Is Greg Smith disingenuous? Willfully blind? Machiavellian? Deluded? Peeved by the size of his bonus and feeling vindictive? Or simply stupid?

Whatever the case, the now-former Goldman Sachs banker set both Wall Street and Main Street agog when he quit his job yesterday and, not contenting himself with sending his resignation letter to his bosses, decided he would publish it as an op-ed column in The New York Times. The reason he’s walking away from a job that pays a healthy seven-figure salary and bonus every year aroused even more comment. “The interests of the client continue to be sidelined in the way the firm operates and thinks about making money,” Smith opined.

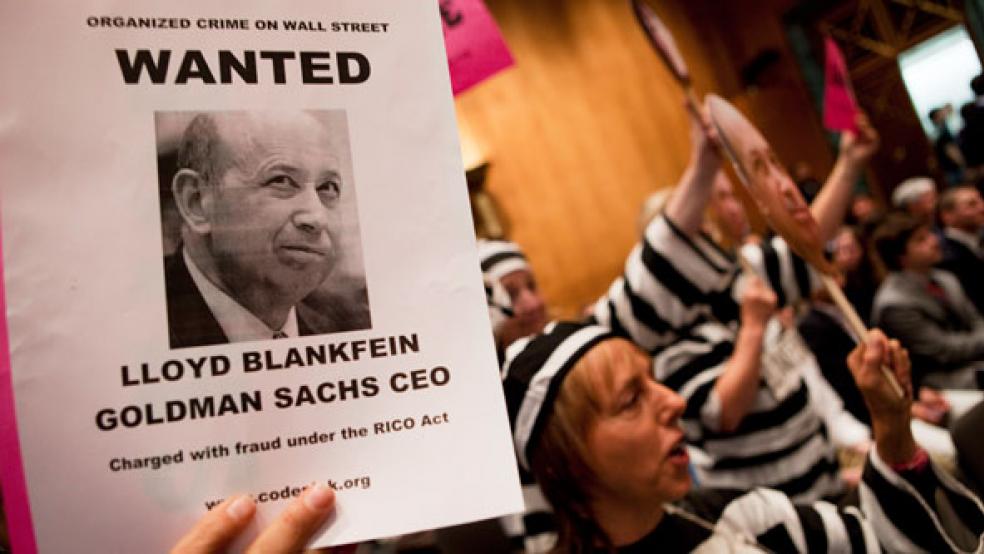

To anyone who followed the Congressional hearings in April 2010, focusing on Goldman’s now-infamous “Abacus” structured transaction, that’s hardly news. Since then, we’ve had years to digest the reality that when a Montana senator demanded of the Goldman Sachs honchos lined up in front of his subcommittee whether they believed they were working for themselves or their clients, Dan Sparks, former head of Goldman’s mortgage business, had to pause before he replied. Even then, the best answer he could come up with was, “that’s a complicated question.”

Smith’s tirade, which easily matches that of Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone that labeled Goldman a “vampire squid,” the answer is simple: yes. His motives for commenting publicly, however, were being analyzed with a growing level of skepticism and even downright cynicism yesterday afternoon. Why, pundits wondered, had Smith ever believed anything different about Wall Street? Why had he been content to swallow his dissatisfaction and disillusion until (so rumor would have it) he received a bonus he believed didn’t reflect his talents or contributions? Weren’t his complaints sheer hypocrisy? Well, possibly.

But the bottom line is that Smith represents a large number of bankers on Wall Street. I talked to a lot of them when researching my book, Chasing Goldman Sachs, first published in the summer of 2010 (and in an updated paperback edition last October.) Many of them would only agree to discuss their concerns about the way the industry and their firms had changed over the last two or three decades if I agreed not to use their real names.

Once I made that promise, scores of current and former bankers just like Smith told me they wanted to do the best for their clients. They loved the big fat paychecks, but they also relished the challenges of finding a clever solution to a client’s corporate finance problem, helping an investment manager unload a big block of stock, or structuring financing for a complex buyout deal. The folks who created credit derivatives were exhilarated not by the fat bonuses, the promotions or the chance to make money off clients, but by the rare opportunity to create a genuinely new financial instrument that would enable users to keep lending to long-term clients while diversifying their credit exposure.

The Smiths of Wall Street stick around as long as they do because they hope they can keep doing interesting work. For every banker who scornfully refers to clients as “muppets,” others try to serve the client and maintain a good relationship. That’s hard in today’s Wall Street, however. As one former very senior Goldman Sachs official told me, the firm’s culture began to change at about the same time that Smith joined the company back in 2000, in the wake of its IPO.

“We had gone from being a firm that saw a value in principles to one that saw the greatest value in earning the fattest fee possible,” he said. Sure, there was greed. As he described it, this was “long-term greed” – the desire to make as much as possible by building a sustainable business, not by maximizing what the bank could make off its clients and paying little heed to whether the deals being done were “win win.”

That individual – who still declines to let me use his name publicly – left Goldman several years ago, and says while he has great memories of working there, he was glad he left when he did. The “good Goldman,” he says, had been able to turn away deals and potential clients or counterparties it didn’t want to do business with.

The new Goldman, in the wake of its IPO and under pressure to maintain a high return on equity, could not afford to turn anything away. That, he said, was why transactions like the Abacus arrangement – in which hedge fund manager John Paulson helped decide which mortgage securities would be packaged in a portfolio that he’d bet against, the other side of which Goldman sold to clients without disclosing Paulson’s role.

The bottom line is that Wall Street needs to strike a balance between the pursuit of profits at all costs, and the need to act in the best interests of its clients and counterparties. Yes, it’s harder to do business in the post Dodd-Frank era on Wall Street, but in large part that’s because of the Street’s own cavalier approach.

Every time a banker serves himself first, then his clients and the interests of the financial system, there’s more public outrage and even more pressure for still more aggressive regulation that will make it still harder for the likes of Goldman Sachs to earn a decent return on equity. Cobbling together deals that your own bankers are willing to describe as “shitty” is about as rational as slathering lead-based paint over the toys you manufacture and then handing them out to toddlers. It’s going to come back and bite you.

Greg Smith is courageous. He speaks for many on Wall Street who are unwilling to walk away from a healthy paycheck, much less render what they and their closest friends have been doing meaningless by publicly declaring that the Emperor has no clothes. That takes courage. Many of those friends will never talk to him again and Goldman Sachs will probably sue him for defamation or for breaching confidentiality clauses in his employment contract. I would not be as quick to conclude he’ll never work on Wall Street again.

Smaller firms might be happy to snap him up as proof that their businesses are ethical and above reproach in contrast with the evil vampire squid. Smith may be a hypocrite or naïve to imagine that today’s Wall Street could be any different than it is. But by making his resignation so public, he is pouring scorn on the claim by Goldman Sachs that it has overhauled its business practices, a pledge it made as a de facto part of its settlement of the charges levied by the SEC in connection with the Abacus transaction.

For his comments to be taken seriously, however, Smith needs to go further. He needs to answer whether he thinks it’s realistic to expect anything better from Goldman or the rest of Wall Street (which is, make no mistake, just as culpable). And, if so, what needs to happen next -- what’s the solution? He has our attention…we’re waiting.