The director of President Obama’s National Economic Council on yesterday continued the administration’s public criticism of the Congressional Budget Office on Thursday, arguing in an interview with Politico chief economics correspondent Ben White that the neutral agency’s analysis of a plan to raise the minimum wage was flawed.

Careful to be polite, and to note that public disagreement is a healthy part of the policy process, NEC Director Gene Sperling was, nonetheless, adamant that the CBO had simply got it wrong when it projected that the administration’s proposal to increase the minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 by 2016 would cost the economy half a million jobs, even as it raised the wages of as many as 24 million workers.

Related: CBO Finds Minimum Wage Research “Biased”

The primary argument between the two sides is over what economists refer to as the “elasticity” of the employment rate in the face of changes to the minimum wage – that is, how sensitive the employment rate is to changes in the wages of the very lowest-paid workers.

The CBO studied the literature and, based on various studies done by economists in the past few decades, determined that the employment rate is moderately responsive to the wage rate. It’s an intuitively pleasing result, Sperling admitted, because basic economics says that as the price of something increases, demand for it will fall.

However, he added, “The best economic research is not the research that puts in an automatic elasticity,” said Sperling, “It’s what looks at actual human behavior.”

As it turns out, numerous studies looking at “natural experiments” in minimum wage increases – meaning actual events rather than academic models – find that moderate increases have “no discernible effect” on employment.

Related: CBO – Minimum Wage Hike Would Cost 500,000 Jobs

The first evidence that this might be the case arose in 1994, when economists David Card and Alan Krueger published a paper studying employment at fast food restaurants in neighboring parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey after New Jersey raised its minimum wage and Pennsylvania kept its wage steady. The economists surveyed hundreds of restaurants on both sides of the border, and determined that the wage hike in New Jersey had no measurable effect on employment.

Since then, according to Doug Hall, director of the Economic Analysis and Research Network at the Economic Policy Institute, other economists have done similar studies at the state and county level when a minimum wage change makes labor more expensive in one jurisdiction than in a neighboring one.

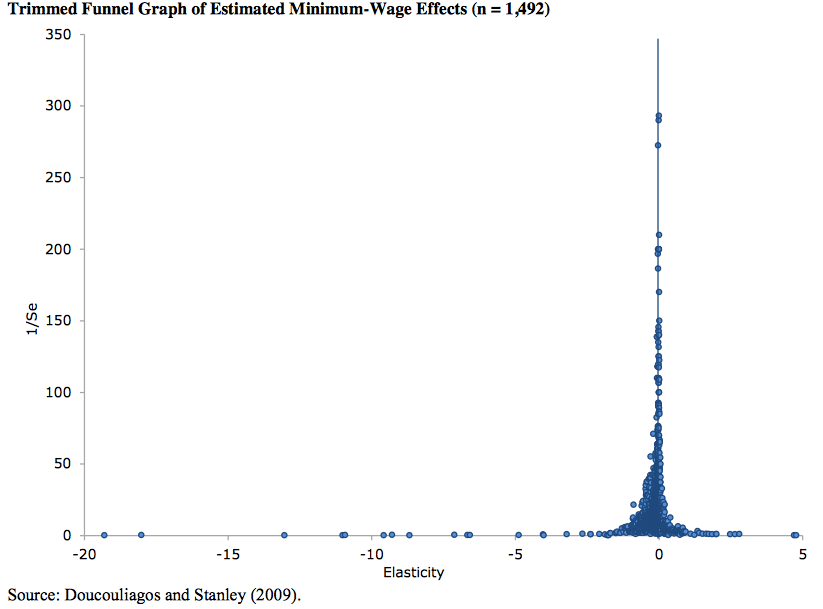

The chart above shows the results of more than 1,400 different studies. The x-axis shows the size of the employment effect, and the y-axis shows that statistical power of the analysis.

The results have clustered around the finding that a moderate wage increase – in line with the administration’s proposal to increase the minimum rate in 95-cent increments – has zero effect on total employment. And the higher a study’s statistical power, the more likely it is to fall on the line showing zero effect.

“I really think that’s a very compelling takeaway,” said Hall, who has testified before multiple state legislatures on the issue. “It puts the lie to the notion that it’s going to be a tremendous job killer.”

Related: White House Attacks CBO Over Minimum Wage Report

Regardless of any academic consensus, it still appears highly unlikely that the administration will be able to push a minimum wage increase through Congress, as Republicans in control of the House of Representatives, have united behind the CBO finding that such a move would cost jobs.

A recent editorial in the conservative National Review had this takeaway from the CBO finding:

“The logical extension of this insight is not to lower the minimum wage, but to abolish it. The federal minimum wage is merely a statutory floor; the real minimum wage, which already is collected by our millions upon millions of unemployed and will be collected by a half-million more should the Democrats get their way, is $0.00. That’s what unemployment pays.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: