Federal Pell Grants have long helped millions of low-income college students and their families pay onerous tuition bills, especially during the depths of the Great Recession. Just last month, Congress approved a major spending package for fiscal 2016 that would preserve funding at current levels while providing a slight increase in the maximum benefit.

However, a new Gallup survey of university and college presidents published on Wednesday confirms that recipients of Pell Grants are lagging well behind other students in completing their undergraduate degrees – and that less than half of them are graduating on time.

Related: How Much Does Our Social Safety Net Cost? $742 Billion a Year and Rising

In the survey (conducted Nov. 9 through Dec.1) about half of the presidents interviewed said the undergraduate completion rate for Pell Grant recipients was less than 50 percent. Remarkably, 8 percent of the presidents said the completion rate was less than 20 percent. The completion rate was even lower at community colleges.

By comparison, the 2013 graduation rate for all first-time, full time undergraduate students pursuing a bachelor’s degree was 59 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

The disparity shouldn’t come as a big surprise. Students from low-income families frequently face many barriers to success in college, including gaps in knowledge from high school days, lack of guidance and support they need to successfully get through school, and other cultural disadvantages, according to education experts. Moreover, with the steadily mounting costs of tuition and room and board, many low income students simply have trouble making ends meet, even with Pell Grants and other government assistance.

Related: Why So Many Americans Are Trapped in ‘Deep Poverty’

Federal Pell Grants, named for the late Republican Sen. Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island, typically are awarded to undergraduate students who have not earned a BA or professional degree, and they do not have to be repaid.

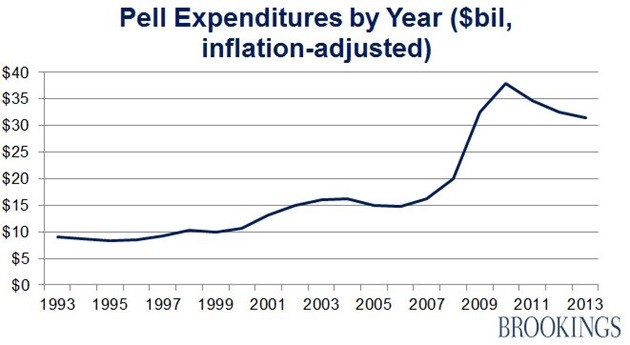

Total spending on Pell grants rose from $16.5 billion in the 2004-2005 school year to a peak of $39 billion in the midst of the Great Recession. In 2013-2014, spending dropped to $30.3 billion, according to the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. The maximum award has increased from $3,696 in 1993-94 to $5,645 today, while the average award has increased from $2,419 to $3,634.

However, experts say increases in the Pell Grant have not kept up with the increasing price of college. As a result, its purchasing power has fallen by two-thirds since 1979. According to the College Board, the average cost of tuition and fees for the 2015–2016 school year was $32,405 at private colleges and $9,410 for state residents at public colleges. For out-of-state residents attending public universities, the total was $23,893.

Related: How to Dramatically Lower the Poverty Rate Overnight

Last year, for the second consecutive year, the number of Pell recipients declined, according to a Brookings report. They dropped from a peak of 9.4 million students in the 2011-12 school cycler to 8.6 million in the 2013-14 period. There were two major factors at play that explain the decrease, according to Brookings:

- “First, enrollment at vocationally-oriented colleges (primarily community colleges and for-profit colleges) increases during recessions as displaced workers choose to receive additional training instead of trying to find a job in an awful economy,” the report stated. “When the economy gets better, more of these individuals go back to work and forgo college

- “Second, as the economy has improved, it is likely the case that some families that barely qualified for the Pell Grant during the recession no longer qualified after obtaining a better job.”