Can we be serious about unemployment for a minute, please? The Bureau of Labor Statistics put out its monthly jobs report this morning, and the headline number was 7.0 percent unemployment, down from 7.3 percent a month earlier. It was a great report by almost all accounts – “tidings of comfort and joy,” Reuters’ Felix Salmon called it, in the spirit of the season – and stocks jumped in response to the headline figure and the strength underlying it.

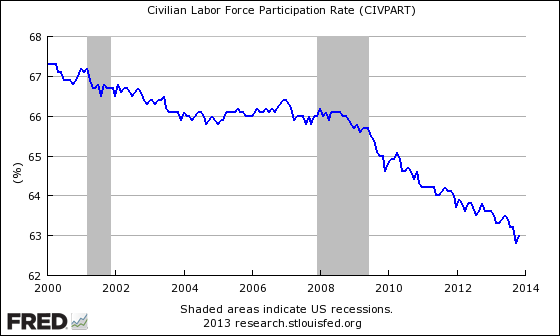

Before we get too excited about an unemployment rate as low as 7 percent for the first time in five years, though, let’s take a look at this chart of the labor force participation rate. It tracks the percentage of Americans actively involved in the labor force, and back in 2000, it hit a post-World War II high. Today, it’s near its lowest level since 1978.

Yes, the seasonally adjusted labor force participation rate ticked up from 62.8 percent in October to 63 percent in November, suggesting that the unemployment rate fell because more people found jobs and not because they got discouraged and dropped out of the workforce. And yes, the so-called underemployment rate, which includes those discouraged job seekers and part-time workers who would prefer full-time jobs, fell to 13.2 percent from 13.8 percent in October. Those are signs of progress.

Related: Fast-Food Worker Strikes: Will They Do Any Good?

But remember back in 2009, when the unemployment rate hit 10 percent? Well, a higher percentage of working-age Americans was in the labor force then than now, even though the nominal unemployment rate is three full percentage points lower. “Participation in the workforce at a four decade low,” said Mark Hamrick, Washington bureau chief of Bankrate.com. “This isn’t your father’s unemployment rate.”

Jim Chessen, chief economist for the American Bankers Association, pointed out that if the labor participation rate right now were at the average level for the past 10 years, the unemployment rate would actually be closer to 11 percent.

The number of people who now have jobs is still 1.8 million people below where it was when the recession officially started in December 2007. At the current pace of job gains, it will be nine more months before that measure returns to pre-recession levels.

The Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Washington that focuses on low and middle income workers, estimates that there are some 5.7 million Americans – the majority of them of prime working age – who are not even looking for work anymore and aren’t counted in the monthly BLS figure.

It isn’t just low-wage menial workers who are sitting on the sidelines, said Elise Gould, an economist with EPI. “When we look at the unemployment rates of various demographic groups, it’s elevated across the board.”

This represents a huge amount of wasted economic potential, as the productive capacity of millions of potential workers goes unused.

The stubborn refusal of the labor force participation rate to come out of its downward dive over the past five years may force the Federal Reserve Board to re-think what it considers an acceptable level of unemployment in the U.S.

“The continuing disappointment in labor supply will prompt some soul-searching at the Fed, where the house view has been that the participation rate would bounce back once job creation picked up,” J.P. Morgan economist Michael Feroli wrote in a research note today. “Over the past two years the labor market has created almost 4-1/2 million jobs, yet the participation rate has continued to decline. At some point the Fed will have to accept that the labor supply is trending lower, and hence that the decline in the unemployment rate truly represents progress toward their full employment mandate.”

Feroli suggested that it may push the central bank to begin easing back on its quantitative easing program – the so-called taper – sooner than it otherwise might if policymakers determine that broad demographic and economic changes have permanently altered the country’s long-term labor participation rate.

Follow Rob Garver on Twitter: @rrgarver

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: