Automakers Are Having a Record Year, but Here’s a Trend that Should Worry Them

U.S. auto sales closed out the summer on a positive note, topping estimates and casting some rosy light on the health of the American consumer. Recording its best August since 2003, the auto industry is on pace to sell 17.8 vehicles in 2015, well ahead of expectations of 17.3 million. If the numbers hold up, 2015 will be the best year ever for U.S. auto sales, beating the 17.4 million mark set in 2000.

The general consensus is that auto industry is in pretty good shape these days. Gas prices and interest rates are low, boosting the market for cars and light trucks. More than 2 million jobs were added to the U.S. economy in the past year, and more jobs is usually good news for auto sales. The unemployment rate has been trending lower for five years, sitting at a relatively healthy 5.3 percent in July.

Related: What's Next for Oil Prices? Look Out Below!

As with any statistic, though, there’s more than one way to look at the situation. Sure, auto sales are climbing as the economy gets stronger and more Americans hit their local car dealers’ lots. At least to some degree, though, higher auto sales should be expected just as a result of U.S. population growth. And those rising monthly sales figures are masking a continuing trend that is more worrisome for the auto industry: per capita auto sales are still in a long-term decline, even including the solid growth the industry has seen since the end of the recession. Doug Short at Advisor Perspectives did the math and made a graph:

According to Short’s analysis, the peak year for per capita auto sales in the U.S. was 1978. As the red line in the graph shows, the trend is negative since then.

In the graph, per capita auto sales in January, 1976, were defined as 100; the readings in the index since then are relative to that 1976 sales level. As you can see, the index moves higher until August of 1978, when per capita auto sales were up nearly 20 percent over 1976. Since then, per capita auto sales have fallen, reaching a low in 2009 that was nearly 50 percent lower than 1976. Since 2009, per capita auto sales have risen nicely, but are still more than 15 percent below peak.

What could explain the negative trend? Two factors come to mind. First, demographics. It has been widely reported that the millennial generation is less interested in owning cars for a variety of reasons, ranging from a weak economy to a cultural shift away from suburban life. However, the data on millennial car purchases is ambiguous; recently, millennials have started buying cars in volumes that look a lot like their elders. And even if millennials are less interested in buying cars, their preferences can’t explain a shift that began in the 1970s, before they were born.

Related: U.S. Companies Are Dying Faster Than Ever

The other factor that may explain the trend is income inequality. A study of car ownership by the Carnegie Foundation found that countries with higher income inequality have fewer cars per capita. The logic is simple: As more income is claimed by the wealthy, there’s less to go around for everyone else. And that means there’s less money for middle and lower income groups to buy and maintain automobiles, among other things.

Here’s a chart of the Gini index for the U.S. since 1947. (The Gini Index is a widely-used measure of income inequality. A higher Gini number means higher inequality.) Note that the Gini reading started climbing in the late ‘70s – the same time when per capita car ownership in the U.S. began to fall.

This chart tells us, not for the first time, that the U.S. has experienced more income inequality since the 1970s. Combined with the per capita auto sales data above, it suggests that as the rich have gotten richer and everyone else has struggled to keep up, car ownership has suffered. Although this is by no means proof of the relationship between income inequality and per capita car ownership over the last 40 years, it hints at an interesting theory – and suggests that the auto industry has good reason to be concerned about growing inequality in the U.S.

Top Reads From The Fiscal Times:

- 6 Reasons Gas Prices Could Fall Below $2 a Gallon

- Hoping for a Raise? Here’s How Much Most People Are Getting

- What the U.S. Must Do to Avoid Another Financial Crisis

Tax Refunds Rebound

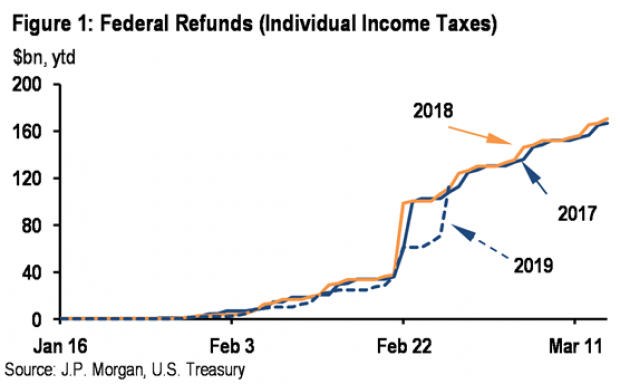

Smaller refunds in the first few weeks of the current tax season were shaping up to be a political problem for Republicans, but new data from the IRS shows that the value of refund checks has snapped back and is now running 1.3 percent higher than last year. The average refund through February 23 last year was $3,103, while the average refund through February 22 of 2019 was $3,143 – a difference of $40. The chart below from J.P. Morgan shows how refunds performed over the last 3 years.

Number of the Day: $22 Trillion

The total national debt surpassed $22 trillion on Monday. Total public debt outstanding reached $22,012,840,891,685.32, to be exact. That figure is up by more than $1.3 trillion over the past 12 months and by more than $2 trillion since President Trump took office.

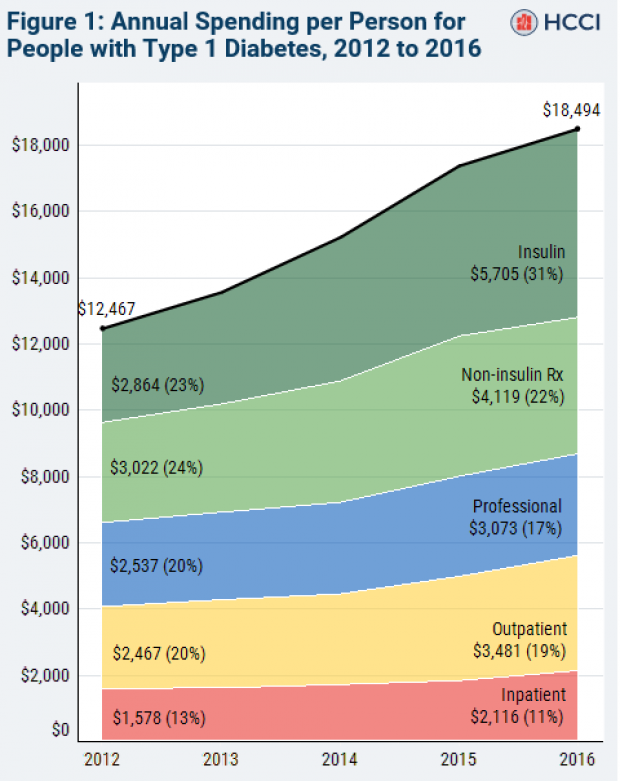

Chart of the Week: The Soaring Cost of Insulin

The cost of insulin used to treat Type 1 diabetes nearly doubled between 2012 and 2016, according to an analysis released this week by the Health Care Cost Institute. Researchers found that the average point-of-sale price increased “from $7.80 a day in 2012 to $15 a day in 2016 for someone using an average amount of insulin (60 units per day).” Annual spending per person on insulin rose from $2,864 to $5,705 over the five-year period. And by 2016, insulin costs accounted for nearly a third of all heath care spending for those with Type 1 diabetes (see the chart below), which rose from $12,467 in 2012 to $18,494.

Chart of the Day: Shutdown Hits Like a Hurricane

The partial government shutdown has hit the economy like a hurricane – and not just metaphorically. Analysts at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget said Tuesday that the shutdown has now cost the economy about $26 billion, close to the average cost of $27 billion per hurricane calculated by the Congressional Budget Office for storms striking the U.S. between 2000 and 2015. From an economic point of view, it’s basically “a self-imposed natural disaster,” CRFB said.

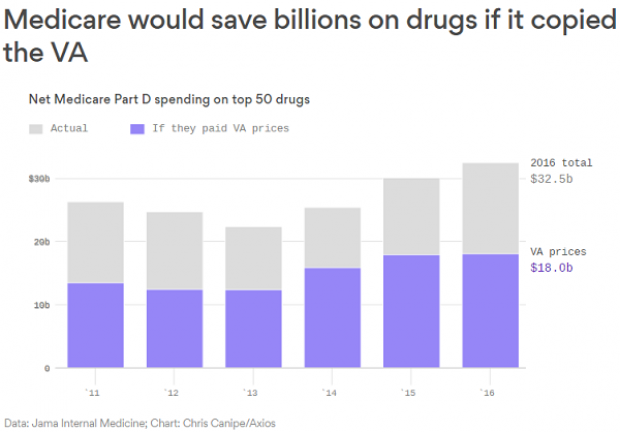

Chart of the Week: Lowering Medicare Drug Prices

The U.S. could save billions of dollars a year if Medicare were empowered to negotiate drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies, according to a paper published by JAMA Internal Medicine earlier this week. Researchers compared the prices of the top 50 oral drugs in Medicare Part D to the prices for the same drugs at the Department of Veterans Affairs, which negotiates its own prices and uses a national formulary. They found that Medicare’s total spending was much higher than it would have been with VA pricing.

In 2016, for example, Medicare Part D spent $32.5 billion on the top 50 drugs but would have spent $18 billion if VA prices were in effect – or roughly 45 percent less. And the savings would likely be larger still, Axios’s Bob Herman said, since the study did not consider high-cost injectable drugs such as insulin.