Much has been made about the impressive gains in efficiency and productivity in the shale patch, as new drilling techniques squeeze ever more oil and gas out of new wells. But the limits to such an approach are becoming increasingly visible. The U.S. shale revolution is running out of steam.

The collapse of oil prices has forced drillers to become more efficient, adding more wells per well pad, drilling longer laterals, adding more sand per frac job, etc. That allowed companies to continue to post gains in output despite using fewer and fewer rigs.

However, the efficiency gains may have been illusory, or at best, incremental progress instead of revolutionary change. Rather than huge innovations in drilling performance, companies were likely just trimming down on staff, squeezing suppliers, and drilling in the best spots – perhaps all sensible stuff for companies dealing with shrinking revenues, but nothing to suggest that drilling has leaped to a new level of efficiency. Reuters outlined this phenomenon in detail in a greatOctober 21 article.

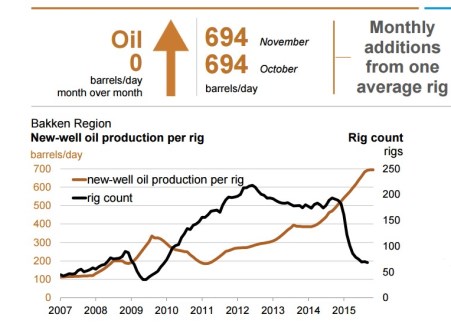

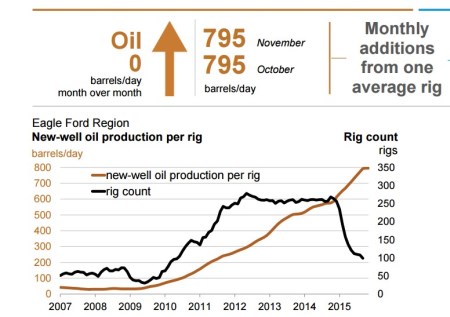

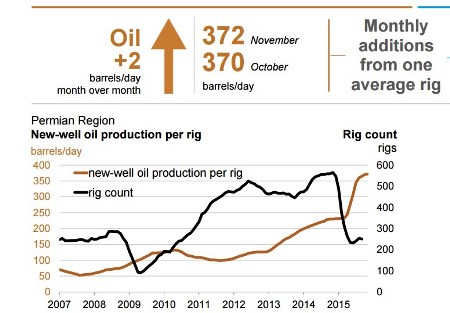

For evidence that the productivity gains have run their course, take a look at the latest Drilling Productivity Report from the EIA. Production gains from new rigs – which have increased steadily over the past three years – have run into a wall in the major U.S. shale basins. Drillers are starting to run out of ways to squeeze more oil out of wells from their rigs. Take a look at the below charts, which show drilling productivity flat lining in the Bakken, the Eagle Ford, and the Permian.

Related: Geothermal Energy Could Soon Stage A Coup In Oil And Gas

For oil companies to add new production at this point it would require hiring new workers and new rigs and simply expanding the drilling footprint. That is something that few companies are doing because of low prices. In fact, most exploration companies are doing the opposite – rig counts continue to decline and the layoffs continue to mount.

Related: Bargain Hunters Stop The Freefall In Oil Prices, For Now

With productivity at the end of the road, and new drilling not taking place, absolute production levels are in decline. The EIA expects U.S. shale basins to lose 93,000 barrels per day between October and November, led by a 71,000 barrel-per-day loss from the Eagle Ford in South Texas.

The losses are occurring because of the huge drop off in shale production that new wells suffer from almost immediately after going into service. Take a look at the chart below that shows the “legacy” production from the Eagle Ford (i.e., old wells that are declining), which is overwhelming all the new production. The net result is a fall in oil output in South Texas.

As time goes on, that legacy figure will continue to swell, and the amount of oil flowing from new wells will decline. This is exactly why overall U.S. oil production is declining and will continue to decline through next year. The only way to turn things around is for drillers to drill new wells.

Related: Is The Oil And Gas Fire Sale About To Start?

Refining Hurt Too

The fall in U.S. oil production is starting to affect the downstream sector. Refineries have performed well from the downturn in oil prices, as they use crude as an input to produce refined products such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and more. Integrated oil companies, such as the oil majors, saw their losses shielded from an upturn in refining profits.

But now that oil production is falling – down from a peak of 9.6 million barrels per day to somewhere around 9.1 mb/d currently – refining margins are shrinking. Refineries benefited from a glut of crude sloshing around in the U.S., unable to be exported because of the export ban. WTI crude, a benchmark for U.S. oil, began trading at a discount relative to international benchmarks such as Brent. Refiners would buy cheap WTI and process it into refined products and sell them abroad at prices more closely correlated with Brent, pocketing a nice profit.

However, the fall in upstream production has trimmed some of that excess crude. As a result, the WTI-Brent discount has narrowed and so have refining margins. Bloomberg reported that profits from refining crude into gasoline recently hit its lowest level since 2010. Citigroup downgraded a series of refining stocks this week as the outlook for the downstream sector worsens.

For integrated oil companies, this development isn’t great either. Oil prices are still down, production is down, and now refining margins are down.

By James Stafford of Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com: