The bulls have perpetrated a fantasy over the last few months. It went something like this: You can safely ignore the market declines on foreign bourses and the slowdown of economies in Asia, Europe and the emerging world because the American economy and U.S. stocks were an island of their own.

Thus, as the clouds darkened across the oceans, and despite rollovers in other types of assets from commodities to high-yield corporate bonds, investor confidence remained just short of strip-naked-ebullience. And for good reason: Less than two weeks ago, the large-cap indices like the Dow Jones Industrial Average were tagging record highs.

On Friday, thanks to a strong September jobs report featuring a drop in the unemployment rate to 5.9 percent — a level not seen since the summer of 2008 — stocks were recovering from a bout of selling, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average pressuring the 17,000 threshold once more.

But the skeptics grew nervous. Also for good reason.

Related: Is the Market Bubble About to Burst?

Analysts at Stone McCarthy Research Associates noted that in the week ending September 26, 13 out of 14 global equity benchmarks they cover closed lower by an average of -1.6 percent while the number carrying year-to-date gains dropped from 13 to 9.

Stocks in Brazil started the week off 8 percent from their highs, and those in Italy had fallen nearly as much. Australia was down 6.4 percent, Germany nearly 6 percent, France 4.4 percent, Mexico 4 percent, the U.K. just a bit less, South Korea 3 percent, India 2.7 percent. And Russia is down 24 percent. You can see this in the aggregate in the chart above of the MSCI World Ex USA Index.

In comparison, U.S. stocks were down just 1.8 percent. That looked like it was about to change as the calendar flipped to October. The Dow was slammed below 17,000 as the selling pressure that had done so much damage overseas appeared to wash ashore in America. The Russell 2000 small cap index, which has been underperforming for months, dropped to levels not seen since last November and came within a hair of losing 7 percent on the year.

Where the market goes from here depends on who is right when it comes to decoupling. The optimists or the pessimists? There is justification for both ways of thinking.

Related: Draghi's Lack of Details a Drag for Investors

First, the positives.

Here at home, Macy's (NYSE: M) is seeing enough strength in the consumer to up its seasonal hiring intentions by 3.6 percent this year to 86,000. Kohl's (NYSE: KSS) plans to boost seasonal hiring to 67,000, up from 50,000. No wonder, with consumer spending on durable goods up at an 11.4 percent annual rate in the three months to August.

Overall, U.S. GDP growth has clocked in at a 3 percent annualized rate or more in four of the past five quarters.

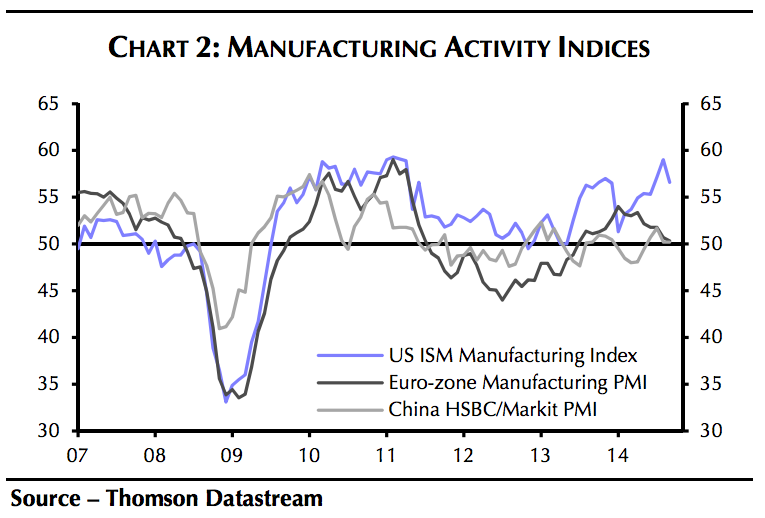

Compare that to what's happening elsewhere. On the economic front, Japanese output disappointed, U.K. home prices dropped 0.2 percent in September for the first loss in 17 months, manufacturing activity in China is dangerously close to stalling, German unemployment rose for the second month in a row as factory activity declined on a month-over-month basis. Deflation continues to threaten the eurozone.

According to the latest global factory activity data, of the 25 countries with the largest economies, 60 percent are seeing growth in factory activity slow. Nine are actually seeing factory activity decline on a month-over-month basis.

Paul Ashworth and Paul Dales at Capital Economics highlight how the U.S. is pulling away from Europe and China in the chart above, but they don't believe it will be a problem. They note that the U.S. economy is fairly closed and benefits from strong domestic demand (explaining Macy's enthusiasm, for instance). If things hold at current levels, they see evidence of U.S. exports to Europe growing by around 5 percent this year while exports to China grow 6 percent to 10 percent.

Maybe so, but they also try to dismiss the impact of a rapid strengthening in the U.S. dollar — something that they even admit the data shows is closely associated with a drop in U.S. exports and a drag on the economy. They also admit that the "risk of an external shock that derails that U.S. recovery can never be fully discounted," although they say they aren't particularly concerned about this happening. The pessimists think otherwise.

Aside from new concerns such as the confirmation of Ebola in the United States, the risk of a tragedy in the streets of Hong Kong as pro-democracy protesters dig in — and other unresolved issues, from ISIS in Iraq and Syria to Ukraine — I recently wrote that the ongoing surge in the U.S. dollar may very well destabilize foreign economies that have been relying on it for fund a massive increase in credit dependence.

In other words, while the American economy may be strong enough to handle a strong dollar (although this is far from clear) the rest of the world may not be able to.

Plus, let’s not forget that weaker foreign economies means American businesses will suffer reduced demand for their goods and services. Just look at the way Ford (NYSE: F) saw its shares pummeled so mercilessly this week after it issued a profit warning based on lower guidance from weaker foreign sales.

Insiders had given up on the decoupling myth months ago. You could see this in the way that most measures of market breadth — or how many stocks are participating to the upside — topped in July and has been narrowing ever since. In fact, while the Dow is less than 2 percent off of its record high, the percentage of stocks on the NYSE above their 50-day moving average has collapsed to just 25 percent, compared to 65 percent at the start of September and nearly 85 percent back in July.

Moreover, this measure of breadth touched a low of just 20.5 percent last week. That's the weakest participation since the current uptrend phase started in late 2012, suggesting that U.S. large-cap stocks — the most widely followed by regular Americans — could be preparing to return to reality, forget the decoupling idea and join global stocks on the downside.

Time will ultimately tell who's right.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: