At her confirmation hearing before the Senate Banking Committee this month, Janet Yellen faced questions from senators on both sides of the aisle about whether the central bank’s monetary stimulus is an “elitist,” “trickle down” policy that disproportionately benefits the wealthy and exacerbates income inequality.

"One of my concerns is that the Fed’s monetary policy doesn’t do enough to serve all Americans," said Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH). “It’s not clear to me, and more importantly, it’s not clear to the many Americans who have not seen a raise in a number of years, that this policy increases wages and incomes for workers on Main Street.”

Related: Are We Suffering from 'Secular Stagnation?'

It’s a charge that critics of the Fed have been leveling for a long time about the bank’s extraordinarily low interest rates and large scale “quantitative easing” asset purchases. Ethan Harris, an economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, sums up the complaints in a new note to clients:

“Critics argue that the Fed is creating higher financial sector profits and a booming stock market, but unemployment remains high and wage growth remains low. By stimulating home prices, the Fed is making it harder for low-income families to buy homes. By keeping interest rates low, the Fed is punishing people on fixed incomes. Finally, by pushing up inflation, the Fed is lowering the real spending power of average Americans. In sum, the critics conclude, the Fed should stop hurting Joe Six Pack and immediately normalize monetary policy.”

Do those charges hold up? Yellen, a key architect of the Fed’s stimulus measures, acknowledged that “low interest rates harm savers,” but they also have a broader ripple effect that extends through the economy, helping both the unemployed as well as those who have jobs and would benefit from increased wages that would result from a stronger economy. A couple of recent reports shed some more light on Yellen’s defense.

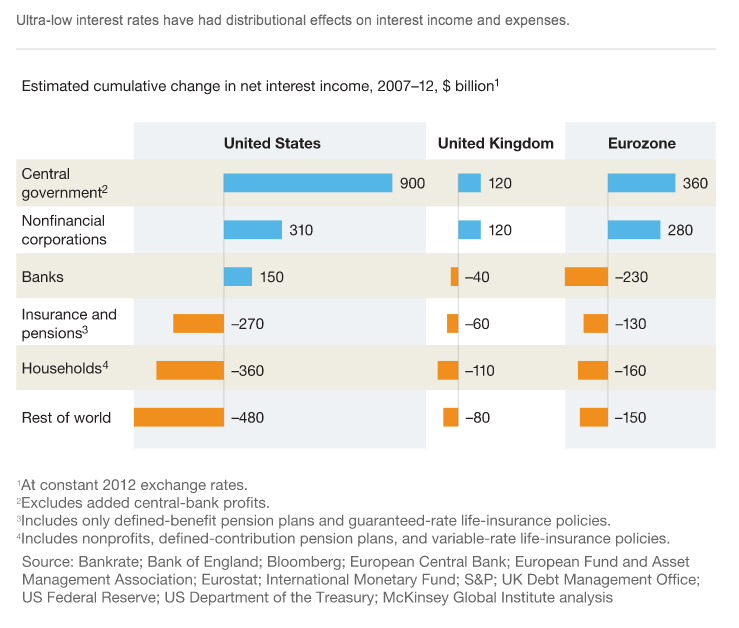

The first is a discussion paper released this month by the McKinsey Global Institute that examines how and how much low rates have hurt savers. The authors looked at how different players in the U.S., U.K. and Eurozone economies have fared under ultra-low interest rates over the last five years. They found that the governments in question benefitted by $1.6 trillion, while non-financial companies and U.S. banks – but not European ones – also came out winners. (Troublingly for the economies being studied, though, higher corporate profits have not resulted in higher corporate investment, the report finds, “possibly as a result of uncertainty about the strength of the economic recovery, as well as tighter lending standards.”)

The losers from years of ultra-low rates, according to McKinsey, have been pension plans, life insurers and, yes, households. McKinsey found that households in these countries have lost $630 billion in net interest income, including some $360 billion lost in the U.S.

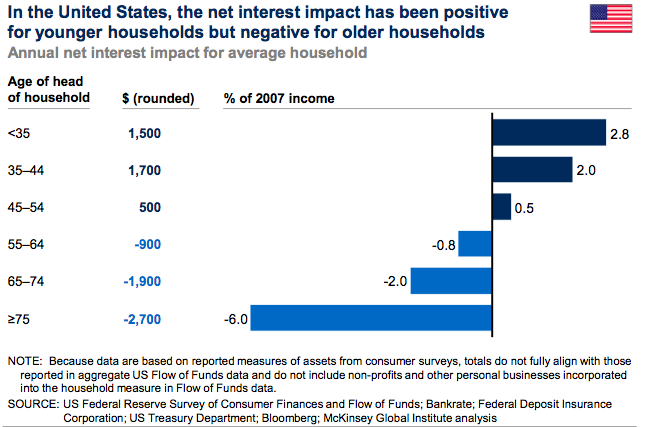

Those numbers don’t look good for Joe Six Pack, but the details of McKinsey’s findings make them appear decidedly better. The authors note that the effects of low interest rates vary greatly by age group (see the McKinsey chart below), with younger households that are net borrowers benefitting and older savers losing out. Households headed by someone between the ages of 35 and 44 have gotten, on average, $1,700 more in annual income because of the lower rates, while those headed by someone 75 or older have lost $2,700 a year.

Here are the key lines, though, for those worried about a widening income gap: “Across income percentiles in the United States, the richest 10 percent own about 90 percent of net financial assets,” the McKinsey report notes. “It is this group whose net interest income has fallen, while other income groups have seen minimal change.”

Interest income is only part of the picture, of course, and the McKinsey report notes that the hits to household income may be offset by gains in asset prices. House prices in the U.S. and U.K. may have been as much as 15 percent higher at the end of 2012 than they would have been without ultra-low rates, McKinsey’s report says. (Surprisingly, the report found that the impact of low interest rates on equity prices may be smaller than is widely thought.) “If one accepts that house prices and bond prices are higher today than they otherwise would have been as a result of ultra-low interest rates, the increase in household wealth and possible additional consumption it has enabled would far outweigh the income lost to households,” the authors write.

Those rising asset prices have been they key mechanism widening the wealth gap between “haves” and “have nots,” but they don’t necessarily mean that Joe Six Pack is suffering more than he would have been. And as Merrill Lynch’s Harris detailed in his note to clients on Friday, tightening monetary policy woudn’t be an effective solution to the problem. Harris took on criticism of the Fed’s policies point by point and offered a more detailed long-term defense than the Fed’s incoming chairwoman did at her hearing:

- Income inequality has been rising globally for much longer than the Fed has been driving interest rates down or making its “quantitative easing” asset purchases. The share of income going to the top 1 percent of households in the U.S. has been rising since the 1970s, and has continued whether the Fed was raising rates or lowering them.

- The labor market recovery since the Great Recession is only now getting to the point where wages may rise. That’s because, after an economic downturn, business profits tend to bounce back first as the high rate of joblessness gives workers little negotiating leverage and keeps wages down. It’s only after the recovery is further along and the unemployment rate drops that employers face a more pressure to raise wages. “Ironically, critics of the Fed are suggesting that the Fed should give up on moving the economy into the second, labor-friendly, stage of the economic expansion,” Harris writes.

- Fueling the housing recovery doesn’t just help the wealthy. “Lower interest rates help raise home prices — and stop foreclosures — precisely because they make homes more affordable for everyone,” Harris writes, adding that the National Association of Realtors Housing Affordability Index hit a record high earlier this year, even as home prices continued their rebound. “Again,” Harris says, “the irony here is that by doing exactly what critics favor—and threatening to taper—the Fed is hurting affordability for low-income people.”

- The argument that rising inflation undercuts consumers’ spending power stems from what Harris calls “a fundamental misunderstanding of the word ‘inflation.’” The term refers to “a generalized rise in the price of everything—goods, services and labor,” with the Fed’s ultimate goal being to push inflation back to 2 percent and to have working wages grow at a more normal pace of 3.5 percent to 4 percent.

- Harris sums up by noting that raising rates to help savers today could backfire by sapping economic momentum – and that Japan’s long struggles with a stagnant economy serve as a cautionary tale in this regard. “Raising interest rates in the U.S. today is a great way to penalize savers in the years ahead,” Harris argues.

So, yes, the Fed may be making the rich even richer right now, but the ultimate goal is to restore interest rates to more normal levels by restoring the economy to faster growth. “As in every business cycle recovery, easy Fed policy has temporarily exacerbated the long-term widening of income disparities, but ultimately easy policy means low unemployment and stronger labor income,” Harris writes. “Fortunately, the Fed understands that the fastest path between two points is not always a straight line.”

Unfortunately for many Americans, the fastest path can still feel awfully rocky.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: