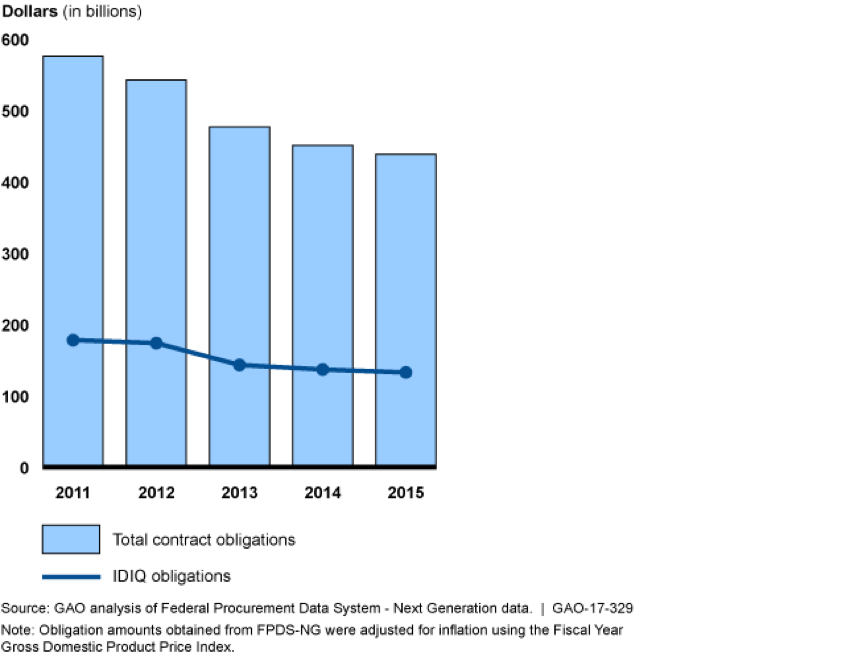

Over the past five years, the federal government has committed to spending as much as $130 billion a year on supplies and services through unusual contracts that break the mold of traditional contracting practices.

Typically, when federal agencies buy anything from jetfighters to computer services to paper clips, they throw open bidding on major contracts to a number of eager businesses that compete to offer the best price, the most experience and the promise of meeting a deadline. Larger projects — like building a battle ships — are broken into scores of subcontracts that are bid out in similar fashion.

Related: Pentagon’s Sloppy Bookkeeping Means $6.5 Trillion Can’t Pass an Audit

Yet another type of contract, known as “indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity,” has become common at the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, Health and Human Services and Veterans Affairs over the last decade or so, according to a new report by the General Accounting Office (GAO), with the Pentagon accounting for about 68 percent of all such contracts between 2011 and 2015.

For these so-called IDIQs, the government hand picks one or more contractors to commit to delivering products and services in the future and sets a ceiling on how much money will be spent overall. Awards are for a specified number of years with renewal options, but usually for no longer than five years.

Since 2005, thousands of these multiple-award, indefinite quantity programs have been launched, many with multi-billion-dollar spending ceilings. About two-thirds of government-wide IDIQ obligations were for services, such as architecture and engineering and IT support, while the remainder were for products.

Related: Why the Pentagon Budget Is Out of Control

The contracts are premised on maximizing the government’s flexibility in determining the exact quantity of products and services it requires and when they should be delivered. On the face of it, this practice offers the government some definite advantages, including maximum flexibility in purchasing services and products and controlling costs. Some officials said it was much easier and faster to place an order under an existing IDIQ contract than to award a separate contract when a specific need arose.

“IDIQs, when properly used, benefit the government,” said Brian Friel, founder of Nation Analytics and an expert on federal contracting. “Things can get awarded more quickly, so you can reduce the cost of acquisitions.... It’s flexible, generally fast, and it allows the government to not lock itself into a quantity it doesn’t need.”

On the other hand, impromptu decision-making on government acquisitions can sometime lead to errors or bad deals. Friel said the program has been subject to misuse and even scandal in the past, particularly when just one company is granted a contract with an open-ended scope. In cases like that, it may not always be the case that the government is getting the lowest cost or the best service.

Related: How the Pentagon Cooks the Books to Hide Massive Waste

“Over the years, there have been a lot of concerns with improper use,” Friel added in an interview. “The government pre-selects companies, so some other companies are locked out for an extended period of time.”

The contracts, while lucrative, can also pose risks to the contractors that secure them. Government officials can arbitrarily decide how much to buy and when to demand delivery. And agencies are under no obligation to spend all the money set aside for a project — leaving contractors at the mercy of government decision-making.

Related: Budget Watchdog Tells Trump Government Spending Is on an Unsustainable Path

The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) states a preference for multiple-award IDIQs, according to the GAO report, presumably to encourage more competition and to avoid cozy relationships between government managers and sole-source contractors. Yet roughly 60 percent of the dollars spent government-wide on these sorts of contracts were obligated through single-award IDIQs.

“For the competed single-award contracts, contracting officials cited various reasons for choosing a single-award IDIQ approach, such as the need to build and maintain knowledge as orders were awarded over time,” according to the GAO report. “For about one-third of the multiple-award IDIQ orders GAO reviewed, DOD did not provide an opportunity for all contract holders to compete due to urgency or other reasons.”

In many cases, companies holding those sole contracts had problems completing their tasks or delivering services on time. For instance, 10 of the 18 single-award IDIQ contracts GAO reviewed at the Defense Department were not completed — generally because only one contractor could meet the need, according to the report.

Related: Deficit Hawks Take Trump on an Ominous Tour of the Fiscal Cliff

Moreover, some companies that have participated in multiple-award IDIQs have lost money when the government decided to stay well below their spending ceiling. “There’s no way to have a return on investment when no actual paying work flows through a contract vehicle,” according to Friel.

The GAO study was requested by Sen. Clair McCaskill of Missouri, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee.