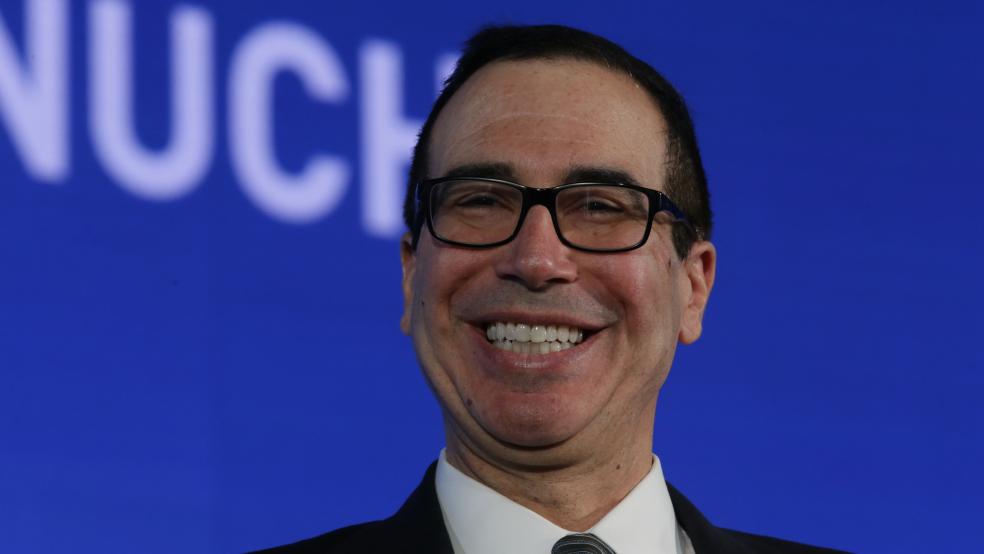

For months, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has claimed that the Republican tax plan will more than pay for itself by generating faster economic growth, adding that more than 100 people in his department were “working around the clock” on modeling various estimates of the plan’s effects. But the promised Treasury analysis supporting that claim had been conspicuously missing from the debate over the tax plan.

Maybe the administration was better off that way.

The Treasury Department on Monday released a one-page “analysis” of the Senate tax bill — 470 words, including footnotes, on a roughly 470-page bill — asserting that the Trump administration’s overall economic agenda would generate about $1.8 trillion in additional revenue over 10 years, more than offsetting the roughly $1.5 trillion cost of the tax cuts.

But the assumptions in the Office of Tax Policy (OTP) report make it read less like a rigorous analysis of the tax plan’s real-world effects and more like an exercise in wish fulfillment. “It would appear that OTP was pressed to validate somehow the secretary’s position that the tax bill would pay for itself,” Bill Hoagland, a former Senate Budget Republican staff director and senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told Bloomberg.

And the backlash was swift and brutal.

Problem No. 1: Simply Assuming Faster Growth. To get to its $1.8 trillion revenue figure, the analysis assumes that long-term economic growth would reach an annual rate of 2.9 percent over the next 10 years, a level far higher than the 2.2 percent growth it previously expected over that timeframe — and far rosier than most other economic forecasts. (“There is an old joke about economists debating how to get off a desert island. Step one, they agree, is ‘assume a boat’. The Treasury Dept just assumed a boat,” The New York Times’s Jim Tankersley tweeted.) By contrast, the Joint Committee on Taxation projected that the Senate tax plan would increase GDP by a total of 0.8 percent over the next decade. “We acknowledge that some economists predict different growth rates,” Treasury’s report said.

Where did the new Treasury growth rate come from? The Trump administration’s 2018 budget — a budget that assumed that tax reform would not increase the deficit and that also included some different tax code changes than the ones being finalized by Congress, such as a corporate tax rate of 15 percent rather than 20 or 22 percent. Plus, as Vox’s Matthew Yglesias points out, the administration’s budget was summarily rejected by Congress.

Problem No. 2: Assuming Other Policy Changes That Haven’t Happened Yet. The new report offers little in the way of detailed explanation for how the economy would accelerate to that faster growth rate. It says about half of the additional output would result from corporate tax changes, while the rest would come from tax changes for pass-throughs and individuals as well as “a combination of regulatory reform, infrastructure development, and welfare reform.” Reporters and critics were quick to point out that many of those other reforms have yet to be detailed or written, let alone passed.

Problem No. 3: The Numbers Don’t Reflect What Republicans Say Will Happen. The $300 billion left over under the Treasury’s analysis is likely to disappear quickly if tax cuts set to expire after 2025 in the Senate bill are extended. “Keeping those tax cuts in place—as Republicans say a future Congress will—would likely consume much if not all of any incremental revenue,” The Wall Street Journal’s Kate Davidson and Richard Rubin report.

Problem No. 4: The Tax Cuts Don’t Pay for Themselves. While the report may nominally give the Trump administration and congressional Republicans more ammunition for their tax-cutting sales pitch, it ultimately reinforces what outside analysts have said — the tax plan alone won’t pay for itself, and the assumptions needed to show otherwise are fairly dramatic.