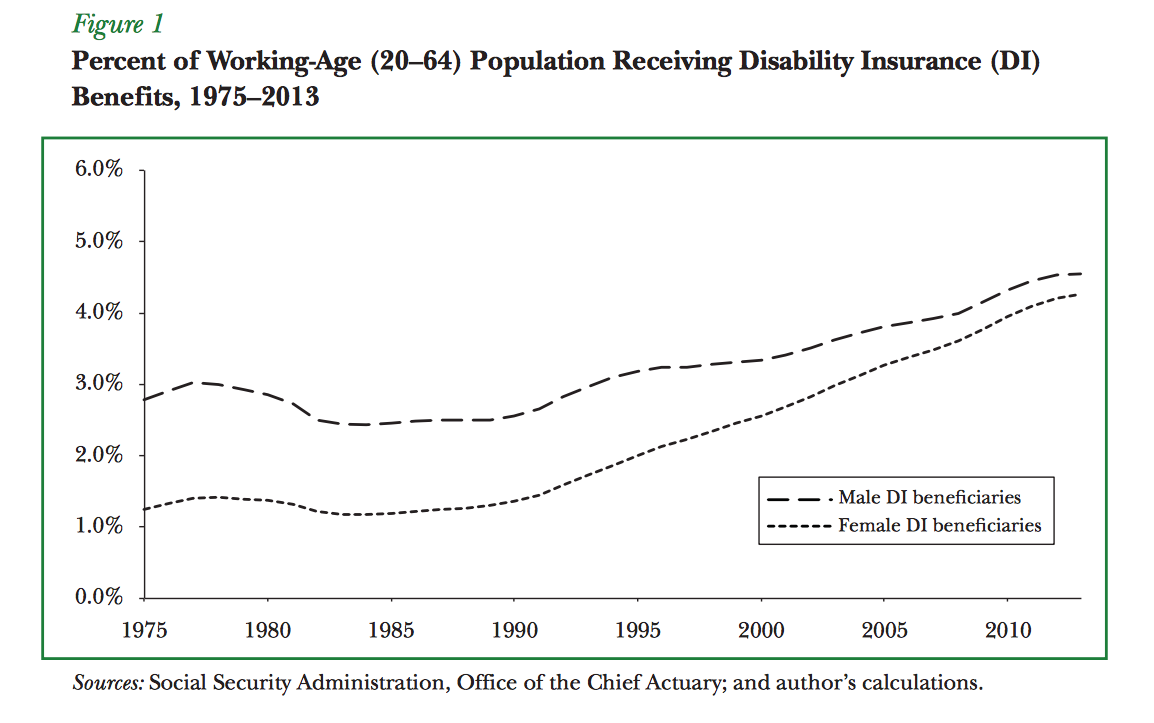

In the years following the Great Recession, social scientists observed a steady increase in the percentage of the working population claiming federal disability insurance benefits. This led to concern that the program was being used as an alternative form of unemployment insurance – people unable or unwilling to find work, the theory went, were presenting themselves as disabled in order to claim additional financial support from the government.

Analyses of enrollment data have demonstrated that relative to other government programs, there is a high rate of fraud in disability insurance claims. A report last year by Government Accountability Office said the Social Security Administration was vulnerable to fraud, especially false claims submitted by unscrupulous doctors.

Related: Obama Juggles the Numbers to Save Social Security Disability Benefits

"While the full extent and nature of physician-assisted fraud is difficult to measure, each fraudulent claim allowed by SSA has the potential to cost the government several hundred thousand dollars over the life of the claimant and places an additional financial burden on these programs at a time when SSA estimates that its disability trust fund will be depleted and unable to pay full benefits to individuals starting in 2016," the report said.

However, a new paper published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives finds that in the years leading up to the Great Recession the rate of disability claims was already on the way up, and was driven not primarily by fraud, but by a complex mix of demographic, economic, and cultural change -- most notably a 1984 change in the law that made it easier to qualify in the first place.

With the Social Security Disability Insurance fund expected to run out of money in 2016, author Jeffrey B. Liebman, a professor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, offers a number of areas of potential reform that lawmakers should consider when they move to shore up the program, as seems inevitable.

Related: New Evidence That Disability Fraud Costs Billions

“By international standards, US spending on disability benefits relative to GDP remains low,” he writes. “The OECD provides data on total public expenditures on disability and sickness cash benefits for its member countries. In 2011, average spending in the OECD on these benefits was 1.9 percent of GDP. In the US, it was 1.3 percent of GDP….Despite the relatively modest US expenditures on these programs, there is a strong case for treating the coming exhaustion of the Disability Insurance trust fund as an opportunity for improving the US Disability Insurance system.”

Liebman notes that in a given year only about 1 percent of DI recipients leave the rolls due to an improvement in health, and suggests that improving incentives to return to work could increase that number.

“The current disability benefit package essentially provides lifetime cash benefits and health insurance in exchange for a promise never to do substantial work again,” he writes. Because doing any significant amount of work triggers elimination of benefits, workers have a disincentive to reenter the workforce. “A sizable portion of the disabled beneficiary population might be better off with assistance that helps them return to employment,” Liebman says.

Related: Medicare Advantage Fraud – Heat on the Justice Department to Investigate

He notes that employers often have an incentive to push workers into disability rather than accommodating them with changes to the work environment that might allow them to remain. He points out that others have suggested a system in which employers are required to offer disability insurance that covers the first two years of disability.

“Because employers would be charged different rates by the private insurance companies depending on the benefit claims of their employees, employers would have an incentive to find ways to keep their disabled workers employed.”

Finally, he proposes three pilot programs: one that would provide businesses a tax credit if they can reduce disability claims by a certain amount, another that would offer disability applicants short-term financial assistance, healthcare assistance, and job training as an alternative to signing up for DI, and a third that would allow states to reconfigure benefit programs in an effort to better identify individuals at risk of needing lifetime DI and proactively intervene.

Looking at the work ahead for lawmakers, Liebman wrote, “It will take additional creative economic thinking in the next few years to design and evaluate the research and pilot projects that are needed to provide the evidence to guide broader reforms.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times