To the surprise of many analysts, the stock market’s reaction to the election of Donald Trump has been overwhelmingly positive, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 surging to all-time highs. However, according to a new analysis from Capital Economics, one of President-elect Trump’s key promises to the business world involving the return of offshore cash to the U.S. isn’t likely to do much for the market or the economy if it is implemented.

Trump has vowed to seek changes to the tax code that would lower the tax rate on business income held overseas to 10 percent. The idea is to entice U.S. companies -- which currently have nearly $3 trillion in cash sitting offshore -- to bring the money back into the country, where it could be invested in job-creating business expansion.

Related: Trump’s Vow to Abandon the TPP Hands China a Huge Victory

However, there are a couple of problems with the assumption that money that firms return to the U.S. would immediately be ploughed into new factories or other major projects.

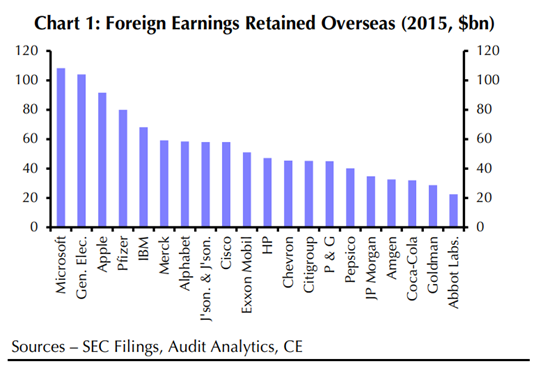

The majority of the money held overseas is in accounts belonging to a relative small number of U.S.-based businesses, and if they brought it back onshore, they probably wouldn’t invest it.

“Retained foreign earnings are concentrated among a limited number of large firms that dominate the S&P 500, many of which also have huge reserves of cash at home and are able to borrow at very low rates of interest,” writes John Higgins, chief market economist at Capital Economics. “If they wanted to invest heavily in the US economy, they could do so already without needing to bring money back from abroad.”

What they would likely do instead, Higgins argues, is return money to their investors.

“Repatriated funds are ... more likely to be returned to shareholders – as appeared to be the case during the 2004 repatriation tax holiday – via, for example, share buy-backs,” Higgins writes. “Indeed, the multinationals with the largest amounts of retained earnings overseas are typically those that have been most actively buying back their shares over the last decade.”

Related: Trump: Nobody but the Media Cares About Conflicts of Interest

Of course, Trump’s economic proposals cover much more ground than just repatriation taxes.

There’s widespread agreement among economists that if Trump’s economic proposals are implemented as he’s presented them, the result will be a temporary boost in economic growth. That would be followed, in all likelihood, by a much longer period of reduced growth as deficits pile up, government borrowing crowds out other investment, and debt service rises as a share of the federal budget.

Higgins’ colleague, Paul Ashworth, announced Tuesday that he was formally raising the growth target for the U.S. economy to 2.7 percent next year, up from 2.0 percent.

“Our new forecasts are based on the assumption that Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress agree on a fiscal package worth around $4 trillion over the next decade, equivalent to 2.4% of GDP per year,” Ashworth wrote. “Most of that stimulus will come in the form of tax cuts for high income earners and lower corporate tax rates. We suspect that any infrastructure spending boost will turn out to be much smaller than the $500 billion to $1 trillion estimates currently being thrown around. Furthermore, the impact of that spending probably wouldn’t feed through until 2018 and beyond.”

Related: Dow 19,000: Will the Fed’s Coming Rate Hikes Kill This Bull Market?

However, as with most predictions that involve actions Trump is expected to take, there are no guarantees whatsoever.

“We cannot stress enough ... that the uncertainty surrounding these forecasts remains unusually elevated,” he wrote.