The news that JPMorgan Chase has reportedly reached a tentative agreement with the U.S. Justice Department to settle civil investigations into the issuance and resale of toxic mortgage securities leaves one big question: Who has the upper hand in the power struggle between Wall Street and Washington at the moment?

Is the $13 billion deal, as The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page suggests, a “shakedown” on the part of the federal government? In some ways. Certainly, the Feds have played hardball in their negotiations with the big bank. They used their ability to file still more costly lawsuits (in ways that would have opened the floodgates for investor and mortgage-holder suits, as well) to extricate more from JPMorgan than the bank ever imagined it would pay.

RELATED: JPMORGAN'S $13 BILLION FINE: WHERE WILL THE MONEY GO?

The House of Dimon, for instance, had first suggested it was willing to fork over $1 billion to settle both criminal and civil charges surrounding the structure and sale of mortgage-backed securities. Government negotiators laughed off that sum. A month ago, it was becoming clear that the bank would face a penalty of at least $11 billion. When JPMorgan Chase set aside an extra $9 billion to cover its legal costs at the end of the third quarter – turning an operating profit into a bottom-line loss – the buzz grew that the sum might be larger still.

Still, it’s not the absolute size of the penalty that has observers agog and critics like the Journal’s Paul Gigot in a tizzy. Rather, it’s the idea of holding JPMorgan Chase accountable for misdeeds that took place at firms it acquired only after those alleged misdeeds occurred. Some of the questionable securities at the heart of the case were sold by JPMorgan Chase itself, but most came from Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual, both of which Dimon's bank absorbed at the height of the financial crisis. Added to that, the critics point out, JPMorgan Chase acquired those banks only on the urging of the Fed and other agencies, at the height of the crisis and with the goal of stabilizing the financial system.

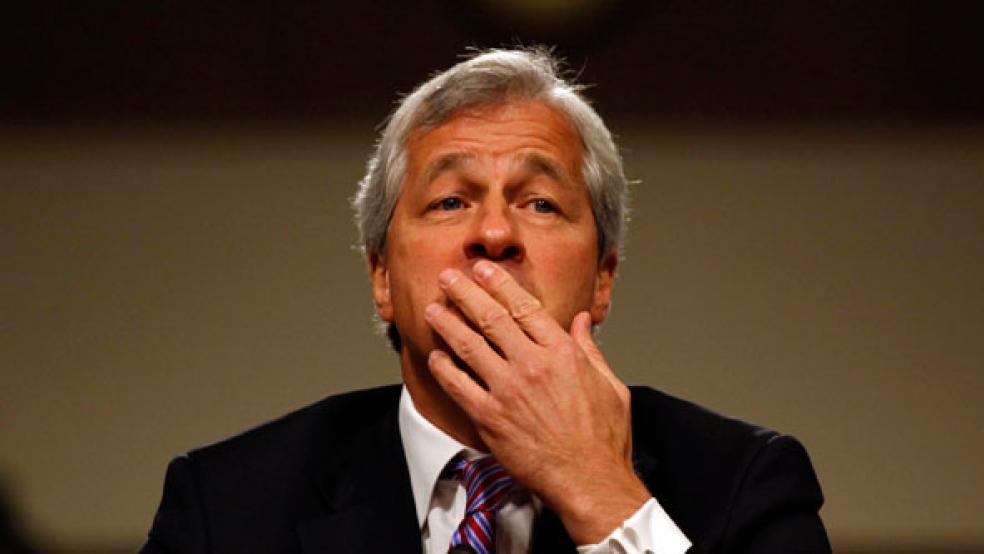

The problem, as Mike Mayo, a veteran banking analyst at CLSA Inc., pointed out, was that JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon trusted the government not to come after the bank with respect to these legacy issues. But they didn’t get it in writing. “What’s the first rule of contract law? Get it in writing,” Mayo said during a Bloomberg Television interview.

Here’s the other side of the story. Sure, the Fed wanted to see these two transactions happen. But it’s hard to argue that Jamie Dimon was averse to the idea of suddenly making his institution the biggest and most powerful firm on the street, rocketing straight to the top of the investment banking league tables. And all at a bargain basement price of $10 a share for a company that only two months earlier had been trading at close to $100 a share. Former Bear Stearns CEO Alan Schwarz compared the deal to being “mugged.”

Similarly, the Washington Mutual transaction, which took place at the height of the crisis in September 2008, vaulted JPMorgan Chase over its competitors and to the top of the list of banks by deposits and assets – a position it hasn’t lost in the years that have elapsed since then. As recently as the previous March, JPMorgan Chase had been willing to invest in the Seattle-based thrift – problems and all – at a price that would have valued it at $9 billion. (JPMorgan Chase didn’t back away; rather, WaMu opted for a capital infusion from a private equity fund.) The bank ended up picking up its battered rival at the bargain basement price of $1.9 billion, problem loans and all.

Yes, JPMorgan Chase was doing the Fed a favor: It was a relatively healthy institution in a position to seize some tremendous opportunities. And to some extent, it was able to cherry-pick its way through the assets.

Jamie Dimon got the Fed to provide some significant guarantees that limited JPMorgan Chase’s risk in the Bear Stearns deal, and the ability to fire any underperforming investment bankers while hanging on to the best of the bunch. Retail banking was a business in which JPMorgan lagged – the bank had essentially no presence in key states like Florida and was itching to go head-to-head with Bank of America in California. JPMorgan Chase’s profits from its retail banking division in the just-ended third quarter are more than ten times what it earned from its retail operations in the third quarter of 2008, before the WaMU acquisition. ‘Nuff said.

Of course, I doubt that Jamie Dimon sees things in quite the same light. But then, as Mayo pointed out, this is the era of “Big Brother banking,” and any banker as astute as Dimon is reputed to be should have been aware of the potential downside. A government that can broker and backstop such gargantuan deals is a government that is likely to play a far more activist role in overseeing and monitoring the banking world going forward.

Wall Street is very familiar indeed with the old saying that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Dimon should have remembered this, and, while he was haggling with the feds, might have thought to demand some indemnity for just this kind of stuff. To the extent that he didn’t, well, that’s a lack of foresight.

This is a timely reminder that there are no real heroes on Wall Street. True, Dimon’s sins tend to be those of omission rather than commission – the flawed oversight of the trading desk that produced the “London Whale” loss being one example. But at the end of the day, JPMorgan shareholders – who have reaped the benefits of the bank’s explosion in size, influence and power in the last five years – are now being asked to pay some of that price for their new status. At the end of the day, the tradeoff may still be a reasonable one.