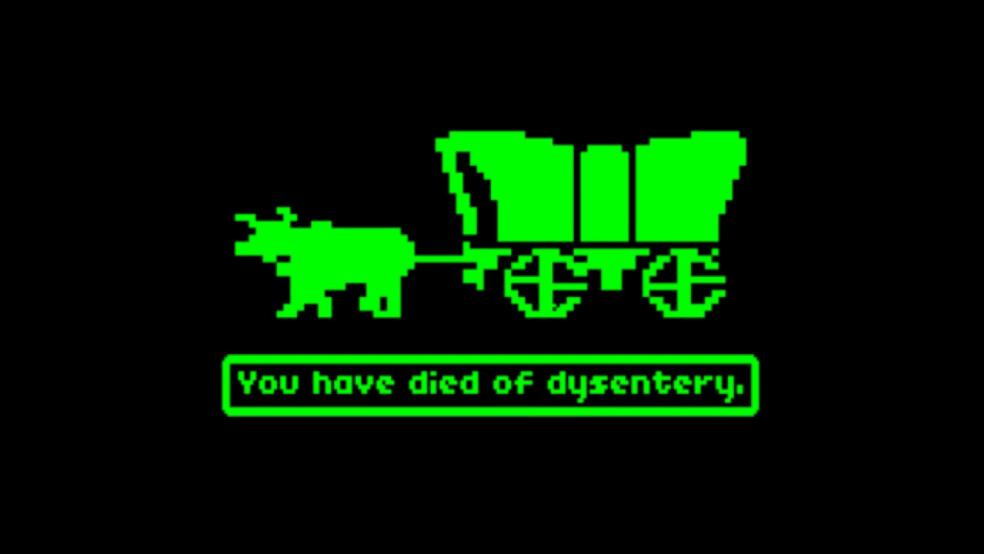

Your oxen have drowned. You have a snakebite. You have died of dysentery.

In a bygone age, all of these messages glowed on computer lab Apple IIs in blocky green text, while middle school history students clawed at their hair in frustration. They were part of a hit game called Oregon Trail that was made in just two weeks by a student teacher, Don Rawitsch, and was later funded by the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. It was intended to impress upon students the harsh realities of life along the pioneer trail.

And boy, did it. Since it was developed in the 1970s, Oregon Trail has left a formidable legacy in America’s classrooms, clocking an impressive 65 million sales across its multitudinous platforms and versions. Most millennials will have fond memories of playing it, and, thanks to ports to the iPhone and Android, many still do. As an educational tool, it was a success.

Related: Video Game Changers — 21 Titles That Rocked the Industry

Given that early triumph, it seems strange that even as video games have accelerated at a breakneck pace — constantly adding polygons, exploring virtual reality and breaking new grounds in storyline and narrative — video games in the classroom are largely still limited to the kid in the back row playing on a smuggled-in Nintendo DS.

Regular video games have long been acknowledged to have some benefits in developmental education. A study from 2002 cited games as advantageous to developing individuals in a host of ways, from improving self-confidence and social skills to honing problem-solving abilities and underlining the importance of goal-setting. Some researchers argue that high-octane, action-oriented video games may enhance learning speed and decision-making.

As video games become increasingly popular — almost 60 percent of people now play, be it crushing candies or killing aliens — they have also become more accepted on college and high school campuses. Robert Morris University in Chicago and the University of Pikeville in Kentucky now offer scholarships to students playing the competitive video game League of Legends. U.C. Berkeley offers a class dedicated to the study of the strategy of Starcraft.

Related: Yes, Video Games Really Are Ruining Your Kid’s Social Skills

Whatever skills players might gain from Portal 2 or Starcraft, though, those games clearly aren’t replacements for textbooks. Educating students with video games requires more specialized tools. Sensing a gap in the market, several companies are looking to provide those tools.

One such company is Muzzy Lane, which has made about 13 games, all across the educational spectrum. There’s a Candy Crush-style iPhone game in which players match algebraic functions. There’s a civics game that takes players through the career of a freshman senator. Muzzy Lane’s latest offering is Making History: The Great War, a World War I strategy/simulation game that is currently being used in a Harvard class. At the moment, many of the company’s games are sold through textbook manufacturer McGraw-Hill and are styled as an optional enhancement to the lesson plan.

“Since so many people are playing games in their free time, they translate well to the classroom,” Chris Parsons, the product manager of Muzzy Lane, said last week at the company’s booth at the PAX East gaming confab. “It’s a way of presenting information in a relatable format, and that adds to the classroom experience.”

Related: Video Games Could Be Coming to Vegas Casinos

The games have made enough of a splash that a least one major charitable institution has taken note: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation gave Muzzy Lane a research grant to create some proof-of-concept educational games that are aimed at low-income students.

“I’m certain that these games will make it on to the curricular level at some point,” said Parsons as we were finishing up our chat. “So many people play games now, it’s inevitable.”

Surrounded on both sides by a crowd of tens of thousands of PAX attendees, it was kind of hard not to see his point.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: