If you’re looking for a job, I have some good news. You have 5 million to choose from. That’s right. America currently has 5 million vacancies waiting to be filled.

That’s more job openings than we’ve had at any time since 2001. It’s even true in proportional terms: If we account for population growth and express vacancies as a share of the labor force, the current job openings rate of 3.2 percent is still at a post-2001 high. It’s a pretty good time to be a job seeker. Or at least it could be — if you know where to look for jobs and you have the skills employers are seeking.

Related: The 10 Best Cities For Job Seekers

So where are these 5 million jobs hiding? And, more to the point, why haven’t you heard more about this bounty of opportunities? The answer, it turns out, has everything to do with a little-discussed bias in popular conversations about the labor market.

Friday morning, we’ll get the latest unemployment numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As usual, the jobs report will be greeted with much fanfare, as the statistics are sliced and diced in more ways than a craps game on a hibachi grill. But that unemployment entrée, however artfully it may be spiced and sautéed, gives us only half the meal.

Why’s that? Well, unemployment is a measure of “excess supply.” It tells us what portion of workers want jobs but don’t have them. Because trends in unemployment tend to track closely with the overall state of the economy, it is a useful shorthand for describing the health of the labor market.

There’s more to the labor market than workers wanting jobs, though. Like a coin, markets have two sides; the counterweight to supply is demand. And that’s exactly what job openings give us — a measure of “excess demand.” Openings are to employers what unemployment is to employees: unfulfilled desires. It’s only by putting the two together that we can accurately understand the labor market’s vitality.

Related: The Dark Shadow Hanging Over the Economic Recovery

Think of it this way. In December, 8.7 million Americans were counted as officially unemployed. That’s a big number, but one that seems a bit more manageable when you recognize America’s 5 million vacancies are enough to provide more than half of them with jobs.

Incidentally, the data on job openings is no state secret—they’re released every month by the BLS in the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). But they often get much less attention that do their spotlight-basking supply-side counterparts.

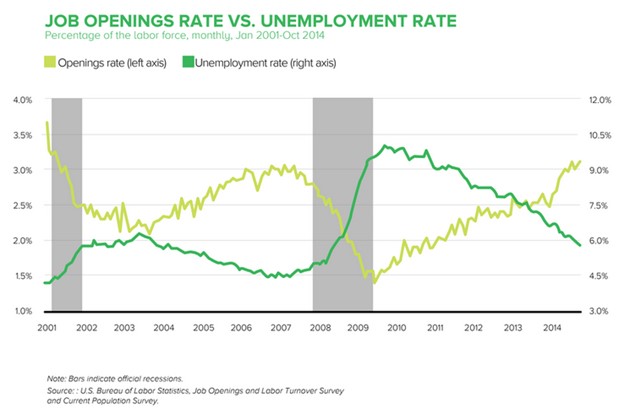

The figure below, reproduced from the third installment of my Working Paper Series for The Century Foundation, released today, shows the trends in the job openings and unemployment rates since 2001. As you might expect, the two usually move in opposite directions: When openings fall, as they did during the Great Recession, unemployment rises, and vice versa. The second thing to note is that a healthy economy the size of the U.S. will always have millions of job openings and millions of unemployed. That’s because it takes time for job seekers and job recruiters to find each other. People are constantly changing jobs, businesses are constantly opening and closing, and these processes do not happen instantaneously.

The present situation, however, presents something of a puzzle. The job openings rate has already surpassed its pre-recession benchmark. The same can’t be said of unemployment. Although the unemployment rate has fallen steadily in recent months, to 5.6 percent, it’s still noticeably above its 4.6 percent average from 2007 — and that’s despite a major drop in the labor force participation rate. In other words, based on historical patterns, we’d expect the level of job openings we see today to produce a lower unemployment rate than the one we have. The job market should be better than it is.

Related: 3 Secrets to a Better Job (and More Money)

This disconnect — persistent unemployment and underemployment despite lots of vacancies — has fueled debates among economists. Some see it as proof that the workforce lacks the skills employers value, while others take it as evidence that demand for the products and services American companies make has not recovered as fully as we’d like to think. Which side of this debate you fall on will dictate your policy preferences; for example, those in the former camp generally oppose fiscal and monetary stimulus, while those in the latter support it.

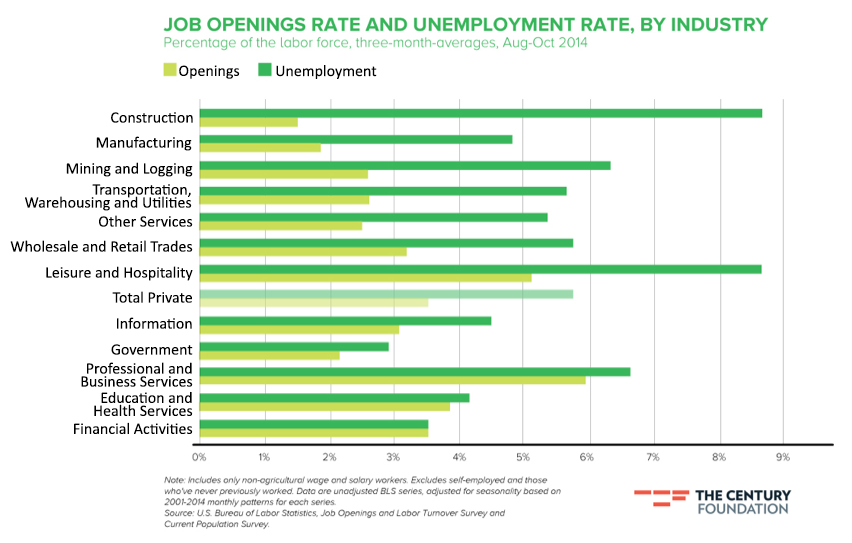

Though the debate is far from settled, we can gain insight as to where the labor market’s challenges and opportunities lie by looking at job openings and unemployment trends by industry. The next figure, also from my report, show that the goods-producing construction and manufacturing sectors are the worst places to be looking for work. In construction, an unemployment rate of 8.7 percent is paired with a job openings rate of just 1.5 percent. This means that there is only one vacancy for every six unemployed construction workers. Those seeking manufacturing jobs are only a little better off, with job seekers outnumbering vacancies at a rate of three-to-one.

By contrast, high-skill, white-collar sectors are doing quite well. In finance, there’s enough job openings for every job candidate. Workers in education and health, as well as those in professional services, have it nearly as good. (Something to keep in mind as you parse the industry statistics is that first-time job seekers, which number about 1 million in any given month, are not included, since unemployed workers are classified according to industry in which they last worked.)

Related: Taxing the Wealthy Promotes Economic Growth

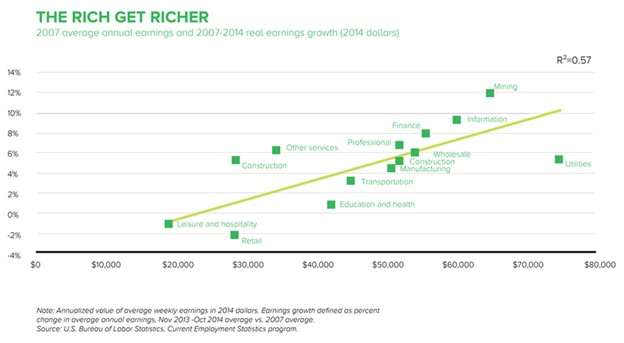

This correspondence — or lack thereof — between unemployment and openings at the industry level has real consequences for people’s well-being. Not only does the relative balance between the two dictate how easy or difficult it is to find jobs, but it also influences what those fortunate enough to find work earn. Take a look at one more figure from my report. It plots, by industry, earnings growth from 2007 to 2014 against average earnings in 2007. The trend line is upward sloping and the points are clustered pretty tightly about it, which means...the rich (or at least those people in higher-earning jobs) are getting richer.

The industries with highest average earnings are those that have seen their earnings grow the fastest. Once again, the winners are high-skill sectors, such as information and finance.

Meanwhile, blue-collar sectors have had a rough go of it. Traditional bastions of the middle class, such as manufacturing and construction, have been struggling for years, while low-paying jobs are proliferating. The two largest blue-collar sectors, leisure/hospitality and retail, which account for more than a fifth of all jobs in America, are also the lowest paying. Working year-round in these industries often means getting by on just $20,000 to $30,000 — in other words, barely breaking even with the poverty line. To make matters worse, workers in these industries actually earn less today (1 percent and 2 percent less, respectively) than they did in 2007, after adjusting for inflation. (Exceptions are mining and utilities, but these sectors together account for less than 1 percent of all jobs.)

By now, it’s a familiar refrain. America is becoming a more unequal place. But while we often talk about inequality in outcomes, like income or wealth, data on job openings make plain that inequality of opportunities is also a large part of the story. The well-educated and the technologically adept have an abundance of options, while those with less pristine pedigrees are relegated to uninspiring, unrewarding work that pays little and cares less.

Related: Americans’ 401(k) Totals Just Reached a New Record. Don’t Celebrate Yet…

We also know the fixes, though. More comprehensive training programs can reduce job search and recruitment costs. Infrastructure investments, particularly those in public transit and technology, can make good jobs more accessible. And work supports, like paid leave and child care, can enable people to better balance work and family. A minimum wage that is also a living wage wouldn’t hurt either.

If, as seems likely, the unemployment rate continues to decline in the months ahead, policymakers will increasingly debate the question of whether or not we’ve reached “full employment” — a state of labor market satiation consistent with stable inflation. When they do, they ought to consider that volume of jobs is distinct from their distribution, and that what is full is not necessarily fulfilling.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: