Albert Edwards, the global strategist at Societe Generale, has attracted attention as one of the most bearish voices on the market. (“So maybe it’s time to stop dancing and sit this one out,” he just wrote in a new research note.)

With stocks suffering their worst day of the year on Thursday, it’s worth looking at what Edwards sees for the market. He argues that corporate profits could very well be the single most important leading indicator for the economy. Forget job growth. Forget industrial production. Forget durable goods. It's what flows to the bottom line of corporate income statements that matters.

Related: Why Obama’s on Risky Ground in Touting the Economy

That's because profits drive the volatile business investment component of GDP growth, the ultimate swing factor from which things like labor productivity, wages, and hiring flows. When investment dries up, it spells trouble.

But before that happens, profits are pinched.

The consensus thinking is that there is nothing to worry about here. Corporate profits as a share of the economy have been exploding higher. As the Q3 earnings season kicks off, expectations are healthy: S&P 500 earnings are expected to grow 6.4 percent over last year.

This has been driven by a lack of wage growth during this expansion. Since labor costs are the largest expense line on most income statements, profit margins have swelled. American shoppers, squeezed by higher costs and stagnant pay, have turned to debt and asset price inflation to fund expenditures.

This was never going to be sustainable. Now things are starting to change.

Related: Why Hasn’t the Unemployment Rate Fallen in Half the States?

For one, demographics dictated that the skilled labor force was going to dry up as Baby Boomers retired — something that CEOs themselves have warned about — which would tighten the job market and push up wages. Moreover, heavy corporate spending on share buybacks (which I discussed here) has meant businesses have neglected capital investment in new machinery and facilities. No surprise then that productivity growth has been disappointing.

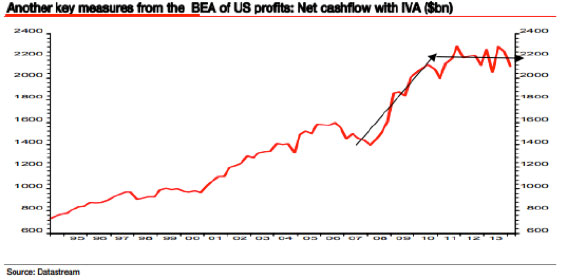

The end result of all this is that one measure of corporate profitability, as shown above, has already begun to roll over.

This is the Bureau of Economic Analysis' preferred measure of whole economy profits, defined as profits from current production that removes inventory profits (an accounting measure). This measure is down nearly 7 percent year-over-year and is falling at a pace not seen since the midst of the financial crisis in 2008.

Edwards focuses on this metric and the ability of shifts in the direction of this metric to lead both stock market measures of profits as well as the business investment cycle.

In his words: "In that sense monitoring whole economy profits can give a good indication of economic vulnerability and predict unexpected recession (of course recessions are always unexpected!)."

The reason that this hasn't shown up in more widely followed measures of stock market profitability, according to Edwards's discussion with officials at the BEA, is that alternate measures of profits are being artificially inflated by the expiration of tax provisions that allowed for accelerated recognition of depreciation expenses, which has resulted in companies expensing less depreciation for tax purposes.

Removing the impact of the dark arts of accounting treatments, the message is clear: Profits are falling. And that means companies have less cash flow available for investment and buybacks, as Edwards shows in the chart above. (You can read more about this from the BEA's press release.)

The overall takeaway is that with profits stealthily on the slide, the U.S. economy is more vulnerable than widely acknowledged to economic slowdowns underway in Europe and across Asia.

German industrial production just dropped at its steepest rate since January 2009. Japan could already have fallen into a new recession. And China is stalling: Economic activity, as measured by the team at Capital Economics, slowed to a five-year low in the third quarter, as electricity production contracted for the first time since early 2009.

Remember that this economic cycle is already getting long in the tooth: At 64 months long, it surpasses the post-war average of 11 economic cycles of 58 months and is well ahead of the 39-month average going back to 1854. (The last three expansions were longer than normal, however, at 73, 120, and 92 months.)

Like a fragile senior citizen, with profits on the slide it won't take much of an adverse shock to do serious damage and increase the risk of a new recession — a fear that's far afield for most investors.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: