In late 2012, Harry A. Croft, a psychiatrist and former Army doctor who specializes in veterans’ post-traumatic syndrome disorders, was approached by a human resources specialist for a Fortune 500 company. Croft had just delivered a speech in New York City promoting his new book on the problems of veterans readjusting to civilian life.

At the time, many post-Sept. 11 era military veterans were struggling to find work, and one of the reasons was employers’ fears of hiring anyone with PTSD.

“She looked at me seriously and said, ‘Look Doc, here’s my worry with this PTSD deal,’” Croft recalled in an interview on Monday. “’Do you think the other employees are going to catch it?’ And I kind of chuckled inside and said, ‘Well, just keep them off the toilet seats.’”

Related: Will Guns and Therapy Stop Military Base Killings?

“But it went straight over her head,” Croft added. “I didn’t anticipate that degree of misunderstanding and stigma about it in the workplace. That was my eye-opener.”

Croft, who practices in San Antonio, Texas, strongly asserts what some industry studies have documented over the years: that while many companies believe that hiring returning veterans is good for business and patriotic to boot, they fear they would be taking huge risks by disrupting their workplace or worse by recruiting and hiring post-911 veterans.

“PTSD is the big giant elephant in the boardroom that a lot of people worry about but nobody talks about,” Croft explained. “Are they [veterans] going to shoot up the workplace? Are they going to be disruptive?”

That concern assumed greater urgency last week after a solider with a history of mental illness went on a rampage at Fort Hood, Texas, killing three people and wounding 16 others with a .45-caliber Smith & Wesson semi-automatic pistol before he took own life. The shooter, Spec. Ivan Antonio Lopez, a 34-year-old military truck driver and Iraq veteran, had been taking medication for anxiety and depression, but he wasn’t viewed by doctors or his superiors as a threat.

The shooting was the third major gun attack at a U.S. military installation in five years. While it rekindled a national debate over the need for better security at military bases and the efficacy of the treatment of mental disorders among veterans who had had been deployed to war zones, it could also make businessmen think twice before filling openings with vets.

“The problem is, when these events take place . . . it just increases that stigma to the point that many businesses who were seriously thinking about hiring vets change their mind,” insisted Croft, author of I Always Sit with My Back to the Wall, which focuses on the problems of PSTD.

Related: Military Gateway to the Middle Class Is Vanishing

“The events at Fort Hood were tragic, and our thoughts and prayers remain with the military families and community members affected by this shooting,” said Jennifer Giering, director of business and state engagement for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation’s “Hiring our Heroes” program.

While declining to speculate directly on the possible impact of the shootings on future employer decision making, Giering said, “We realize at this point that we can’t let our foot off the gas” in promoting veteran job creation and placement.

Mike Mullen, the former chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, urged employers and other decision makers not to hold veterans responsible for the terrible acts of a few.

“This is a great military, and I wouldn’t want one incident like this to tarnish the reputations of the hundreds of thousands of vets in our country who run businesses, who teach at schools, who coach little league games and who make a big difference in our community now and will for the future,” he said Sunday on NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

A 2010 study by the Society for Human Resource Management on recruiting and employing military personnel found that 46 percent of the employers cited PTSD and related mental health issues as a potential deterrent to their hiring veterans.

Related: America’s Vets: More Jobs, More Help, More Suicides

A subsequent study by the Center for a New American Security on business leaders found that scores of companies thought it would be highly beneficial to employ veterans because of their leadership and teamwork skills, character and discipline.

Yet 58 percent of company representatives interviewed thought it would be a problem for other companies to hire veterans of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq because of “negative stereotypes.”

The companies surveyed included the cream of the business world, such as AT&T, Bank of America Corporation, General Electric, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Lockheed Martin, Merck & Co. and Wal-Mart.

PTSD is a mental disorder that typically develops after a person experiences a terrifying ordeal that involves physical harm or the threat of physical harm. It is most closely associated with veterans who have seen combat or were deployed in war zones, but it can result from a variety of other traumatic incidents, such as a mugging or rape. While experts say there are numerous symptoms, the most common from an employer’s perspective are irritability, inflexibility and a tendency to fly off the handle.

“Some employers report concerns about the effects of combat stress, including post-traumatic stress issues, anger management and tendencies toward violence,” according to the Center for a New American Security study. “Additionally, whereas some companies intentionally recruit veterans because of their perceived comfort with structure and discipline, other companies speak negatively of veterans’ rigidity.”

Related: Painful but Necessary Military Cuts Draw Fire from Vets

Margaret C. Harrell, a senior social scientist with the RAND Corp. who co-authored the 2012 New American Security study, said last week, “I think employers that already have veterans amongst their ranks recognize that they’re valuable, capable employees.”

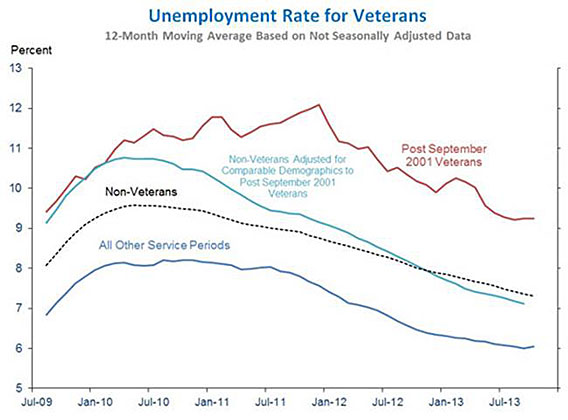

Historically, veteran unemployment lagged behind the national average, but it was higher for the younger, post-911 vets – many of whom returned from war with grievous injuries or mental health issues.

The unemployment rate among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans was about two percentage points higher than that of their civilian peers in 2013, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But some experts believe the gap isn’t even that large.

When one examines post 911 veterans by education and by age, according to Harrell, the older they are and the more education they have, the better they fair.

Two years ago, President Obama announced a challenge to the private sector to hire or train 100,000 unemployed veterans or their spouses by the end of 2013. The impulse to recruit and place veterans led corporate America to make some massive promises, The Washington Post reported last week.

Related: Young Military Vets Face New Battle for Jobs

The Chamber of Commerce’s “Hiring Our Heroes” program has collected pledges from businesses to hire 411,000 veterans and military spouses on its way to a goal of 500,000. Wal-Mart has said it plans to hire 100,000 veterans. Home Depot has pledged 55,000, McDonald’s 100,000 and Starbucks 10,000 more.

What’s puzzling, however, is that even with this massive outpouring of concern and effort – with pledges totaling more than one million jobs – there are still 210,000 unemployed post-Sept. 11-era veterans looking for work.

“The math is overwhelming,” The Post reported. “There are now about five pledged jobs for every unemployed service member who fought in Iraq or Afghanistan.”

One possibility is that some of these corporate programs have trouble keeping tabs on job pledges, which may lead to double counting, according to one expert on veteran employment issues. Whatever the problem, the Chamber of Commerce Foundation says that the overall effort has been highly successful.

“When Hiring Our Heroes started, post-9/11 veterans faced a rate of roughly 12 percent unemployment, and veterans under 25 faced a rate closer to 30 percent,” said Giering. “Those numbers have improved, and part of that improvement can be attributed to the collective actions of private, public, and nonprofit groups working together to address the issue.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: