The long-suffering folks at the Tax Policy Center in Washington have spent an awful lot of time over the years explaining the unintended consequences of tax plans presented by candidates for the presidency. Earlier this year they had to show why former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee “Fair Tax” plan would be neither fair nor much of a plan. In the 2012 cycle, they had to address the problematic elements of Herman Cain’s infamous 9-9-9 plan and Newt Gingrich’s scheme to gut federal revenues.

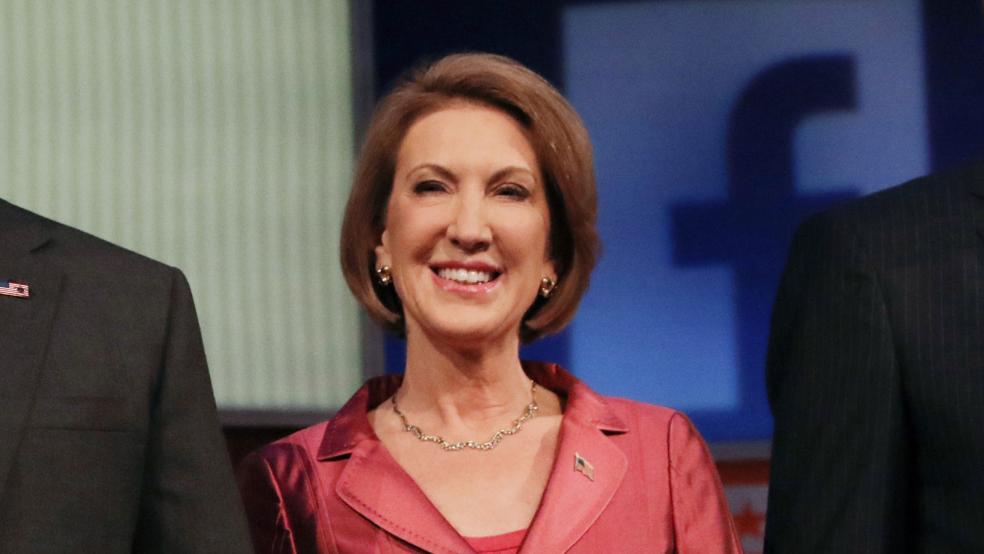

This week, at the group’s TaxVox blog, resident fellow Howard Gleckman looked into the implications of Carly Fiorina’s promise to reduce the bloated U.S. tax code to a document three pages in length.

Related: Carly Fiorina – I Don’t Do Policy Details

Fiorina has been resistant to providing details about her plan, but in advance of the GOP debate on Tuesday she linked to a Hoover Institution paper laying out a three-page re-write of the U.S. tax code.

The program is essentially a flat tax, a style of taxation in which everybody pays the same fixed percentage of their income to fund the government. Flat tax programs have enjoyed considerable public appeal for decades, largely on the strength of their simplicity and the prima facie impression that they are fair. However, there are ample reasons to believe that a flat tax program is neither simple nor fair.

The fairness issue has been addressed countless times and in countless places. Is asking someone who earns $20,000 a year to pay $3,000 in taxes while someone who earns $200,000 pays $30,000 actually fair in a sense that the majority of the American people are comfortable with? No, not really.

Gleckman, though, goes to a different and more complicated point. A three-page tax system may seem simple, but it achieves that simplicity by delegating enormous amounts of authority to the Internal Revenue Service and the Treasury Department -- something that Fiorina and her supporters might not like very much.

Related: Here’s the Problem with the GOP’s Flat Tax Proposals

“Their tax is certainly simple,” he writes. “But it is simple because it has no individual and few business deductions. Would voters be willing to swap their deductions for mortgage interest, charitable giving, state and local taxes, etc. for a three-page tax code they'd never read? I’m not so sure.”

Gleckman uses as an example sections 103 and 105 of the Hoover Institution tax plan, which applies to business income.

Section 103 defines the “cost of business inputs.”

“In general. The cost of business inputs is the actual cost of purchases of goods, services, and materials required for business purposes.”

And section 105 defines business’s taxable income.

Related: Fact Checkers Working Overtime – Top Whoppers from the GOP Debate

“Business taxable income is business receipts less the cost of business inputs, less compensation paid to employees, and less the cost of capital equipment, structures, and land.”

“Seems straight-forward enough,” Gleckman observes. “But here’s a question that might be familiar to Mrs. Fiorina from her CEO days: What does ‘actual’ cost mean? Is it market price? Or some artificially high price paid to a related party in order to maximize the deduction?

“It isn’t hard to imagine the disputes between companies and the tax collector over that one six-letter word. If it is not defined in the law (bye-bye three page code) it will inevitably be defined by regulation, litigation, and other interpretations. Indeed, firms and the IRS have been battling over this very issue, called transfer pricing, for decades.”

As Gleckman points out, those questions would ultimately have to be decided via rulings from the IRS and by federal courts.

Related: How Trump Carson and Cruz Turned Republican Voters Against the GOP

In the end, after regulatory rulemaking and court challenges, Gleckman notes, “It would take thousands of pages of [regulations] for the IRS to enforce a short -- but vague — statute, for compliant taxpayers to understand their obligations, and to prevent abuse by those who would cheat.

“Fiorina might keep her pristine three-page tax code. But the price she’d pay is granting vast new power to regulators and judges. I’m not sure she, or many GOP voters, would think that’s such a great idea.”