As president of the Collegiate Veterans Association at Florida State University, Abby Kinch often heard from veterans who ran into a stumbling block before they even started their college careers.

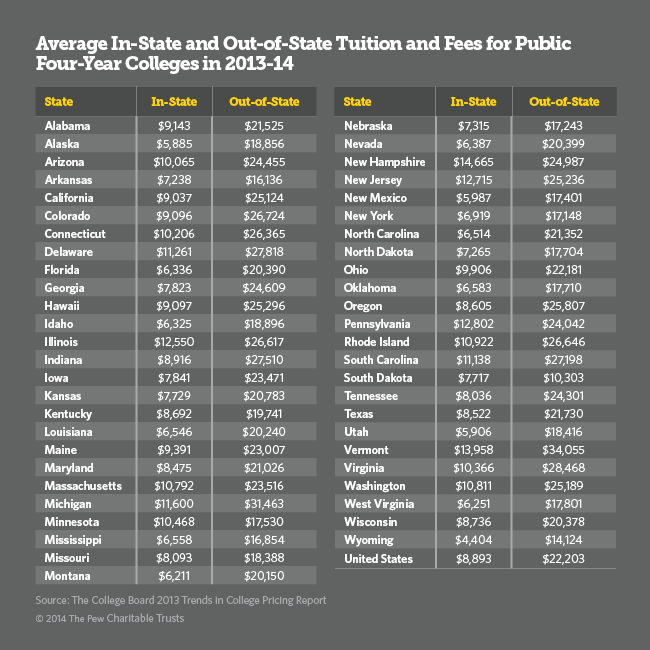

Veterans new to the state who enrolled at Florida State soon discovered they had to pay out-of-state tuition for their first year, or an additional $15,000. (By the second year, they had lived in the state long enough to have established residency.) For some, that meant the difference between attending college or not. For many others, it meant the burden of student loans they hadn’t planned on.

In May, however, Florida joined a growing list of states that have made it easier for veterans to qualify for in-state tuition. And starting next year, recent veterans in every state should be able take advantage of in-state tuition rates, thanks to a little-publicized provision in a $16 billion federal law signed by President Barack Obama earlier this month.

Related: Walmart Hiring 100,000 Vets: Smart Move or Cynical Ploy?

Aimed primarily at improving veterans’ access to health care, the law allows any veteran who has served at least 90 days of active service to pay resident tuition rates in any state within three years of leaving the military. The law also covers spouses and dependent children of veterans meeting certain criteria. Effective July 1, 2015, the law would apply to any public college or university receiving federal funding through the Post-9/11 GI Bill.

In 2013-14, the average in-state published tuition and fees at public colleges was $8,893, compared to $22,203 at out-of-state colleges, according to the College Board.

“I think that because student veterans spent their careers defending the United States, it’s important to welcome them back to the United States with an education wherever they would like to study, not just in their home of record,” said Kinch, who spent more than two years working for the passage of the Florida legislation.

Veterans and veterans’ advocates applaud the measure, which will help alleviate the problem of veterans failing to qualify for in-state tuition after leaving the military because they have been required to move for their service. But others wonder what the change will cost state colleges and universities, and what the impact might be on tuition or services, which may be impossible to know until veterans start taking advantage of the new law.

States Take the Lead

More than one million people have attended college with the help of the Post-9/11 GI Bill, which covers most in-state tuition costs and fees in a veteran’s state of residency. In the next few years, another 1.5 million veterans will be discharged from the military, and about one third are expected to use GI Bill to attend college, according to Wayne Robinson, president of Student Veterans of America, a nonprofit coalition of student veterans groups on college campuses.

Suzanne Hultin, a policy specialist with the National Conference of State Legislatures, said at least 32 states already offer veterans resident tuition rates. Many states have adopted legislation in recent years. In some states, such as Alaska and Georgia, public university systems have created such policies.

Related: This Army Vet Says the Government Is Overpaying Him

The rules vary across states. Some require veterans to declare or establish residency, some cover only veterans who have been honorably discharged and some call for veterans to live within the state throughout their enrollment in college, for example. Rules for spouses and dependents also differ across state lines.

(States have also tried to help veterans receive academic credit for their military training and service.)

Washington was among the states that enacted legislation this year to remove a waiting period for veterans to be eligible to pay resident tuition. The state is home to the largest naval station on the west coast, on Whidbey Island, as well as Joint Base Lewis-McChord, which joins the Army’s Fort Lewis and the Air Force’s McChord Air Force Base.

“I hope that we will keep our veterans and their families when they separate from the military here,” said state Sen. Barbara Bailey, the Republican who sponsored the legislation. “They are great members of our communities.”

In North Carolina, Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican, this year proposed a $5 million scholarship fund for the state university system to cover the gap between in-state and out-of-state tuition for veterans, as well as a waiver granting veterans in-state tuition rates for community colleges. The legislature ultimately approved $5.8 million for public colleges and universities, including community colleges, to participate in the federal Yellow Ribbon Program, which provides schools matching federal funds to cover part of the gap between in-state tuition and out-of-state tuition or tuition at a private institution.

Jon Young, provost and vice chancellor for academic affairs at North Carolina’s Fayetteville State University, where about one in five students are affiliated with the military, welcomed the federal legislation. Young said it would help to clarify some of the confusion about when veterans and their spouses and dependent children become eligible for in-state tuition, which is about $10,000 less per year than out-of-state tuition.

But Rep. Rick Glazier, a Democrat from Fayetteville, worried about what new federal law would cost, particularly in light of several years of reductions in state aid to higher education.

“I am concerned that this is an incredibly important and good program, but it has costs, and between the federal and state governments, no one right now will be picking up those costs so it will be essentially forced on the universities,” said Glazier, who also teaches criminal justice at Fayetteville State University. Glazier said unless the state or federal government provides additional funding to cover the difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition, students could see tuition hikes, cuts in services or both.

What Will It Cost?

In a June letter to Congress, the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities expressed deep concern that the federal legislation would mean the loss of Yellow-Ribbon educational benefits paid to public universities, while private colleges, including for-profit institutions, would continue to receive these funds.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the new law would save the federal government $175 million in Yellow Ribbon Benefits from 2015 to 2024.

Related: Obama Targets a Twofer to Lead the VA: A Vet and a Former CEO

The association also asked that the legislation be pared back to cover only veterans and not their spouses or dependent children and urged Congress to consider that state governments have historically determined their own residency requirements for in-state tuition rates.

Beyond the loss of the Yellow Ribbon benefits, no one knows yet how much the federal law will cost public colleges and universities in lost tuition.

Makese Motley, assistant director of federal relations for the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, said that while the association does have questions and concerns about implementation and costs, the group believes that the outcome “needed to happen.”

“We owe it to our veterans,” Motley said. “We have a lot of veterans coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan. We’re seeing them show up on our campuses and we want to give them the support that they deserve.”

This article originally appeared in Stateline, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.