Every day, 130 million Americans report for work. Every day, on average, 12 do not return home because they were killed on the job.

Saturday was Workers Memorial Day and federal officials in charge of the agencies responsible for workplace safety solemnly noted the continuing toll on U.S. workers, 4,690 of whom died from on-the-job injuries in 2010, three percent more than the year before. “This is intolerable,” said David Michaels, administrator of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. “Making a living shouldn’t include dying.”

“These losses of lives and livelihoods cost our economy at least $250 billion annually,” said John Howard, director of the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. “The associated toll in human suffering is impossible to calculate or repay.”

It’s normal on such occasions for the media to make at least a passing nod toward an issue that is usually ignored unless some horrific disaster happens, such as Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch mine explosion that killed 29 miners in West Virginia two years ago. But this past weekend, the national press contained nary a story about job safety. A search for “Workers Memorial Day” on Google News found a few local news reports about commemorative events in communities devastated by recent disasters.

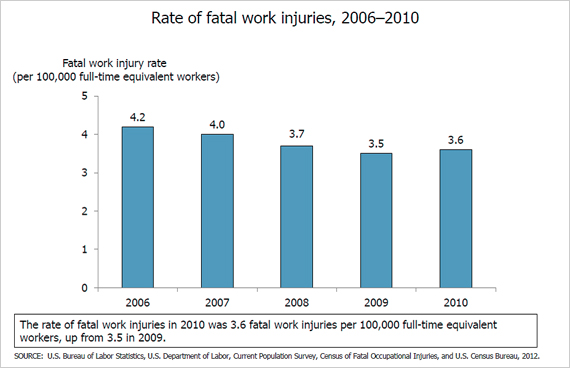

It’s too bad because even a cursory review of the statistics shows that progress in reducing workplace fatalities came to a crashing halt in the 2000s. After making slow but steady progress for most of OSHA’s first 30 years, workplace fatalities rose every year during the economic expansion that took place between 2002 and 2007 and were 5.5 percent higher at the end of the period.

That was very different experience than during the Clinton-era expansion of the 1990s when workplace fatalities dropped almost every year. Between 1994 and 2000, workplace fatalities fell 10.7 percent.

It should be noted that the world has changed considerably since the Occupational Safety and Health Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1970. Manufacturing employment has fallen from one in every four private sector jobs to one in every ten. Construction sites are safer as are most mines. In 1970, over 13,000 workers lost their lives on the job each year. Today, it’s a third that level with a much larger workforce.

There was a sharp falloff in workplace deaths in 2008 and 2009. But that was largely due to the recession. When fewer people are working, fewer people die on the job. That especially true when relatively more dangerous occupations like construction, transportation and manufacturing are taking the biggest hits in employment.

But the uptick in 2010 as the economy began to improve suggests that the pattern of the 2000s may be repeating itself. A review of the regulatory landscape reveals why that should come as no surprise.

Business lobbyists during the Obama years have succeeded in grinding the regulatory process at OSHA and other agencies to a halt. When the Republican-controlled Congress held a hearing last year on regulatory overreach at OSHA, the lawyer testifying for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce was left complaining about a noise abatement rule that had already been withdrawn. It and other business lobbying groups also postponed consideration of a recordkeeping rule that would have required employers to keep track of workplace-related musculoskeletal disorders like carpal tunnel syndrome, which now go uncounted.

These were not isolated instances. The pro-regulation group Public Citizen in a report issued last fall reviewed the past ten year’s record at OSHA compared to prior decades. It found between 2001 and 2010 (including the first two years of the Obama administration), OSHA produced just one new workplace health and safety standard every 2.5 years. In the prior three decades, the agency produced 2.6 rules per year.

“The requirements on OSHA (to get a rule passed) have nearly paralyzed the agency,” said Justin Feldman, who authored the report for Public Citizen. “As a result, OSHA cannot adequately protect workers from toxic chemicals, heat stress, repetitive use injuries, workplace violence and many other occupational dangers.”

Still, don’t expect that to interfere with the rhetoric that will pour from television ads backing Republican presumptive nominee Mitt Romney this fall. He blames the economy’s poor performance under Obama in part on the excessive regulations imposed by agencies like OSHA and the EPA.

“One of the greatest problems with the federal bureaucracy is that each incoming presidential administration leaves in place much of what its predecessor constructed. The result is layer upon layer of often unnecessary or inconsistent regulation,” the candidate says on his website. “President Obama has compounded this problem with unprecedented federal power grabs over wide swaths of the economy.”

There probably are many rules on OSHA’s books that no longer apply in a post-industrial economy. If misguided OSHA inspectors are wasting their time by enforcing them, they should be reined in.

The reality is that the agency’s budget has been stagnant for years. Even if one includes the state agencies that enforce federal rules, there are just 2,200 inspectors for 8 million American worksites. Only one in 87 were inspected last year. That’s not even enough people to stop the workplace death toll from rising, much less engage in a “power grab.”