Something odd is happening in the government bond market: Interest rates are pricing in a debt-deflation cataclysm.

How else can you explain the fact that the yield on the U.S. 30-year bond hit a record low of 2.4 percent on Wednesday? Or that Japanese and German 10-year yields are plumbing record lows? Or that five-year yields of bonds issued by Eurozone safe havens Finland, Germany and Switzerland are in outright negative territory?

Something is very wrong here.

Related: Swiss Franc Soars After SNB Abandons Cap on Currency

For the U.S. 30-year yield, current levels have dropped below the lows set during the 2008 financial panic and 2012 pre-QE3 slowdown. And this is down from the post-recession high of 4.85 percent set in 2010 and a recent high of nearly 4 percent set in late 2013.

With stocks not far from late December's record highs, with job growth surging, investor confidence at extremes, consumer and small business confidence high, GDP growth strong and the Federal Reserve telling everyone it's preparing for its first interest rate hike since 2006, the bond market's message comes off as downright weird.

This is especially true considering the consensus was for interest rates to drift higher this year, something that everyone from the cover of Barron's to the cavalcade of Wall Street analysts have been echoing.

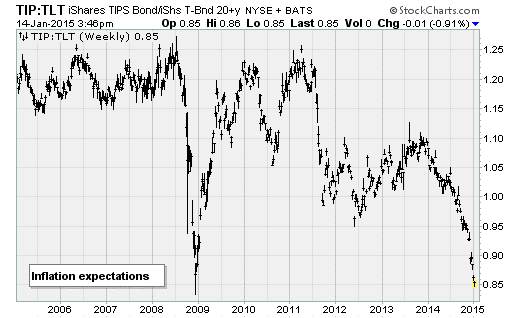

But the bond market’s fear is corroborated by the epic breakdown in industrial commodities, with crude oil down nearly 60 percent from its summertime highs as copper smashes down to mid-2009 levels. It's corroborated by a drop in market-derived inflation expectations, which by my rough measure shown above of the iShares Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities Bond Fund (TIP) vs. the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond Fund (TLT), has returned to the panic lows following the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

And it's also now being corroborated by weakness in specifically affected areas of the stock market, such as energy and materials stocks, as well as the companies that service those industries, such as heavy equipment maker Caterpillar (NYSE:CAT). The iShares Energy SPDR (XLE) has lost more than a quarter of its value since June, returning to a trading range it was at in 2011. CAT is down more than 22 percent.

Related: Why Oil Prices Are Headed Below $35 a Barrel

Stock market volatility is drifting higher, and nervousness is rising as people start connecting the dots. There has been a clear increase in share price whipsaws over the last few months. The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) — known as Wall Street's "fear gauge" — is in the midst of its most persistent period of strength since the chaos surrounding the 2011 downgrade of the U.S. credit rating.

For all the influence of the global central banks in this business cycle, with the Federal Reserve alone taking its monetary base from $800 billion to north of $4 trillion while holding short-term interest rates near zero percent since 2008, the bond market still operates according to the concepts of basic macroeconomics.

And it's warning that we're in trouble. The problem is threefold:

- The evidence is building that the global economy is slowing, led by weakness in Asia and Europe. The JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI, which measures factory activity, last month dropped to its lowest level since August 2013. Activity is declining outright on a month-over-month basis in China, Greece, Austria, Italy and France.

- This comes as the developed world governments, reacting to the blowup of private sector debts (mostly real estate), recession and the risk to the financial system in 2008-2009, have piled on public debt. China is in the mix here too, with local government and private credit exploding higher, fueling fixed-asset investment bubbles, overcapacity and now an unresolved bad debt problem that we got a quick taste of in early 2014. In Italy, the government debt-to-GDP ratio has grown from 104 percent in 2008 to 133 percent, with no signs of slowing.

- All this is occurring at a time of low global inflation, tipping into outright deflation in some areas. Prices at Chinese factory gates have been dropping for months. The Eurozone is expected to have fallen into outright deflation in December. Capital Economics expects consumer price deflation in the United States for January.

Boiling it all down, these market moves are due to Chinese factory overcapacity, Japanese exchange rate mercantilism and Eurozone fiscal austerity. They’ve been accelerated by the collapse in energy prices, which looks set to continue.

The combination of all three trends forms a potent economic poison that has ensnared Japan for decades: A debt-deflation depression.

Related: Can the U.S. Boom While the World Busts?

It's a self-reinforcing cycle whereby economic weakness pushes up budget deficits (as tax revenues drop and spending on things like food stamps rise) and creates deflation amid a lack of demand and an excess of supply. The combination causes public debts to balloon. Efforts to raise taxes and cut spending to contain rising debt levels only tighten the trap.

The debt-deflation spiral raises the real, inflation-adjusted cost of debt as household and businesses try to pay off fixed obligations amid falling wages and revenues. Asset values are pulled lower. And the crisis deepens.

The problem isn't new.

The theory behind the dynamic was developed by economist Irving Fisher in his Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions in 1933, based on data from the Great Depression as well as the depressions of 1837-1841 and 1873-1879. If you're interested, it's worth a read and can be found hosted by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank here.

The only way out is to engineer higher inflation and/or wipe the debts away via default. If the problem deepens, as the bond market is warning, I expect more drastic solutions — more so than the stimulus efforts of 2008-2009 and the "quantitative easing" we've seen in recent years — to be discussed.

Greece will probably be the test case following its upcoming election, with the anti-bailout Syriza party leading the polls and demanding Europe grant it debt forgiveness on par with what Germany enjoyed in the 1950s.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: