The soaring costs of breakthrough biometric drugs -- especially for the treatment of the Hepatitis-C virus and cancer – have squeezed budgets across the board—on patients, hospitals, insurers and government healthcare programs.

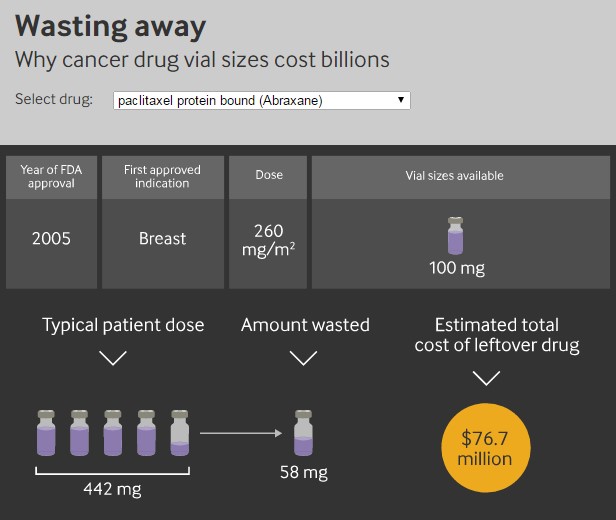

Yet far less attention has been paid to the sheer waste of those vital and pricey drugs within the U.S. health care system. A new study published Monday by a research team at New York’s Sloan Kettering Cancer Center concluded that nearly $3 billion a year is wasted by purchasing injectable cancer medicine in vials or containers that provide more medicine than is needed by a patient, with the remainder simply thrown away.

Related: Get Ready for Fireworks Over Soaring Drug Prices

Expensive drugs such as Velcade, used in the treatment of multiple myeloma, are typically injected by a nurse working in a doctor’s office or hospital and are only available in vials larger than the average dose.

In contrast to industry practices in Europe, where drugs are often sold in packages of varying sizes to meet specific needs, U.S. drug manufacturers generally follow a one-size-fits all approach that leads to extraordinary waste. As much as a third of the medicine in a vial is often discarded by nurses or doctors, or in rare instances used in the treatment of other patients.

“Even though reducing waste in healthcare is a top priority, analysts have missed the waste that can be created when expensive infused drugs are packaged containing quantities larger than the amount needed,” Dr. Peter B. Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Sloan Kettering, said in the report. This is particularly true for drugs for which dosage is based on a patient’s weight or body size and that come in single dose packages.”

Related: Ignoring Warnings, Drug Companies Hike Prices By 10 Percent

In an interview with The New York Times, which first reported on the study, Bach added, “Drug companies are quietly making billions forcing little old ladies to buy enough medicine to treat football players, and regulators have completely missed it.”

Bach and four other researchers analyzed the waste resulting from the use of the 20 top selling cancer medicines. They concluded that health care insurers paid $1.8 billion annually for discarded quantities of medicine and another $1 billion of added “markups” by doctors and hospitals. Total cost: $2.8 billion.

Under a practice dubbed “buy and bill,” doctors and hospitals purchase single dose vials of drugs and then bill insurance companies or patients when they are used, the study noted. The patient’s bill includes a percentage-based markup, which can vary widely and greatly add to the cost. Medicare and many private health care insurers charge patients as much as 20 percent in copayments, so the “buy and bill” practice can greatly add to patients’ costs.

“Although doctors and hospitals sometimes use leftover drug to treat a subsequent patient, thus reducing the amount of leftover drug for which they bill, this practice is very limited,” according to the report. “Safety standards from the US Pharmacopeia Convention permit sharing only if leftover drug is used within six hours, and only in specialized pharmacies.”

Related: Extreme Rise in Some Drug Prices Reaches a Tipping Point

In one case highlighted in the study, Takeda Pharmaceuticals sells Velcade, the cancer drug, strictly in 3.5-milligram vials that are sold for $1,034. They contain enough medicine to treat a person who is six and a half feet tall and weighs 250 pounds. If the patient is smaller – which is usually the case -- the excess is thrown out.

Part of the problem is that there is no legal or regulatory pressure on the drug industry to package their drugs more sensibly. The Food and Drug Administration, for example, said this week that it would only object to companies’ proposed vial sizes if officials believed that an excessively large amount of medicine “could lead to medication errors or safety issues due to inappropriate multiple dosing,” according to The Times.

John Rother, president and CEO of the National Coalition on Health Care, said today that the new study “documents the enormous waste from unused but extremely expensive cancer drugs, solely as a result of single dose packaging.”

“We simply can’t afford these kinds of profit-maximizing practices whenever more expensive drugs are pushing health costs to unaffordable levels,” he said.

Related: As Drug Prices Soar, Doctors Voice Outrage

The drug industry says that while there have been huge advances in treatment options for patients suffering from cancer, arthritis and Hepatitis-C, determining the right dose for patients is key to establishing the safety and effectiveness of new medicines prior to FDA approval.

“The drug development and manufacturing process for biologics, including oncology medicines, is extremely complex,” said Allyson Funk, senior communications director for Pharmaceutical Research and Manufactures of America (PhRMA). “Decisions regarding vial size are tied to a product’s initially approved dosage and labeled use, taking into account that different patients will have different needs.”

She said that vial fill size must be approved by FDA as part of the sponsor’s drug application, and that any excess volume must meet FDA standards outlined in regulations. Once a drug has received preliminary approval, a manufacturer must receive FDA approval to manufacture a new vial size, Funk said. That requires significant data and takes several months to obtain approval.

“Manufacturers are committed to working with FDA and Congress to create a more nimble regulatory approval process that enables manufacturers to modify their products as we learn about the safety, efficacy and manufacturing of new medicines from the real world clinical setting,” Funk said.