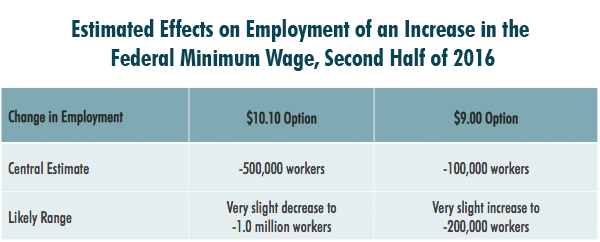

The White House attacked the Congressional Budget Office on Tuesday after the CBO released a report suggesting that raising the minimum wage would likely cost the economy half a million jobs, even as it raised the wages of 16.5 million workers. The administration’s chief complaint was that the CBO had failed to take into account the findings from “recent economics literature.”

Ironically, according to an appendix to the report, not only did CBO researchers look at the economic research, they also decided that it was biased and revised their estimates accordingly, in a way favorable to the White House’s position.

Related: White House Attacks CBO Over Minimum Wage Report

“According to some analyses of the minimum-wage literature, an unexpectedly large number of studies report a negative effect on employment with a degree of precision just above conventional thresholds for publication,” CBO analysts write. “That would suggest that journals’ failure to publish studies finding weak effects of minimum-wage changes on employment may have led to a published literature skewed toward stronger effects. CBO therefore located its range of plausible elasticities slightly closer to zero—that is, indicating a weaker effect on employment—than it would have otherwise.”

Translated into English, this means that the CBO believes that economics journals are biased toward publishing papers that present evidence that minimum wage increases hurt employment, and are less likely to publish papers that show a weak effect – or no effect at all. So, when CBO analysts came up with their estimate of how big an effect a minimum wage hike would have on employment, they settled on a smaller impact than they believed economic literature would support.

In support of their decision, CBO analysts included a link to a paper by economists Hristos Doucouliagos and T. D. Stanley finding that, taken as a whole, “the minimum wage effects literature is contaminated by publication selection bias.”

Related: CBO – Minimum Wage Hike Would Cost $500,000 Jobs

So if the economic literature on the minimum wage is unreliable, what does that say about the economic literature that informs policymakers’ choices in other areas of research, such as trade policy, unemployment benefits, and immigration, to name a few?

“As an economist, I hate to say this, but it’s a real problem,” said Leonard Burman, director of the Tax Policy Center in Washington and a professor of Public Policy at Syracuse University.

Because there are significant professional rewards associated with frequent publication, and because economists can mine data and refine models until they produce a suitably counterintuitive result, Burman said, much of the academic literature in economics may well be skewed toward papers that purport to invalidate accepted theories, while those that replicate another researcher’s findings never get put into print.

It’s a point that other economists have made in the past, and it marks a distinct difference between economics and the hard sciences, where research replicating others’ results is not just valued, but is considered vital to the advancement of knowledge.

“Nobody wants to publish the conventional wisdom,” said Burman. Not even, it seems, if it happens to be correct.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: