The $350 billion in state and local aid included in Democrats’ $1.9 trillion Covid relief package is proving to be another point of contention, even among Democrats. Several Democratic senators have reportedly pushed for changes to that portion of the legislation, fueled in part by concerns that states could respond to an infusion of more federal aid by cutting taxes instead of devoting the additional funding to pandemic-related needs.

“We could distribute billions to the states, and they turn around and lower taxes — there are governors talking about that, and it’s not the point here … there should be a prohibition against voluntarily diminishing revenues,” Sen. Angus King (I-Maine), who caucuses with the Democrats, told The Washington Post last week.

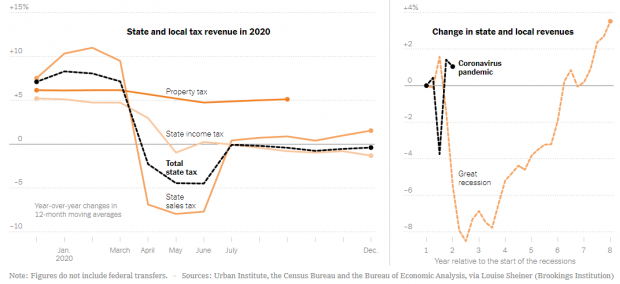

State shortfall not as bad as feared: Nearly a year after the first coronavirus-related lockdowns, data show that the impact on most state budgets has been far less devastating than early forecasts had warned.

“Early in the pandemic, state and local governments appeared to be in danger of losing hundreds of billions of dollars — or by some estimates upwards of $1 trillion — in revenue,” the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget noted recently. “This worst-case scenario has thankfully been avoided, due in large part to the robust federal response and a relatively strong but uneven partial economic recovery. While some state and local governments are still hurting, others are doing quite well and hardly any are doing as badly as feared.”

As Mary Williams Walsh of The New York Times reports, The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center has found that total state revenues from April through December were down just 1.8% compared to the same period in 2019.

An analysis by Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zandi pegged the state and local shortfall at about $60 billion through fiscal year 2022 (including the federal aid already approved). By contrast, a January analysis by the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities said that states, localities, tribal nations and U.S. territories face total shortfalls of about $300 billion through fiscal year 2022 (again, after factoring in previously approved aid).

“Most states (34) still project lower revenues for the current fiscal year than they expected before the pandemic struck, our analysis of these data indicates,” the center’s Michael Leachman and Elizabeth McNichol wrote in a report published last week. “In some cases, the forecasts are much lower.”

Better targeting? Sen. King and others have proposed directing some of the proposed $350 billion in aid for state and local governments toward investments to improve broadband, and some economists have suggested that repurposing some of the money for infrastructure could be more useful. “Say they would go to $150 billion for state and local aid — that would give them $150 billion for infrastructure,” Zandi told the Post.

Jason Furman, a former top economist in the Obama administration, similarly told the Post that the proposed $350 billion in aid exceeds the immediate need: “It should either be better defined by focusing on what it should be spent on, like infrastructure or broadband; what it should not be spent on (like tax cuts); or the total should be reduced.”

Some Democrats and economists argue that states’ pandemic-related costs are set to jump as they push to reopen schools and provide vaccinations — and that many local governments are hurting worse than states and still need significant help. Those backing a larger aid infusion also warn that the pandemic isn’t over yet, and emerging variants create new uncertainty and risk for budgets. And they note that the unequal economic toll of the pandemic, which has hurt lower-income workers far more than those higher up on the ladder, has both blunted state revenue losses and increased the need to spend, so that focusing only on better-than-expected revenues provides an incomplete picture.

On top of all that, they argue, the goal shouldn’t just be to restore the pre-pandemic status quo but to “build back better,” as President Biden put it — meaning that state and local investment plans should be updated. “They’ll need to hire back teachers, health care workers, and others to support a robust recovery,” CBPP said in its report. “Restoring that level of job loss will require some $40-50 billion alone.”

Read more at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the Economic Policy Institute, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities or The New York Times.