Investigators with the State Department issued a subpoena to the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea Clinton Foundation last fall seeking documents about the charity’s projects that may have required approval from the federal government during Hillary Clinton’s term as secretary of state, according to people familiar with the subpoena and written correspondence about it.

The subpoena also asked for records related to Huma Abedin, a longtime Clinton aide who for six months in 2012 was employed simultaneously by the State Department, the foundation, Clinton’s personal office, and a private consulting firm with ties to the Clintons.

The full scope and status of the inquiry, conducted by the State Department’s inspector general, were not clear from the material correspondence reviewed by The Washington Post.

A foundation representative, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss an ongoing inquiry, said the initial document request had been narrowed by investigators and that the foundation is not the focus of the probe.

At a Council on Foreign Relations event on women’s rights in New York City, Chelsea Clinton, vice chair of the Clinton Foundation, fielded questions about recent controversies over foreign donations to the foundation. (Council on Foreign Relations)

Representatives for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and Abedin also declined comment.

[How Huma Abedin operated at the center of the Clinton universe]

There is no indication that the watchdog is looking at Clinton. But as she runs for president in part by promoting her leadership of the State Department, an inquiry involving a top aide and the relationship between her agency and her family’s charity could further complicate her campaign.

For months, Clinton has wrangled with controversy over her use of a private email server, which has sparked a separate investigation by the same State Department inspector general’s office. There is also an FBI investigation into whether her system compromised national security.

Clinton was asked about the FBI investigation at a debate last week and said she was “100 percent confident” nothing would come of it. Last month, Clinton denied a Fox News report that the FBI had expanded its probe to include ties between the foundation and the State Department. She called that report “an unsourced, irresponsible” claim with “no basis.”

During the years Clinton served as secretary of state, the foundation was led by her husband, former president Bill Clinton. She joined its board after leaving office in February 2013 and helped run it until launching her White House bid in April.

Abedin served as deputy chief of staff at State starting in 2009. For the second half of 2012, she participated in the “special government employee” program that enabled her to work simultaneously in the State Department, the foundation, Hillary Clinton’s personal office and Teneo, a private consultancy with close ties to the Clintons.

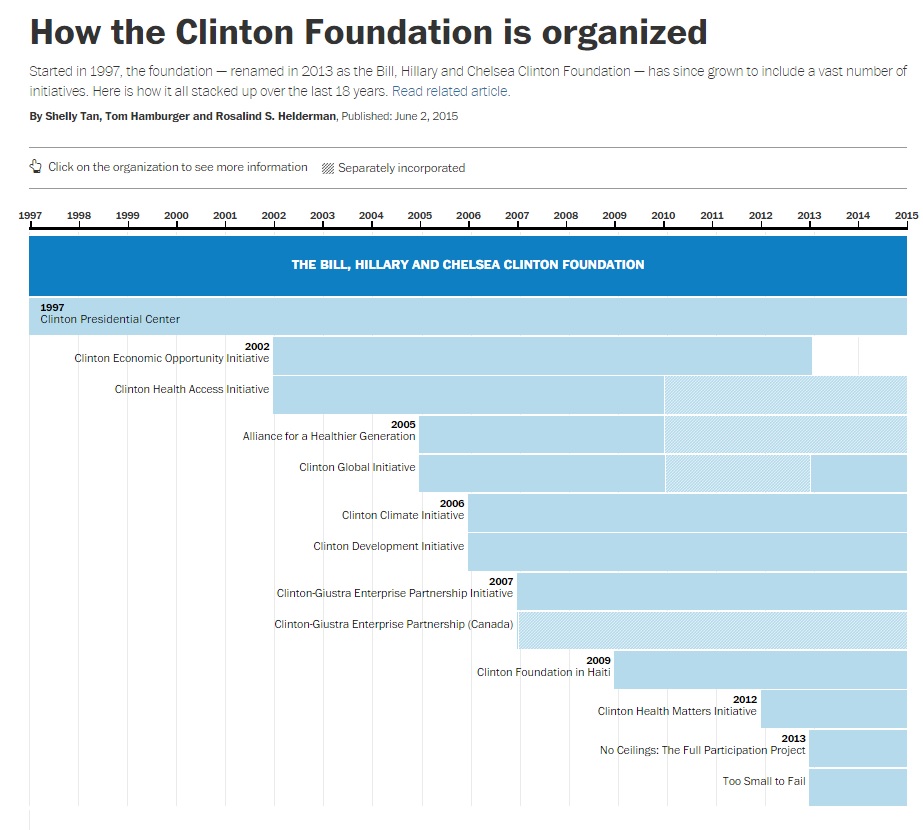

Originally founded in 1997, the foundation has since grown to include a vast number of initiatives. Here is how it all stacked up over the last 18 years.

[The inside story of how the Clintons built a $2 billion global empire]

Abedin has been a visible part of Hillary Clinton’s world since she served as an intern in the 1990s for the then-first lady while attending George Washington University. On the campaign trail, Clinton is rarely seen in public without Abedin somewhere nearby.

Republican lawmakers have alleged that foreign officials and other powerful interests with business before the U.S. government gave large donations to the Clinton Foundation to curry favor with a sitting secretary of state and a potential future president.

Both Clintons have dismissed those accusations, saying donors contributed to the $2 billion foundation to support its core missions: improving health care, education and environmental work around the world.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.), Clinton’s opponent in the Democratic primary, has largely avoided raising either issue in his campaign. Last spring, Sanders expressed concerns about the Clinton Foundation being part of a political system “dominated by money.”

Sanders has batted away questions about the email scandal, famously saying at a debate last fall that, “The American people are sick and tired of hearing about your damn emails.”

The potential consequences of the IG investigation are unclear. Unlike federal prosecutors, inspectors general have the authority to subpoena documents without seeking approval from a grand jury or a judge.

But their power is limited. They are able to obtain documents, but they cannot compel testimony. At times, IG inquiries result in criminal charges, but sometimes they lead to administrative review, civil penalties or reports that have no legal consequences.

The IG has investigated Abedin before. Last year, the watchdog concluded she was overpaid nearly $10,000 because of violations of sick leave and vacation policies, a finding that Abedin and her attorneys have contested.

Republican lawmakers, led by Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Charles E. Grassley (R-Iowa), have alleged that Abedin’s role at the center of overlapping public and private Clinton worlds created the potential for conflicts of interest.

This article originally appeared in The Washington Post. Read more at The Post