It didn’t take long for President-elect Donald Trump and his senior advisers to begin backing away from Trump’s promise to provide “insurance for everybody” as part of his incoming administration’s evolving plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

Without ever explaining precisely what he had in mind, Trump told The Washington Post last weekend that he would push for something resembling universal coverage that would insure even more than the 20 million Americans who currently benefit from Obamacare.

Related: Tom Price Makes a Big Claim: People Won’t Get Shafted on Health Care

Trump’s boasting that he was on the verge of unveiling a comprehensive health care plan to replace Obamacare that would offer cheaper premiums, better choices for consumers and near universal coverage caught congressional Republicans by surprise. The billionaire businessman’s boast has highly complicated their effort to devise a realistic plan that can win the support of rank and file lawmakers, the health care and insurance industries and a nervous public.

Even Rep. Tom Price (R-GA), Trump’s choice to head the Department of Health and Human Services was vague during his Senate confirmation hearing Wednesday on how many more people would receive coverage once the Republicans fully overhaul the health care system. Price promised Americans “access” to the highest quality care and coverage possible but offered no guarantees that everyone could afford it.

During an interview on Tuesday with Axios.com, Trump appeared to backtrack somewhat on his promise of insurance for everybody, saying that he wanted to find a “mechanism” – perhaps Medicaid block grants -- to help the poorest Americans. "You know there are many people talking about many forms of health care where people with no money aren't covered.” Trump said. “We can't have that.”

The following day, Vice President-elect Mike Pence told CNN that he interpreted Trump’s comments to The Post to mean “making insurance affordable for everyone.”

Related: The Three-Way Battle for Obamacare Repeal

“I think it means making insurance affordable for everyone, but also allowing for the kinds of reforms in Medicaid on a state by state basis that will ensure – that will make sure that we have healthcare coverage for the most vulnerable in our society,” Pence told CNN’s Dana Bash.

On the surface, at least, Trump and his top advisers appear to be struggling to forge a consensus on a plan they can sell to Congress and are sending up a series of trial balloons. But a less charitable interpretation is that Trump is engaging in a classic bait-and-switch gambit, with some low-income single Americans having the most to lose from it.

After briefly dangling a promise to deliver universal coverage to Americans, Trump has abruptly pulled it back and offered as a substitute an old GOP chestnut – a major overhaul of the nation’s Medicaid system, which was expanded to 133 percent of the poverty line under President Obama and included able-bodied people without dependent children.

Contrary to the Republicans’ promises of improvements and broader coverage, some analysts have warned that block granting Medicaid could have an adverse impact on some of the country’s poorest people.

GOP efforts to transform Medicaid from a federal entitlement program covering all eligible low-income Americans into block grants to the states actually dates back to the Reagan administration of the 1980s. While the 50-year-old Medicaid program today is a health care lifeline for millions of children, pregnant women, the disabled and the poor, GOP leaders have long complained about runaway spending, fraud and waste.

Interestingly, since Medicaid was conceived as a state-based program, states are not required to participate in the program. But there has been full participation in the core program since 1982. Like all health care programs, Medicaid is expensive, and a number of Republican governors and their legislatures have opted out of the expansion.

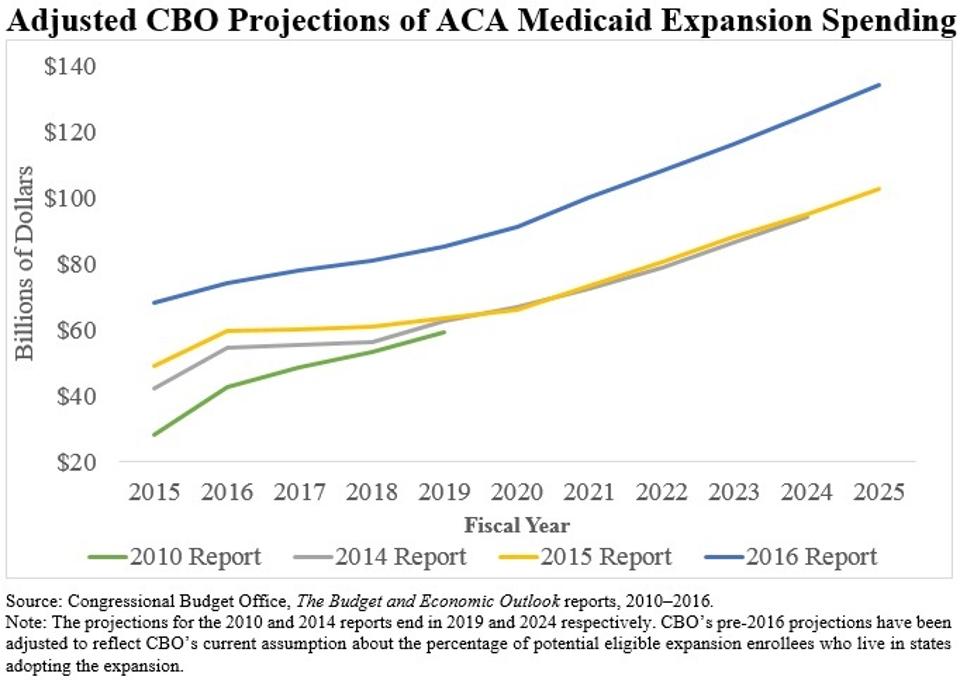

At a time when the federal debt is about hit $20 trillion, the Congressional Budget Office is warning the new administration and all the federal agencies that belt-tightening is prudent.

Related: Trump Says His Plan Would Provide ‘Insurance for Everybody’

The joint federal-state Medicaid program currently covers nearly 72 million Americans and spent approximately $545 billion during fiscal 2016. That’s the equivalent of more than 15 percent of all health care spending in the U.S., according to congressional figures.

Leading GOP figures including House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin and Price have long championed the idea of block grants to contain or cap future spending and to give states more authority in regulating the program and setting eligibility standards.

“For too long, states have been treated like junior partners in the oversight and management of the Medicaid program – forced to go through long and cumbersome waiver processes just to make most changes to their program,” Ryan wrote in his “GOP Better Way” health care reform proposal released last summer.

Ryan and other Republican leaders contend that governors and state legislatures are closer to patients in their states and are better equipped to seize on opportunities to achieve savings and crack down on fraud and abuse. However, critics warn that it would likely give states sweeping new authority to tighten eligibility, cut benefits, and generally make it much harder for people to enroll.

Related: 8 Big Changes Under Tom Price’s Obamacare Replacement Plan

“Block grants are about producing federal savings by shifting costs and risks to states,” said Edwin Park, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank. “To compensate for the federal funding cuts, states either have to cover much more of their own costs by raising taxes, cutting other spending, or far more likely, taking any flexibility they’re given to institute cuts to their Medicaid programs – whether its eligibility, benefits, provider payments and the like.”

“That likely means that many low-income beneficiaries who rely on the program will end up uninsured or under-insured,” he added in an interview Thursday. “It’s not about expanding coverage, it’s really about eventually having to make deep cuts.”

A block grant would essentially cap federal Medicaid funding as a way of achieving major savings in the coming decade. Currently, the federal government picks up a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid cost – on average 57 percent—and the states cover the rest. Under a block grant approach, however, states would receive a fixed amount based on a formula, with the states responsible for picking up any additional costs above the cap.

The states’ new block grant funding levels in most cases would be based on current or historical spending patterns, which on the surface seems fair. However, the program would be designed in a way to slow the rate of growth of funding in the coming years, gradually tightening the noose and forcing the states to adopt tighter eligibility rules, possibly including a work requirement.

Related: What Obamacare Repeal Could Mean for Your Workplace Health Plan

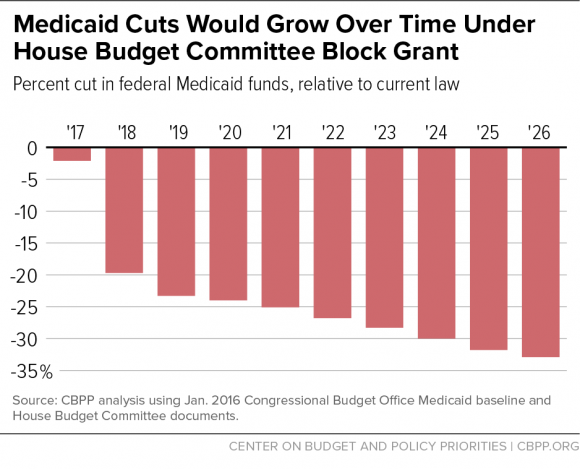

According to Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis last November, a block grant proposal contained in a House GOP budget plan for fiscal 2017 would cut federal Medicaid funding by $1 trillion — or nearly 25 percent — over ten years, relative to current law. By then, federal funding for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) would be roughly $169 billion, or about a third less than what it would be under existing law.

Another analysis by the Urban Institute of a previous block grant proposal advanced by Ryan in 2012 projected that between 14 million and 21 million people would eventually lose their Medicaid coverage.