As presidential candidates focus on border walls, dirty tricks and massive increases in spending, it would be nice if, just for a moment, one of the prospective leaders of the U.S. would pause and consider the state of the nation’s finances. The economic recovery that followed the Great Recession and continued strong job growth may have combined to shield Americans from some unpleasant truths about the country’s fiscal future.

University of California-Berkeley economist Alan J. Auerbach and Brookings Institution economist William G. Gale have published a new paper that runs the numbers on the federal debt and deficit over the medium-term and long-term. Not only is the picture they paint not a pretty one but it has become dramatically worse in just the past few months.

Related: Trump-onomics Would Blow a Huge Hole in the Federal Budget

“Over the past year…the medium- and long-term fiscal outlooks have deteriorated,” they write. “Part of this is due to legislative changes, part to changes in economic and technical factors and a small part to changes in assumptions. This deterioration has happened without much fanfare and, even with a fall in projected interest rates working in the other direction, the estimated changes are large.”

For instance, looking at the same data in September, Gale and Auerbach predicted that the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio would rise from 76.6 percent to 81 percent by the year 2025 – the end of the 10-year “budget window” used for most analyses of federal spending. Revisiting the data today, they find that the projected ratio in 2025 has jumped to 91 percent.

“The trends underlying the 10–year projections are familiar,” they write. “Revenues hover at about 18 percent of GDP. Total spending is projected to rise by almost 3 percentage points of GDP—with entitlements accounting for about 1.7 percentage points of the increase and net interest for 1.9 percentage points, with discretionary spending declining by about 0.6 percent of GDP.”

Even recent signs that the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee is recalibrating its approach to normalizing interest rates doesn’t hold much promise for improvement, they found.

Related: Paul Ryan’s Three Perilous Paths to a Budget Deal

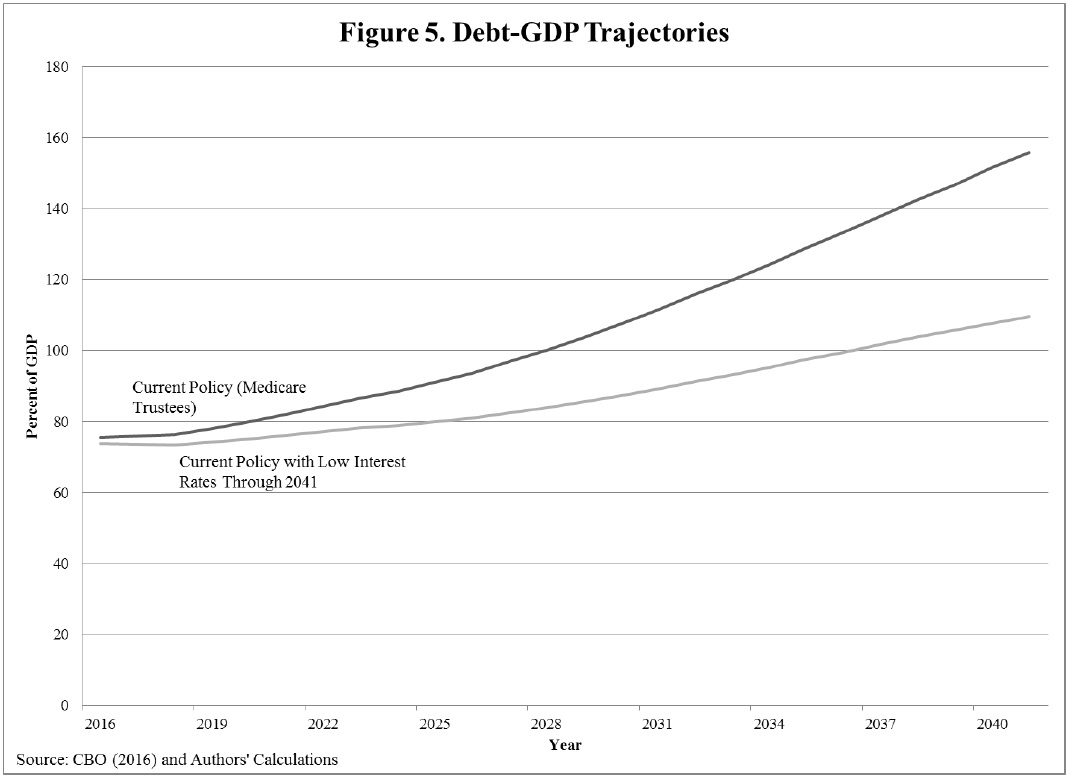

“Lower interest rates, of course, reduce net interest payments, but even with flat interest rates, the fiscal situation is headed in the wrong direction,” they said. Even after adjusting their model to consider the impact of flat interest rates for the next 25 years, the gap between projected spending and revenue needed just to maintain the status quo on debt-to-GDP is 1.8 percent of GDP.

“Thus, while low interest rates may reduce net interest payments in the near term, they do not put federal debt on a sustainable path,” Auerbach and Gale write.

Long term, the trend is even worse. “The debt-to GDP ratio rises from 93.6 percent in 2026, hits 100 percent in 2028, exceeds the previous all-time high of 106 percent in 2030, and rises to 156 percent by 2041— 25 years from now.”

Fixing the problem, they point out, will require a legislative effort unlike anything Congress has been willing or able to accomplish in recent years.

“The necessary adjustments will be large relative to those adopted under recent legislation,” they write. “Moreover, the most optimistic long-run projections already incorporate the effects of success at ‘bending the curve’ of health care cost growth, so further measures will clearly be needed.”

They conclude the paper with the note, “These changes, however, relate to the medium- and long-term deficits, not the short-term deficit.”

While innocuous at first glance, that little aside points to one of the biggest obstacles in the way of serious fiscal reform right now: in a political environment in which Congress consistently avoids acting on problems until the last possible moment, marshalling the legislative firepower necessary to solve major problems whose impact won’t be felt for years seems to be beyond the abilities of our lawmakers.