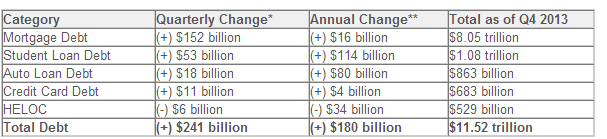

Americans piled on debt at the end of last year, in the surest sign yet that the great belt-tightening prompted by the Great Recession has reached a turning point. U.S. household debt grew by $241 billion, or 2.1 percent, in the last three months of 2013, as consumers borrowed more to buy homes and cars, added to their credit card balances and took out loans to pay for college.

The added borrowing represents the largest quarter-to-quarter jump since the third quarter of 2007, before the recession took hold, according to data released Tuesday by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The demonstration of consumer confidence could mean brighter days ahead for the economy.

Related: How Keynes Would Handle an Abnormally Slow Recovery

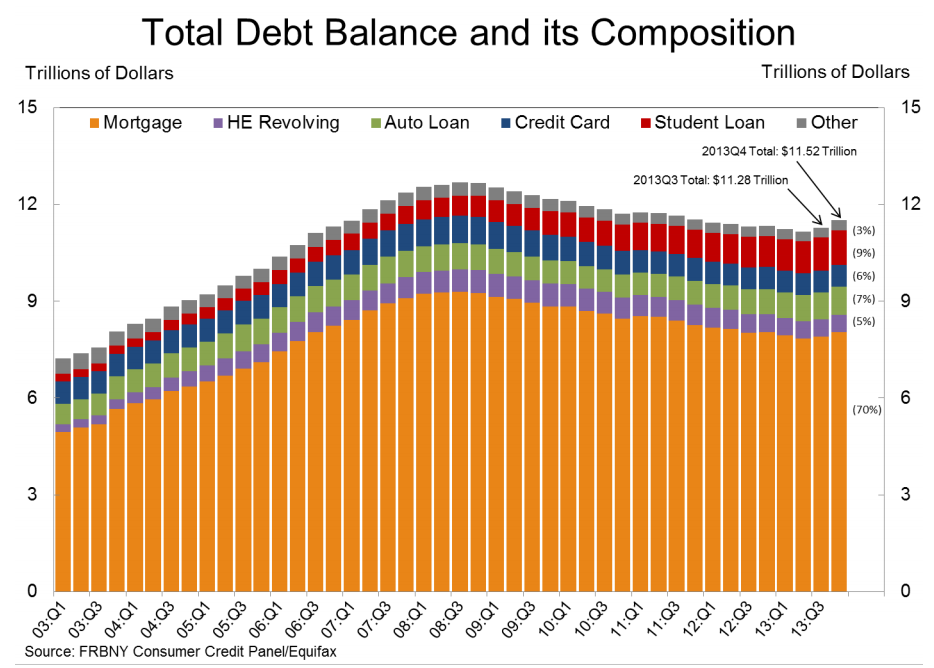

Total consumer debt, including mortgages, credit cards, student loans and car loans, climbed from $11.28 trillion to $11.52 trillion over the fourth quarter of 2013. Borrowers are also showing that they can handle the increased balances, as overall delinquency rates continued to drop. As of the end of 2013, 7.1 percent of outstanding debt was in some stage of delinquency, down from 7.4 percent at the end of the third quarter.

Mortgages, which account for most household debt, grew by $152 billion from third-quarter levels and $16 billion from the end of 2012, ending a four-year stretch of annual declines. Student loan balances swelled by $114 billion last year, reaching a total of $1.08 trillion.

Throughout all of 2013, total household debt grew by $180 billion (1.6 percent). That marks the first four-quarter stretch since late 2008 to register an increase. “This quarter is the first time since before the Great Recession that household debt has increased over its year-ago levels, suggesting that after a long period of deleveraging, households are borrowing again,” said Wilbert van der Klaauw, senior vice president and economist at the New York Fed.

As the chart below shows, debt levels may have reached an inflection point in the third quarter of 2013, yet overall debt balances remain 9.1 percent below their $12.68 trillion peak from the third quarter of 2008. Economists at the New York Fed also noted that, with the exception of auto loans and student loans, “overall growth in debt remains considerably more muted in 2013 than it was in 2006.”

So who’s behind all the new borrowing? “The Young and the Riskless!” van der Klaauw and other New York Fed economists wrote in a blog post. The data show that, unsurprisingly, “balance increases were mainly driven by younger age groups.” Borrowers with higher credit scores account for increases in mortgage and credit card balances.

On the other hand, the rise in student debt has been driven to a large extent by borrowers with relatively weak credit scores of 680 or lower — and delinquency rates for student loan debt remains high. About 11.5 percent of student loan balances were at least 90 days delinquent or in default as of the end of 2013, down from 11.8 percent in the third quarter but up sharply from five and ten years ago.

Related: 5 Ways to Manage Student Debt (And Still Pay Your Rent)

It’s not surprising that borrowers with worse credit are racking up educational debt, as many students have extremely short credit histories and haven’t yet built up their scores. Many of those students could go on to get jobs that pay better than jobs they could have landed with just a high-school degree.

At the same time, the data might suggest that the burden of student loan debt is making it harder for many young borrowers to start their financial lives and qualify for loans to help them buy homes and cars. Home sales to first-time buyers remain depressed, The Washington Post reported yesterday — and housing experts say student debt is partly to blame.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: