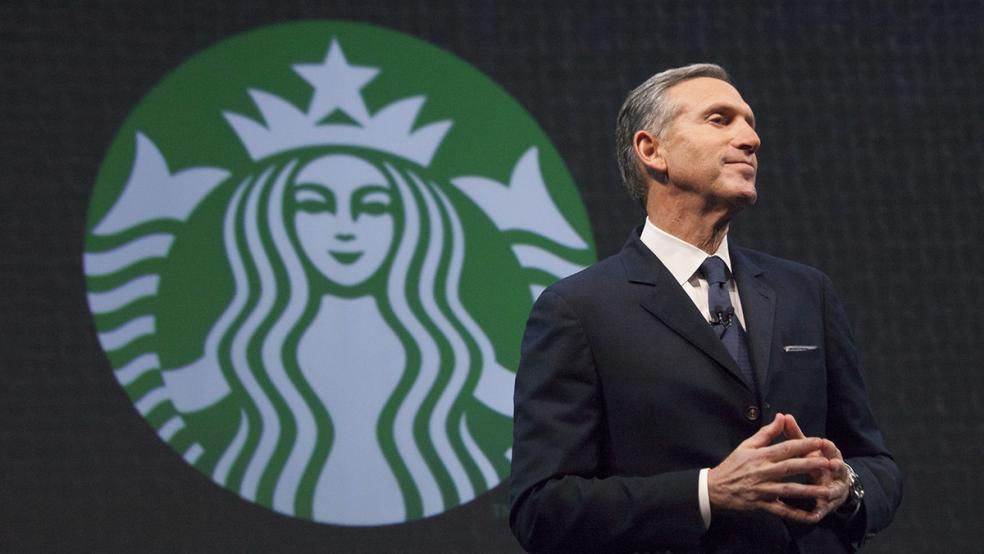

Starbucks founder Howard Schultz told “60 Minutes” Sunday that he is considering a run for president in 2020, possibly as a “centrist independent,” and one of his top issues is the growing national debt. "I look at both parties. We see extremes on both sides. Well, we are sitting today with approximately $21.5 trillion of debt, which is a reckless example, not only of Republicans, but of Democrats, as well, as a reckless failure of their constitutional responsibility," Schlutz said.

In an interview with CNBC Monday, Schultz returned to the theme, saying, "I think the greatest threat domestically to the country is this $21 trillion debt hanging over the cloud of America and future generations.” Asked about the possibility of raising taxes to address the debt, Schultz said that, “the only way we’re going to get out of that is we’ve got to grow the economy, in my view, 4 percent or greater, and then we have to go after entitlements.”

Schultz, a billionaire who describes himself as a lifelong Democrat, was critical of the Republican tax cuts that went into effect last year, calling them “fool’s gold” that won’t help the people who need it most. But Schultz has distanced himself from the Democratic Party as he moves toward what he sees as the center, telling CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin that, “so many voices within the Democratic Party are going so far to the left, and I ask myself, how are we going to pay for all these things, in terms of things like single-payer, or people espousing the fact that the government is going to give everyone a job. I don’t think that’s realistic, and I think we’ve got to get away from all of these falsehoods and start talking about the truth and not false promises.”

Schultz quickly drew criticism from Democrats, some of whom warned that he risked handing President Trump an easy reelection if he runs as an independent and splits the party. (Trump appears to be no fan, either, tweeting that Schultz "doesn't have the 'guts' to run for President!")

But Schultz could also meet resistance for his position on the national debt, which has become less of a focus even for establishment Democrats. Writing in Foreign Affairs, Democratic insiders Jason Furman, who served as President Obama’s chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, and Lawrence H. Summers, who served as Treasury Secretary in the Clinton administration and director of the National Economic Council under Obama, argue that politicians in Washington should stop worrying so much about the national debt.

While noting that the U.S debt will be about the same size as the economy within the next decade – a debt level “unprecedented for the United States during a time of economic prosperity” – Furman and Summers say that “deficit fundamentalists” need to start listening to the “deficit dismissers” who believe there are more important problems that need to be addressed first.

The authors summarize the deficit dismisser argument as follows:

“Long-term structural declines in interest rates mean that policymakers should reconsider the traditional fiscal approach that has often wrong-headedly limited worthwhile investments in such areas as education, health care, and infrastructure. Yet many remain fixated on cutting spending, especially on entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicaid. That is a mistake. Politicians and policymakers should focus on urgent social problems, not deficits.”

Furman and Summers say they recognize that fiscal constraints are real and can’t be ignored forever. But they counsel a middle way of sorts, in which policymakers avoid adding to deficits when the economy is strong, and add to the debt only during downturns, when the economy needs fiscal stimulus. In good times, new social spending should be paid for, but no effort should be made to reduce the overall debt. “This middle course would tolerate large and growing deficits without making a major effort to reduce them—at least for the foreseeable future,” the authors write. If the debt does become a real financial problem, alarm bells will ring in the markets in the form of higher interest rates, giving policymakers a clear signal to change course.

At the same time, Furman and Summers say that policymakers across the political spectrum need to recognize that the federal government needs higher revenues to maintain public investments and pay for rising entitlement spending. The “the United States has more of a revenue problem than an entitlement problem,” they write. “U.S. spending on social programs ranks among the lowest in 35 advanced economies, yet the country has the highest deficit relative to its GDP in the group. That is because the United States brings in the fifth-lowest total revenue as a share of GDP among those 35 countries.”

The bottom line: The “economics of deficits have changed,” the authors say, which means that policymakers should move “away from many of the old deficit and entitlement-focused orthodoxies—but not to wholesale abandonment of fiscal constraints.”