As members of Congress debate how to pay for a number of initiatives that are expected to come before them this summer — particularly the pending expiration of the Highway Trust Fund — the idea of imposing a small tax on financial transactions will almost certainly be brought up repeatedly. Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, two candidates for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, have also called for such a tax.

Calls for introducing a Financial Transaction Tax have grown since the financial crisis and the Great Recession, and the concept has been just below the surface of many recent discussions of tax reform in the U.S. But before any debate over the idea heats up, a new study from the Tax Policy Center busts some of the myths surrounding the tax and comes up with a bottom line finding that, if properly implemented, it could raise $50 billion a year without seriously affecting the operation of the financial markets.

The study, by Leonard E. Burman, William G. Gale, Sarah Gault, Bryan Kim, Jim Nunns and Steven Rosenthal, begins by reminding readers that far from being a major innovation, a tax on financial transactions was actually the norm in the U.S. for much of the country’s history.

Related: Smart Tax Reform Has to Account for This Massive Change

“The United States imposed a nontrivial stock transactions tax from 1914 to 1965, as did New York State from 1905 to 1981,” they write. “An extremely small securities transfer tax currently funds the Securities and Exchange Commission.”

Many countries already have similar taxes in place, and 11 European countries are working to implement a joint system of financial transaction taxes in January of next year, which will in theory mesh with an existing FTT in France.

Those in favor of the tax claim that it could raise a large amount of money and at the same time reduce market volatility by making speculative activity more costly — potentially driving what some advocates call unproductive speculators out of the market. In the wake of the financial crisis, rightly or wrongly, some also see a sort of rough justice in squeezing the financial sector for more tax revenue.

Opponents say it would create inefficiencies in the market by encouraging investors to engage in tax avoidance schemes, and that rather than being spread evenly across the financial sector, it would hit certain portions where transactions are more frequent much harder than others. They also claim that it would cut down on productive and unproductive trading alike, reducing liquidity, increasing the cost of capital and discouraging investment. Opponents also dispute the claim that the tax would fall mostly on the rich, arguing that middle class investors in mutual funds would bear a disproportionate share of the burden.

Related: Americans Spend More on Taxes Than on Food, Clothing and Shelter

The Tax Policy Center Study examines some of the claims on both sides of the debate. One of the clearest conclusions of the paper is that while an FTT, properly designed, could bring billions in revenue to the U.S. Treasury, it is no cure-all for the country’s budget problems. The researchers determined that the maximum an FTT could extract from the financial markets without doing more harm than good would be in the neighborhood of $50 billion a year — a large sum in most contexts but a small fraction of the $3.5 trillion federal budget.

The reason for that limit is that traders are sensitive to price increases and would curtail their buying and selling as the FTT rate rose. The $50 billion figure is based on a roughly 0.1 percent tax rate, but if the rate jumped to 0.5 percent, the authors estimate that trading levels would fall to the point that less revenue would be raised.

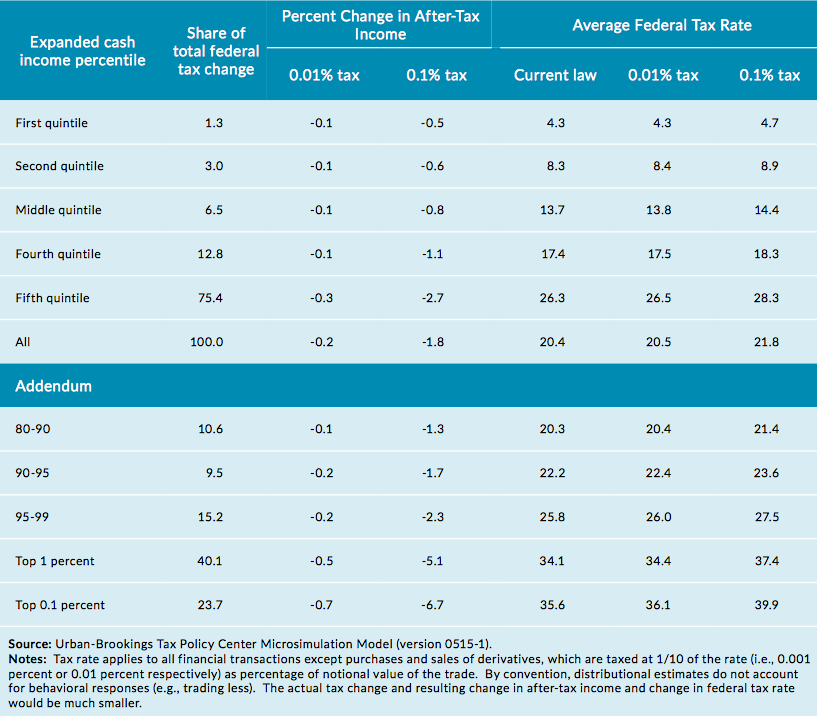

But while an FTT might not raise as much revenue as some hope, it would raise most of it from the very wealthy, meaning that it would be highly progressive.

In the end, the Tax Policy Center authors seem to suggest that, for right now at least, an FTT shouldn’t be adopted without more research. “The key question is whether an FTT is the best option relative to other potential taxes in terms of economic costs and benefits, fairness, and costs of administration and compliance,” they write. The answer is, at present, unclear.

Related: The 7 Taxes We Hate the Most

As for the idea that the FTT imposes a just punishment on the financial sector for its role in the financial crisis and can be an effective deterrent for future misbehavior, the authors say there are better choices.

“Over the long term, it appears poorly targeted at the kinds of financial-sector excesses that led to the Great Recession,” they find. “If the goal is to have the financial sector pay the costs of its past or future bailouts and compensate the rest of the country for the costs imposed in the financial crisis, [a different tax scheme] might be more effective and less distortionary.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: