A prospective general election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton could significantly alter which states are in play this fall and heighten more than in any recent election the racial, class and gender divisions within the national electorate.

After successive campaigns in which President Obama expanded the Democrats’ electoral map options by focusing on fast-growing and increasingly diverse states, a 2016 race between Clinton and Trump could devolve principally into a pitched battle for the Rust Belt.

With a focus on trade issues and by tapping anti-establishment anger, Trump would seek to energize white working-class Americans, who Republicans believe have been on the sidelines in recent elections in substantial numbers. Trump would also attempt to peel away voters who have backed Democrats, a potentially harder task.

At the same time, Clinton could find Trump a powerful energizing force on her behalf among African Americans and Latinos, which could help to offset the absence of Obama on the ticket after two elections that drew huge minority turnout. That could put off-limits to Trump some states with large Hispanic populations where Republicans have competed intensely in recent elections.

Although polls give Clinton a solid advantage over Trump in a general election, many Democrats remain wary because of what one party strategist called “the unpredictability of Trump.” As one former member of Obama’s campaign team put it, “I feel like in some ways my brain has to think differently than it ever has.”

In Cleveland Saturday, March 12, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton criticized GOP front-runner Donald Trump for "ugly, divisive rhetoric" that she said encourages aggression and violence which is not only wrong, but dangerous. (Reuters)

Democrats will assess the landscape in several ways: which states are likely to be in play, which of those are different from past elections, and which voting groups present particular problems. They expect to update their analyses constantly, given how quickly Trump can have an impact on events.

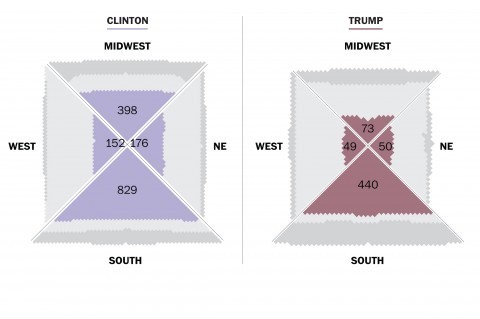

A Washington Post-ABC News poll from earlier this month showed stark divides among those backing Trump and Clinton.

Overall, the former secretary of state led 50 to 41 percent among registered voters. Trump led 49 to 40 percent among white voters, while Clinton led 73 to 19 among non-whites. Trump led by five points among men, and Clinton was up by 21 among women. Trump led by 24 points among whites without college degrees, while Clinton led by 15 among whites with degrees.

Many Republicans fear that numbers like those could doom the party to defeat in the fall, and they remain hopeful that they can stop Trump in the primaries or at a contested convention. But some Democrats worry that polling data about Trump could provide a false sense of security because voters might be reluctant to acknowledge that they intend to back him.

Party strategists and independent analysts have just begun to explore in-depth the contours of a Trump vs. Clinton election, examining in particular how the strengths and weaknesses of each candidate might affect the preferences of specific voter blocs. More difficult to assess, but no less important, is how a Trump-Clinton contest would affect turnout among those groups.

The main conclusion to date is that a Trump nomination would test theories among some Republicans about the potential strength and power of the white vote to change the electorate and give the GOP the White House. Given what is known, Trump would appear to have no choice but to center his energies on states in the industrial and upper Midwest.

The eventual conclusions of party strategists about Trump’s possible route to victory will affect critical choices for both campaigns as they decide where to invest tens of millions of dollars in resources for television ads, where to deploy their most extensive voter mobilization and get-out-the vote operations, and where the nominees will concentrate their campaign travel in the fall.

Southern dominance does not mean Trump and Clinton will win everywhere

The Midwest’s ‘blue wall’

Ruy Teixeira, a senior fellow at the progressive Center for American Progress, said Trump’s only path to victory lies in “a spike of white working-class support. . . . It’s trying to break apart the heartland part of the ‘blue wall,’ with less emphasis on the rest of the country.”

The “blue wall” is a term coined by journalist Ronald Brownstein of Atlantic Media and refers to the 18 states plus the District of Columbia that Democrats have won in the past six elections. Those states add up to 242 electoral votes, giving Democrats a foundation and therefore several combinations of other states to get to 270.

Among the 18 states that have been in Democratic hands since the 1992 election are Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Along with Ohio and Iowa, those heartland states are likely to be the most intensely contested battlegrounds in the country if a Trump-Clinton race materializes.

All those states have higher concentrations of white voters, including larger percentages of older, white working-class voters, than many of the states in faster-growing areas that Obama looked to in his two campaigns.

“If he drives big turnout increases with white voters, especially with white male voters, that has the potential to change the map,” said a veteran of Obama’s campaigns, who spoke anonymously in order to share current analysis of the fall campaign.

Steve Schmidt, a Republican strategist and veteran of past presidential campaigns, said Trump’s overall general election strength is unpredictable at this point, in part because Trump could campaign as a different candidate from the one on display throughout the primaries. But he said that what Trump has shown to date is an ability to surprise his opponents and offer crosscutting messages to draw support.

“To be successful as a Republican candidate you have to be the equivalent of a neutron bomb,” Schmidt said. “He’s a neutron bomb. Donald Trump has been disruptive in the way Uber has been disruptive in the taxi industry.”

No one expects a totally different electoral map in a Trump-Clinton campaign, given the hardening of red-blue divisions. Analysts say that nearly all the same states that have been fought over in recent elections will remain potential targets, especially at the start of the general election. Ohio, Florida and likely Virginia in particular will be fought over until the very end of the election.

On the other hand, states such as Nevada, New Mexico and possibly Colorado could see less competition unless Trump can overcome his extraordinarily high negative ratings within the Hispanic community.

The two pairs of presidential campaigns since the beginning of the 21st century proved to be remarkably static in terms of the number of battleground states and whether they voted Republican or Democratic.

Those campaigns collectively also highlight the shrinking number of truly contested states. In 2000, there were 12 such states decided by fewer than five points. By 2012, there were just four.

The 2000 and 2004 campaigns produced close finishes in the electoral college, with Republicans winning both with fewer than 290 electoral votes. The 2004 campaign was a virtual rerun of 2000, with just three states shifting to the other party: Iowa and New Mexico in the direction of the Republicans and New Hampshire to the Democrats.

Obama’s 2008 campaign changed the map, with nine states that had supported then-president George W. Bush in 2004 backing the Democratic nominee. The 2012 campaign, like 2004, reinforced the status quo. By the end of the campaign, there were only a handful of real battlegrounds and just two states shifted from 2008: Indiana and North Carolina. Both moved in the direction of the Republicans.

William Frey, a demographer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said that if Trump were to carry Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and either New Hampshire or Minnesota, he would not need some of the traditional Southern battlegrounds. Frey hastened to add that such a sweep of the Midwest appears highly unlikely. Nonetheless, he said that path through the Midwest would hold the keys to victory for Republicans if the New York businessman is their nominee.

Separate wells of support

What makes the coming campaign so intriguing is that Trump’s and Clinton’s demographic strengths are near-mirror opposites. He has drawn significant support among white working-class voters during his march toward the Republican nomination, especially white men. Clinton has drawn sizable support among minority voters, particularly African Americans, in her contest against Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

Trump’s strength among men is offset by his weakness among women. Clinton has at times struggled to attract younger women in her battle with Sanders, but few doubt she would have a significant advantage in a general election campaign against Trump.

Similarly, Trump’s support among white voters without college degrees could be offset by the prospect of similarly strong support among whites with college degrees — a growing force in the Democratic coalition.

The focus on white working-class voters will not negate the key role minority voters could play in the outcome next November. “I think that energy underneath the wings of the minority community could be as strong as it was for Barack Obama, only this time against Donald Trump,” Frey said.

One Democratic strategist said that on the basis of preliminary analysis of poll data, Trump’s vote share among Hispanics could be lower than Mitt Romney’s 27 percent share in 2012 and that his margin among African Americans could be nearly as low as Romney’s.

A recent Washington Post-Univision poll of Hispanic voters showed Trump currently doing worse than Romney, trailing Clinton in a hypothetical general election by 73 to 16 percent.

Republican Schmidt, however, warned Democrats that Trump could prove more appealing to minority voters, especially African Americans, than they assume. “He’s an asymmetric threat,” Schmidt said. “He fits into none of the conventions. He has a completely unorthodox style.”

Dan Balz is Chief Correspondent at The Washington Post where this piece was originally published. Read more at The Post: