Amid mounting efforts by congressional Republicans and many states to reduce the growth in the federal food stamp program, spending on the program dropped by three percent during the first half of fiscal 2016 compared to a year ago, according to new Treasury Department data.

While a three-percent drop in a multi-billion-dollar federal program may not sound like a lot, the net result is that 3.1 million fewer Americans received food subsidies under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in January 2016 than in January 2013, according to Department of Agriculture data.

Related: $74 Billion Food Stamp Program in Budget Crosshairs

During the Great Recession, SNAP was expanded to include able-bodied people adults who had no children, temporarily overturning a provision in the 1990’s that required single people to find a job within three months of receiving the benefit and work an average of 20 hours a week in order to continue to qualify.

As the program grew to 1 in 7 Americans on food stamps—including college students—or more than 46 million Americans, the program had become fiscally unsustainable. As the economy and jobs bounced back, SNAP costs began to fall as more people landed jobs.

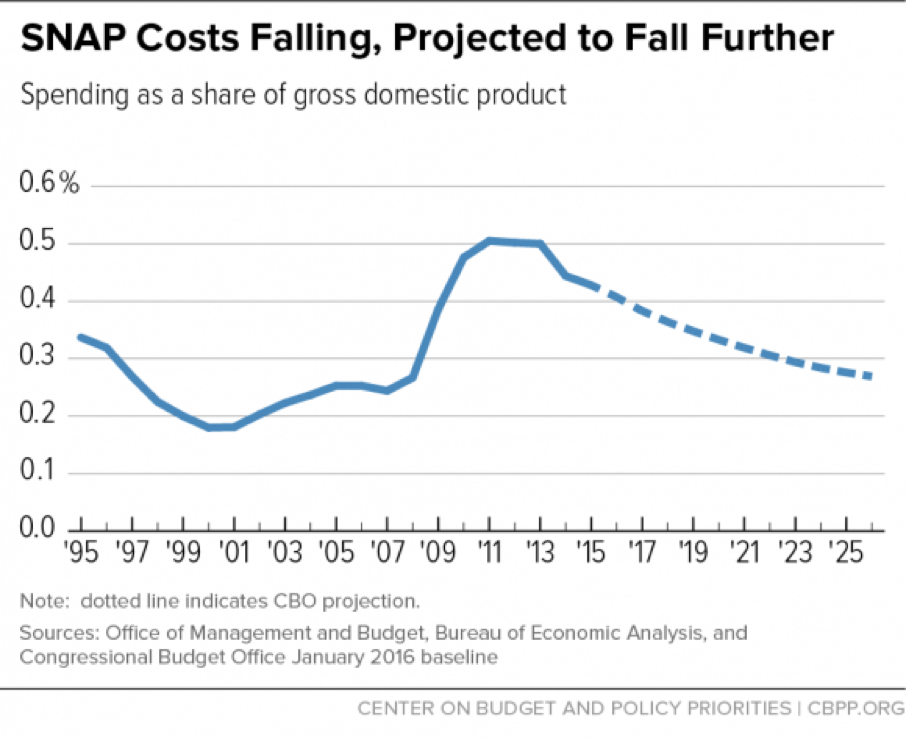

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which has long championed food stamps as an essential element of the social safety net in recessionary times, said that SNAP spending between October 2015 and March 2016 was at the lowest point for the first half of a fiscal year since 2009 when adjusted for inflation.

Dottie Rosenbaum, a food stamp expert for the center wrote on Wednesday that food stamp caseloads were falling and there was no justification for House Republicans to seek massive new cuts in SNAP for the coming fiscal year.

Late last month, the House Budget Committee adopted a budget plan that would slash food stamp spending by more than $150 billion – or more than 20 percent – over the coming decade and change the program into block grants. Rosenbaum said that a cut of that magnitude would force millions of low-income families out of the program and reduce the monthly benefits for those who remain on the rolls. The committee has sought similar cuts in each of the last five years.

Related: Food Stamp Use Plummets Amid Job Growth

“It would convert SNAP into a block grant beginning in 2021 and cut funding steeply — by $125 billion (or almost 30 percent) over 2021 to 2026,” according to Rosenbaum. “States would be left to decide whose benefits to reduce or terminate. They would have no good choices, since SNAP benefits average only $1.41 per person per meal and go primarily to poor children, working parents, seniors, people with disabilities, and others struggling to make ends meet.”

The liberal leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has argued that efforts to cut the program make little sense because SNAP has performed as it was designed to do – which is mainly to respond to the ebbs and flows of economic conditions, expanding when it is needed most and shrinking when times have improved. As a result, the organization says, SNAP isn’t contributing to long-term pressures on the budget and the deficit

The food stamp caseload dropped 11 percent in 2014 as the economy continued to improve. But some GOP lawmakers said they saw the potential for further cuts to the $74 billion program, which they complain had increased more than 45 percent since President Obama first took office. What’s more, the food stamp program for years has been troubled by rampant fraud – both by beneficiaries and merchants.

Related: The Surprising Fact of Hunger in America

As many as one million of the low-income people who will be cut from the food stamps rolls this year will be impacted by the work mandate that took effect in 21 states on April 1 in response to the improvements in the economy.

Many governors and state officials say the mandate is an important incentive for unemployed people to find work and relieve the government of significant costs. However, critics say the mandate is out of date and doesn’t address the problems structural unemployment among the poor or ill trained.

"We've seen a long-term trend toward more precarious job conditions for low-skilled workers," Shawn Fremstad, a lawyer at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, told The Washington Post. "Even if you get a job, you're not guaranteed more than 20 hours a week."