President Trump’s first appearance at a meeting of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization this week was an opportunity to set the record straight.

Trump could have used his speech to the group’s assembled leaders on Thursday to indicate that since the presidential campaign last fall, when he demonstrated a profound misunderstanding of how the alliance is funded, he has taken the opportunity to educate himself about the relationship between the U.S. and its European allies.

Related: Trump’s All Guns, No Butter Budget Is a Bust with Lawmakers

He might also have reassured allies that the United States remains committed to Article 5 of the organization’s founding treaty, which promises that if one member is attacked the others will all come to its aid. During the campaign, he worried NATO allies with talk about not honoring the mutual defense treaty, or withdrawing from NATO altogether.

However, Trump did neither. Instead, he confirmed the worst fears of many of the country’s closest allies by indicating that he still sees the relationship between the U.S. and its NATO allies as completely transactional, and that he still doesn’t seem to understand how the organization is funded.

Not only did Trump make no mention at all of the United States’ Article 5 obligations -- something every president since Truman has done explicitly -- he berated other leaders for not paying their “fair share” of the alliance’s costs.

“Twenty-three of the 28 member nations are still not paying what they should be paying for their defense," Trump said. “This is not fair to the people and taxpayers of the United States, and many of these nations owe massive amounts of money from past years.”

Related: NATO - Everything You Need to Know About the Alliance Donald Trump Says Is ‘Obsolete’

To be clear, Trump is not the first American president to want NATO members to increase their defense spending. In 2014, at a summit in Wales, then-president Barack Obama concluded an agreement among the members that those who were not already meeting the suggested 2-to-3 percent of GDP spending target would work to get there over the next decade.

Trump, though, seems to think that NATO is something like a club, in which dues must be paid in order to enjoy the benefits of membership. But it doesn’t really work that way. NATO, as an organization, has relatively few tangible military assets that are jointly funded.

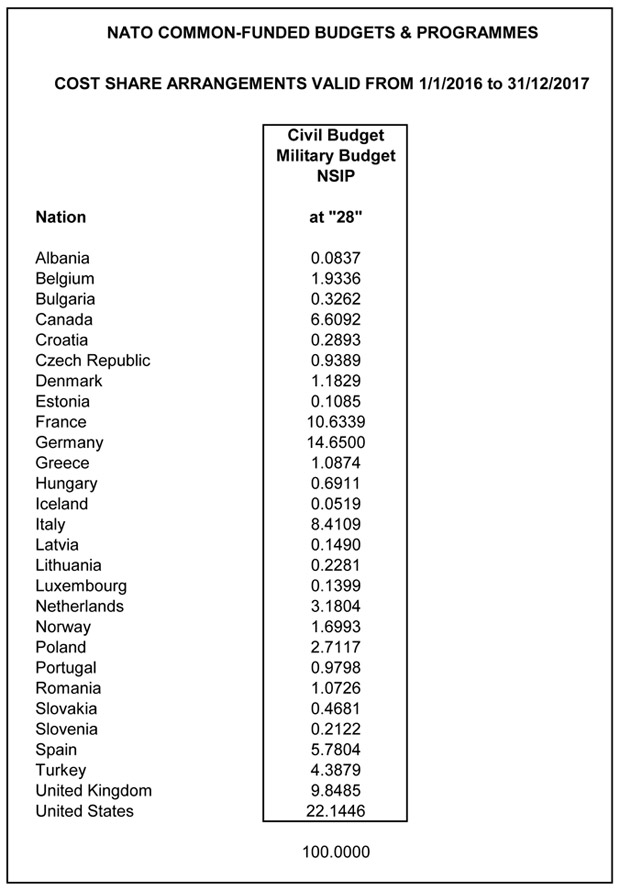

The organization maintains a headquarters facility, a joint command-and-control structure and a relatively small program organized around training and response-readiness programs. Those projects are funded by assessments on all members, which are based on a formula that takes into account the various nation’s GDP.

The U.S. pays the largest share -- about 22 percent -- while Germany pays 14.7 percent, France 10.6 percent, the UK 9.9 percent, and smaller nations commensurately smaller amounts.

Related: 5 Ways Trump’s Big Talk About Supporting Our Troops Falls Short

But the sum total spent on this direct funding of NATO is about $1.7 billion per year. That makes the U.S. share about $376 million -- a rounding error in the federal budget.

Importantly, there is no standing NATO army, navy, or air force that the U.S. is picking up the tab for as other countries look away.

The vast majority of NATO “funding” comes indirectly, in the form of countries’ expenditures on their own armed forces and other forms of national defense.

To be sure, the U.S. spends far more than any other NATO member -- or any other country in the world, for that matter -- on national defense. Taken as a share of total military spending by all NATO countries, the U.S. spends vastly more than the rest of the organization combined, accounting for nearly three-quarters of total outlays. It also spends more as a percentage of GDP -- 3.61 percent -- than any other NATO country.

But it makes little sense to try to hold tiny landlocked nations in the middle of Europe to the same standard as a country like the United States, which has obvious interest in projecting military power far beyond its borders and into parts of the globe where NATO member have few if any real interests.

Related: How Trump's Saudi Arms Deal Could Backfire on the US

The Czech Republic could theoretically fund a navy, but they’ve got nowhere to put it. Similarly, Iceland has little use for a large standing army.

Trump might have taken the time to understand these things before arriving in Brussels this week, and could have pleasantly surprised U.S. allies with a more nuanced understanding of the alliance that has helped keep the peace in Europe for generations.

Rather than rise to the occasion, though, he merely confirmed the worst suspicions of America’s oldest allies.