Congressional budget talks may be winding their way to a narrow agreement on 2014 spending levels, but before the results of those negotiations are announced, there are a couple of reasons to reopen the books on fiscal 2013.

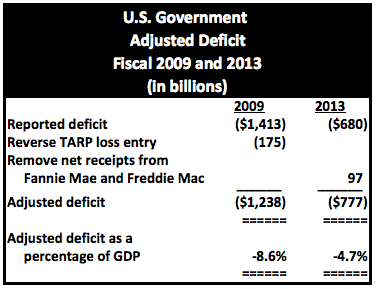

When the Obama administration issued its final Monthly Treasury Statement of fiscal 2013, delayed by the partial government shutdown on October 30, it claimed the federal government's reported deficit of $680 billion, expressed as a percentage of the nation's gross domestic product, was less than half of what it was four years ago.

That claim is itself shaky, as we’ll see below. The joint statement issued by U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew and Office of Management and Budget Director Sylvia Burwell went further, trumpeting how the result — the first annual deficit of less than $1 trillion since 2008 — represented "a reduction of more than half from the deficit that the Administration inherited when the President took office in 2009."

On its face, the numbers meet the administration’s claims, but digging into the accounting suggests that real progress on the deficit has been less dramatic than Lew claimed.

Related: Federal Budget: 10 Cuts That Would Save the Most

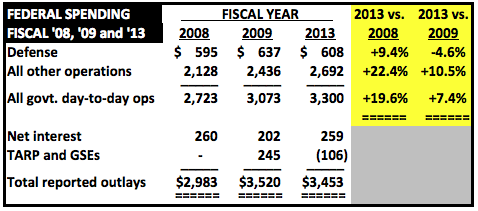

Even as Team Obama complains about what it "inherited," it fails to acknowledge that it artificially stuffed over $170 billion in phantom paper losses into fiscal 2009, and that it substantially and unsustainably raised the federal spending baseline for virtually everything except national defense during the next four fiscal years.

The phantom losses were booked in April 2009, when Treasury made significant adjustments to that month's statement, revising all previous months back to October 2008, the first month of the 2009 fiscal year.

Until March of 2009, the government had treated TARP monies lent or invested in financial institutions and other entities as direct outlays. In April, it retroactively began accounting for those amounts, totaling over $350 billion, as investments.

Accounting for TARP as a collection of investments separate from the day-to-day operations of the rest of the government was a defensible move. What was not proper was Treasury's arbitrary decision at the same time to record an estimated loss of $178.2 billion on those investments as an additional government "outlay."

Since outlays are supposed to represent disbursements of cash, the unrealized TARP loss was not an "outlay" in any real sense. This non-cash accounting entry served a useful administration purpose, namely to push as much "bad news" as possible into fiscal 2009 so that subsequent years might look better.

What's more, Treasury almost certainly knew that its TARP investment losses would be nowhere near the amount it had artificially added to outlays before it closed the books on fiscal 2009. Its Office of Financial Stability formally acknowledged in early December 2009 that it had sharply revised estimated TARP losses downward to just $41.6 billion. They apparently felt that it was too late to go back and change already-recorded results.

Given that the recession had officially ended in June, it's reasonable to believe that Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner knew of this substantial improvement before his department issued fiscal 2009's final Monthly Treasury Statement on October 16. If so, he should have made sure to take back most of the original reduction. Instead, Treasury waited until March 2010's Monthly Statement to reduce them by $115 billion. It was a nice way to make fiscal 2010 look marginally better than 2009, when it really wasn't.

As of October 31 of this year, Treasury anticipated overall TARP Investment Program losses of less than $3 billion, indicating that its guessing game four years ago was a complete waste of time at best, and deliberate accounting trickery at worst.

As the Congressional Budget Office noted in its year-end review, the government benefited from a bit of good fortune to achieve 2013's reported $680 billion deficit:

"First, Fannie Mae made a one-time payment to the Treasury of around $50 billion resulting from a revaluation of certain tax assets that significantly increased its net worth.

Second, because both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were profitable in 2013, the companies were required to make quarterly payments (totaling $47 billion) to the Treasury in amounts related to the increase in their net worth."

In evaluating the degree of operational deficit reduction that has occurred, that $97 billion in likely non-recurring good fortune should be separated out. After removing the effects of TARP accounting and the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac payments, a comparison of fiscal 2009 and 2013 results shows that the deficit as a percentage of GDP fell by less than one-half during that time:

The $1.238 trillion above is far greater than the amount the Obama administration "inherited." The previous administration had nothing to do with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, commonly known as the "stimulus plan," which Congress passed in February 2009. In October 2009, the administration estimated that about $300 billion had been "put to work" through September 30, fiscal 2009's year-end.

Even though the Recovery Act activities have virtually ended, overall spending in the government's day-to-day operations has not come down, and non-defense spending has actually grown by double-digits:

Clearly, the Obama administration's spending has gone far beyond what it "inherited." The reported deficit has come down from its 2009 level primarily because of increased tax and other collections, which have grown by 32 percent from $2.105 trillion to $2.774 trillion during the past four fiscal years.

CBO optimistically projects that the deficit will come down to 2.1 percent of GDP in 2015. But the situation deteriorates steadily after that. CBO earlier this year projected that “federal debt held by the public would reach 100 percent of GDP in 2038, 25 years from now, even without accounting for the harmful effects that growing debt would have on the economy…. Moreover, debt would be on an upward path relative to the size of the economy, a trend that could not be sustained indefinitely.”

So the near-term gains haven’t been quite as rosy as the administration would like to project, and the long-term situation remains dire. Washington’s lack of seriousness is profoundly troubling.

Top Reads at The Fiscal Times: