The Obama administration set a bold goal this week to change the way the government pays Medicare doctors. It hopes that by 2018, more than half of all payments will be tied to the quality of care doctors provide.

Currently, the majority of traditional Medicare payments are based on the traditional fee-for-service model, where doctors are paid for every surgery, physical exam and CT scan they perform, regardless of patients’ outcomes. But alternative payment methods are gaining traction in the health community based on the quality of care, doctors’ performances, patient outcomes, readmission rates and patient experience to determine how much providers should be paid.

Related: Medicare by the Numbers

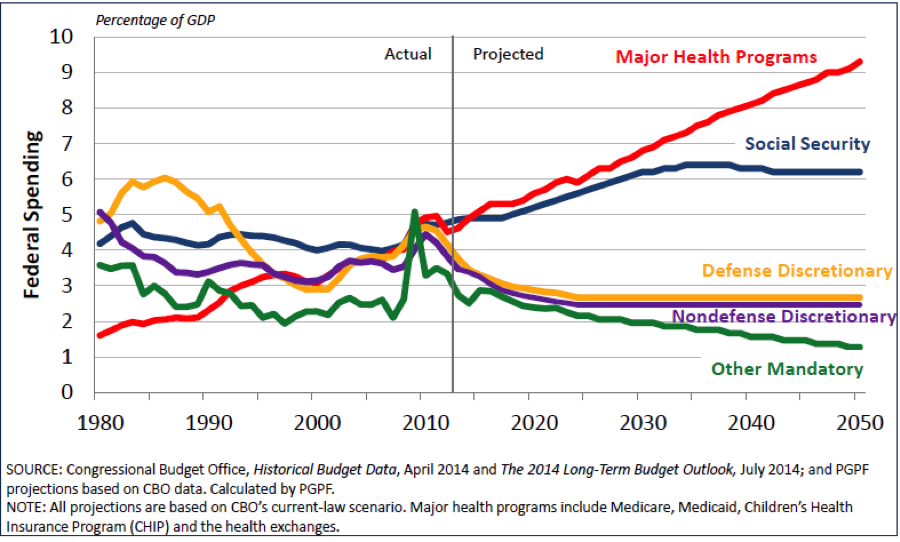

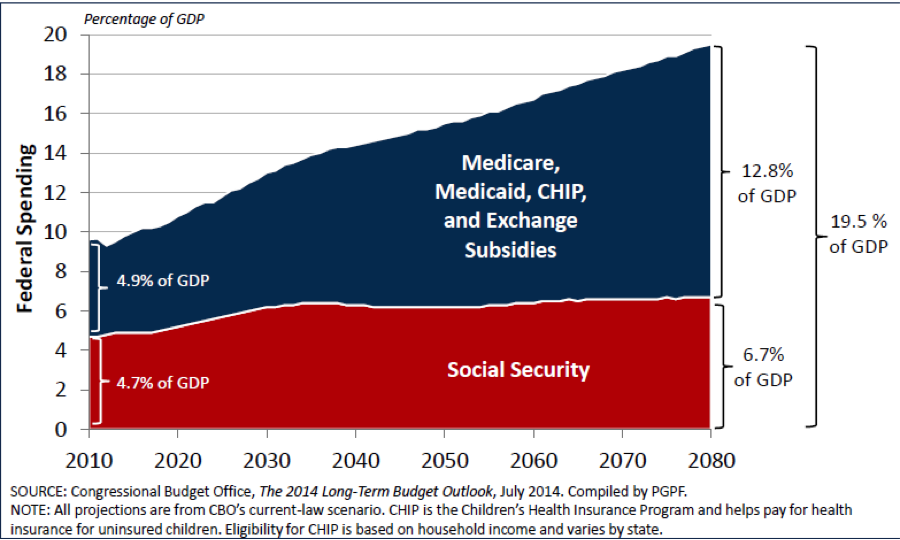

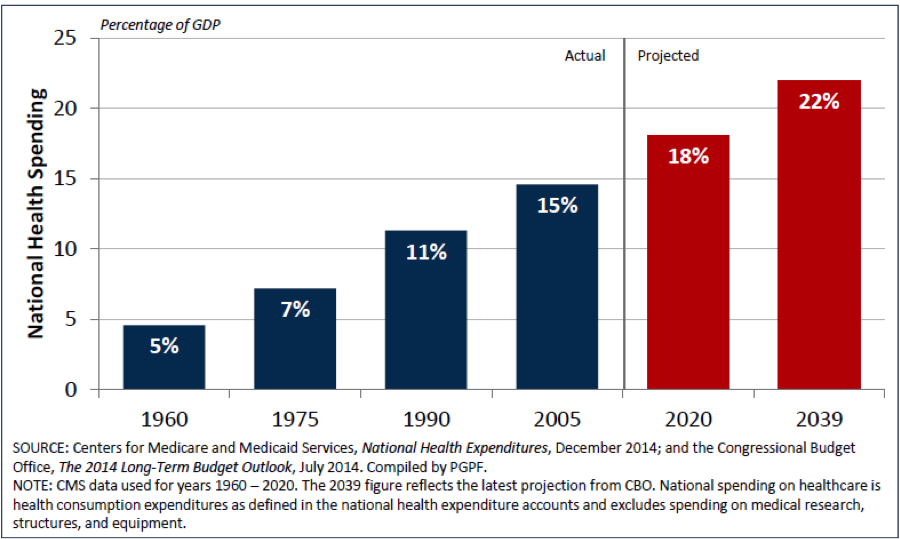

For years, lawmakers, industry leaders and health policy wonks have agreed that the U.S. health care system should eventually ditch the current fee-for-service payment model and move toward alternative payment models tied to the quality of care. They say the current model incentivizes health providers to administer more services than are sometimes necessary, which has contributed to the ballooning costs of health care. Last year, Medicare’s budget for fee-for-service payments was a whopping $362 billion.

Doctors, of course, want to know how one decides “the quality of care” short of negligence, and who will make those decisions. The greatest fear some patients have is that big city doctors – especially top surgeons and specialists – will drop out of Medicare altogether, which has already started to happen.

Steven Brill, author of America's Bitter Pill: Money, Politics, Back-Room Deals, and the Fight to Fix Our Broken Healthcare System, said, “It would certainly be more likely that doctors would agree to a regime like this if there was tort reform, if doctors wouldn’t suffer the consequences of being sued for using the kind of cost-effective procedures that the new Medicare payment reform proposes.”

Many policy makers and health providers have pushed for ways to emphasize the quality of care over the quantity.

The Affordable Care Act included several provisions that set up such alternative payment plans, including Accountable Care Organizations, Patient-Centered Medical Homes, bundled payments and other pay-for-performance programs. Currently 20 percent of traditional payments go through these programs.

Related: Major Changes to Medicare Coming for Senior Health Care

Now the administration’s plan is to expand participation in these payment models—by 2016, they expect 30 percent, then 50 percent by 2018.

So, what will that mean for the patient? In theory, better care at a lower cost, though there is limited information about how successful some of the pilot initiatives have been, including Accountable Care Organizations or ACOs.

While the shift away from fee-for-service would significantly transform the payment model, experts say the patients’ experience really won’t change all that much.

Related: Historic Medicare Data Dump Blows Lid Off Doc Pay

“There are no specific patient-care requirements that are different from regular fee-for-service Medicare. It is difficult to say if or how a move away from fee-for-service will change care for patients,” Kaiser Family Foundation’s Cristina Boccuti said.

The real change will be with how care is coordinated.

Accountable Care Organizations

Take ACOs, for example, which are just one of a handful of alternative payment programs. Under this setup, primary care physicians, hospitals and specialty doctors form networks to care for a population of patients. The entire network is then responsible for the cost and care of these patients. If it performs well on a number of metrics including patient outcomes, readmission rates, patient experience, etc., providers are rewarded with bonuses.

If a patient’s primary care physician joins an ACO, that patient now belongs to that network of doctors. The patient can seek care outside of that network, but it’s unlikely Medicare will pay for that service. The whole idea is intended to make it easier to coordinate treatment. It’s set up like a team, where the doctors can easily share patients’ information with each other and stay updated on a patient’s progress.

“The theory is that because multiple providers within a given ACO share accountability for a given patient’s care, coordination of services between the providers will improve,” Boccuti said.

Ellen Pryga, director for policy at the American Hospital Association explains why this model is more beneficial than the traditional payment model.

“Fee for service medicine has inherent inefficiencies – repeated tests, inefficiency transfer medicine – when you’re in a coordinated care setting, they’re able to avoid those things,” said Ellen Pryga, director for policy at the American Hospital Association. “When you have an integrated group of providers that are coordinating your care, you basically have a team, so it reduces some of the hassle factor of having lots of different clinicians involved.”

Still, some are concerned that ACO’s are the new version of the reviled HMO’s of the 80’s and 90’s. The healthcare teams earn bonuses by saving Medicare money—as much as 50 percent of what they save.

Two top doctors from the City University of NY School of Public Health who support Medicare reform – David U. Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler – wrote a blistering essay against Affordable Care Organizations in The Journal of General Internal Medicine in early January. In it, they accuse ACOs of being a new version of the reviled HMOs of the 70s and 80s: Their assessment was

Physicians were pressured to withhold care, and to hide that pressure from patients; bonuses of up to $150,000 annually were offered to doctors who minimized specialty referrals, inpatient care, etc. Our protest of those incentives, and a contract provision forbidding their disclosure (a 55 “gag clause”) led to “delisting.” Award-winning physicians—who often attract unprofitably sick 57 patients—were also delisted. An academic leader admonished physicians: “[We can] no longer tolerate having complex and expensive-to-treat patients encouraged to transfer to our group.” In the end, Americans concluded that fee-for-NON-service was even worse than fee-for service.

Harvard’s health economist David Cutler and others argue that HMO’s were insurers who dictated to doctors the kind of care they could provide regardless of patients’ needs. They claim that because ACO’s are providers that good care will be mandated – and that will be evident in the doctor and hospital evaluation outcomes.

The Cost Curve Keeps Rising

The abuses of overcharging for every service, every pill, every box of Kleenex for hospital patients is well documented by Brill and others who have found non-profit hospitals to be some of the most profitable “businesses” in the country.

Although most industry leaders are on board with some kind of reform, many are treading cautiously until more details are released – especially with regard to the incentives they will receive for participating, and if they will be enough to offset any potential financial risks. Another concern is how quality should be measured, as some have expressed frustration with the current way the pay-for-performance and accountable care models measure quality.

Related: Why the Medicare Cost Problem is Still Unsolved?

The administration is still hammering out the details on how it plans to encourage providers to participate in these programs. So far, there is limited evidence to suggest the programs are yielding sufficient results and savings. Of course, that’s partly because they’re new; more time will yield greater information.

“We look forward to learning more from HHS on how these new goals will be phased in,” president of the American Hospital Association, Rick Pollack, said in a statement. “At the same time, we encourage the administration to fully evaluate and improve on the delivery system reforms currently in place to ensure that we are learning from the pilot and demonstration projects to best meet patient needs.”

Pilot Programs Yield Mixed Outcomes

So far, gathering intel on how well the pilot programs are doing has been tricky, and though the information is limited, what is available isn’t all that great.

Related: If You Don’t Take Your Meds, Should Your MD Be Punished?

For example, in December, the Health and Human Services Department reported to Congress that it didn’t have results to determine if the bundled payment programs had saved Medicare money or affected the quality of care. What’s more, only 220 of the 6,690 organizations approved to participate in the program actually went forward with the new payment model.

Meanwhile, results for ACOs have been mixed. The quality measures have improved, but savings results are mixed. As Avalere Health noted, the ACOs’ results demonstrate savings to Medicare and minimal savings to individual organizations or providers.

Overall, Medicare saved $417 million through the first 220 accountable care contracts in its first year.

“Make no mistake: the results to date on the performance of APMs (alternative payment methods) do not support the administration’s enthusiasm,” John O’ Shea, visiting fellow at the Center for Health Policy Studies at the Heritage Foundation, wrote in a blog post.

“Granted, fee-for-service may have its flaws, but before blindly pushing Medicare doctors and other medical professionals out of fee-for-service and over the cliff, the Obama administration should be sure they have a safe place to land.”

Still, experts caution it’s too early to evaluate the programs. So now the big question is, will providers flock to the programs like the administration hopes? Or, will it be difficult to reach the 50 percent target by 2018?

“Providers will embrace these payment approaches more readily if they believe the approaches are fair,” Kaiser’s Boccuti said, adding that industry leaders are at the table with the administration discussing how best to meet the goal. “If the providers share at least a small part of the risks and the benefits of proving better care with lower spending, then targets can be met.”

The administration’s plan to shift away from single payer is meant to go beyond Medicare. During Monday’s announcement, HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell said the goals are meant to drive transformative change. As Peter Orszag notes in Bloomberg View, “Medicare, the gorilla of health care, is the place to send that message; it's large enough to set norms throughout the sector.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: