President Obama’s decision to expand the U.S. war effort in Iraq and Syria is a reflection of the conflicting pressures on a commander in chief who doubts that military force alone can end the conflicts in those countries, but who also feels compelled to act in the face of a humanitarian catastrophe and a growing threat to the United States.

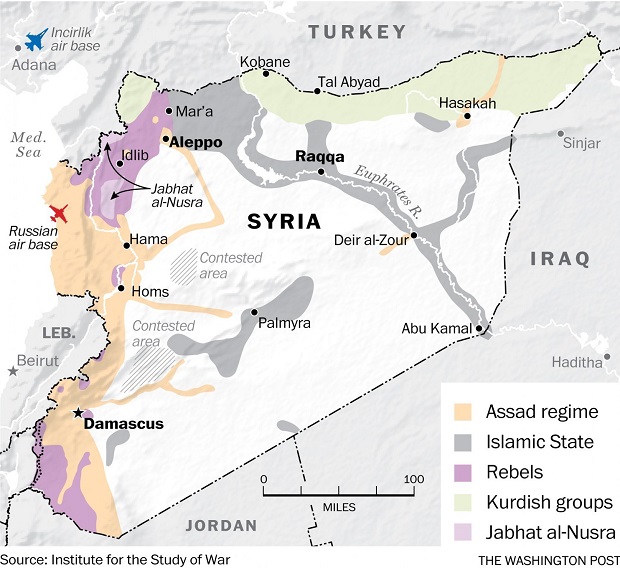

The president on Friday said that he was sending about 50 Special Operations troops to northern Syria to work with Kurdish and Arab fighters battling the Islamic State. The deployment, though small, marks the first full-time deployment of U.S. forces to the dangerous and chaotic country.

Related: How Putin Put Obama in a Bind on Syria

The troops will be accompanied by more U.S. attack planes, based across the border in Turkey, and plans for more joint raids — led by Iraqi counterterrorism forces — to capture and kill Islamic State leaders.

The troops, planes and plans for more raids represent an “intensification” of the president’s existing strategy, said senior administration officials. Few of those officials, however, suggested that the moves would be enough to break open the stalemated conflict or produce sudden battlefield gains.

“This is a very complex battle space, and we’re not directly involved in the way we’ve been in the past,” said a senior administration official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

The White House said President Obama plans to deploy a small number of special operations troops to Syria. When asked about the number of troops, White House press secretary Josh Earnest said, “The less-than-50 number is accurate.” (Reuters)

Without a clear overarching strategy to resolve the conflict, “we’re looking at things in a granular way,” the official said. The goal, for now, is simply to incrementally reinforce those areas that are working and abandon initiatives that are not.

Obama began his second term by ending one war in Iraq and pledging to bring home America’s ground troops from a second in Afghanistan. To that end, he set hard limits on U.S. deployments and firm timeframes for the withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Related: Here’s the U.S. Missile That’s Altering the Battlefield in Syria

Before deploying forces, Obama would regularly demand that his commanders explain the “theory of the case” behind the moves. The phrase is evocative of the president’s legal training and his deep skepticism that U.S. military power can bring lasting change to broken societies. He wanted assurances that the operations would work as intended as well as coherent explanations of how and when they would end.

As he nears the end of his presidency, Obama faces the prospect that he will leave office with ground forces deployed to three combat zones.

Last month, the president said he would keep 5,500 ground troops in Afghanistan to advise struggling Afghan army and to pursue the remnants of al-Qaeda. In Iraq and Syria, the president has incrementally boosted the U.S. force, beginning an initial deployment of several hundred troops to Iraq in 2014, after Iraqi army forces in Mosul were overrun by Islamic State fighters. The president sent 450 more American trainers and advisers after Iraqi forces were routed at Ramadi by a much smaller Islamic State force in the spring.

Those forces were supposed to work with the Iraqi army and local tribal fighters to plan an offensive on Ramadi that has largely stalled. “We have four axes converging on Ramadi, and on any given day, none of them makes any movement at all,” said a senior U.S. official involved in the war planning.

Related: Here's Why Obama Is Refusing to Meet with Russia to Discuss Syria

Frustrated with the lack of progress, Obama in July made a rare visit to the Pentagon to push Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter and his top commanders for options to increase the intensity of U.S. military operations without putting U.S. troops in a direct combat role.

More ambitious and costly measures such as no-fly zones or buffer zones that would require tens of thousands of ground troops to effectively protect civilians were rejected. Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Rodham Clinton has said that she favors a no-fly zone in Syria. Other riskier proposals, such as the introduction of Apache helicopters or combat advisers who would move closer to the front lines and call in airstrikes or bolster the Iraqi attack on Ramadi, weren’t explicitly rejected but were deemed unnecessary for now.

The president’s final decision balanced his desire for the United States do more with his determination to keep American forces from being pulled too deeply into conflicts in which U.S. effectiveness was limited or where there were no clear military solutions.

The 50 Special Operations troops and the new attack planes heading to Syria and Turkey will bolster Kurdish and Syrian Arab forces that were able to make surprising gains over the summer with the backing of U.S. warplanes.

“The success in northern Syria wasn’t the result of any strategic planning,” said a senior defense official who tracks operations in the region. “Really, it was an opportunity that fell into our laps.”

Syrian Arab and Kurdish forces have fought to within 30 miles of Raqqa, the Islamic State’s de facto capital. With additional American help, U.S. officials said the fighters could isolate the city, cutting its supply lines running up to the Syrian border.

Related: Obama’s Failure in Syria Now Extends to Turkey

Over the longer term, U.S. officials said that a loose coalition of Syrian Arab, Turkmen and Kurdish fighters might be able to dislodge the Islamic State from a 68-mile stretch of the border, creating a space where refugees can find haven. The hope is that the coalition can also begin to provide some level of governance and take part in diplomatic negotiations to replace Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

But even the most optimistic U.S. officials said such an outcome could take years.

In the near term, administration officials expressed cautious optimism that the combination of more U.S. air power, a bigger Iraqi push against Islamic State forces in Ramadi along with Kurdish and Syrian Arab efforts in Raqqa and along the border could shift the momentum on the battlefield.

So far, it’s a strategy that hasn’t draw much support in Washington. Republicans and some Democrats, who have been pressing Obama to do more, criticized the president’s caution.

“His incremental step-by-step approach is an effort to manage risk and keep tight reins on the mission, but ultimately it could mean that the whole is less than the sum of its parts,” said Michele Flournoy, the chief executive officer of the Center for a New American Security, who was among Obama’s top choices to be defense secretary last year before Carter was selected.

Related: U.S. Special Forces Are Heading to Syria

Flournoy said the addition of U.S. air controllers to call in airstrikes and Apache helicopters, combined with the measures the president is already taking, could accelerate gains on the battlefield.

“If he took these actions all at once, it could have a greater impact,” she said.

Some liberal Democrats described the president’s moves as a slippery slope to a deeper U.S. commitment. Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) called the president’s announcement last week the “latest in a series of alarming signs that the U.S. war against ISIS will continue to accelerate in the absence of congressional action.”

White House officials, meanwhile, described the president’s moves as the product of hard lessons learned on a complicated and chaotic battlefield. “We always envisioned this as a three-year campaign,” the senior U.S. official said. “In year one we learned some of our local partners did well and others didn’t. So we are doubling down on those who did well.”

This article was published originally in The Washington Post. Read More in The Post: