower bound in the last few years, and the emerging consensus seems to be that it is a powerful tool, one that was not employed as effectively as it might have been during the Great Recession. Let’s hope that as the years go by, the research on fiscal policy and the knowledge it brings does not, once again, fade away.

Related: What’s the Best Way to Overcome Rising Economic Inequality?

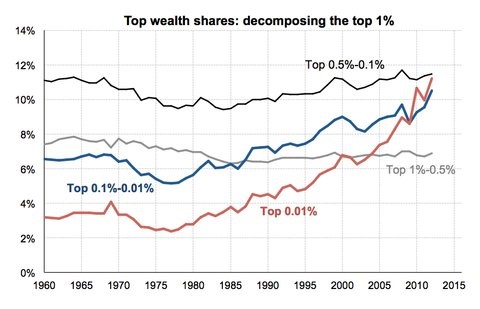

Let’s also hope that political gridlock does not, once again, prevent research into some types of policy. Presently, it would be hard, if not impossible, to implement fiscal policy measures whose sole goal is to bring about a more equitable distribution of income. But politics can change, and if we cannot solve the problem of rising inequality any other way, the day may come when politicians begin to seriously consider the use of tax and transfer schemes to redistribute income.

If and when the day does come, we need to be ready. We know a lot about efficient taxation, but we know much less about “efficient redistribution”. Given the goals of redistribution, what is the best and most efficient way to reach them? There is some progress, e.g. the current research showing that reducing inequality may increase economic growth in many cases, but there is a lot of work to be done. Ideological opposition to the redistribution of income should not stand in the way of research into these issues.

It’s not the job of economists to tell society whether or not they should redistribute income, or if fiscal policy should be used to combat recessions. It’s to inform society of the potential consequences of policy actions, good or bad, and how to best reach particular goals. Too many economists allow their ideological beliefs to color the research they conduct, the advice they give, and the presumed goals of policy.

We need to do a much better job of asking the right questions, and being ready to give judgment-free advice on whatever politicians believe is the best course of action. That’s not to say that economists should never warn that a policy may have large, negative effects on economic growth, employment, etc., – austerity comes to mind – only that policymakers should be made fully aware of the tradeoffs they face when pursuing particular policies.

The question of redistribution is coming, and we need to be ready when it does.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: