Indiana began a big crackdown on identity crooks this year and the results are startling: The state has saved Hoosier taxpayers $85 million so far by not paying out bogus tax refunds. The savings come from using research firm LexisNexis’ giant database to verify the identities on state income tax returns. By spotting false or stolen identities, the state can determine which returns are concocted and block the fake refunds.

The Indiana Department of Revenue’s identity-matching effort is indicative of the types of data-driven programs most states have undertaken to combat an exploding number of sham tax refund filings, false Medicaid and unemployment claims and public assistance fraud that can cost taxpayers billions of dollars.

Related: How Big Data Can Stop Traffic Jams and More

Indiana’s results are proof that using data has a payoff. And they provide a tantalizing glimpse of the cost-savings states could get from applying a government-wide “big data” approach to combatting the fraudulent claims states face in an Internet age when identity theft is rampant. Indiana spotted 74,782 returns filed with stolen or manufactured identities as of the end of last month with its new identity-matching effort. Without it, the Department of Revenue caught just 1,500 cases of identity theft out of more than 3 million returns filed in all of 2013.

Other Indiana agencies are mining data, matching data sets and performing some data analysis to detect fraud, said Matthew Donahue, the Revenue Department’s leader of strategic transformation initiatives. But, he said, there’s no state government-wide data sharing, combination of databases or use of data analysis across them to attack fraud in a big data way. That’s true in nearly all the states, said Doug Robinson, executive director of the National Association of State Chief Information Officers.

Despite the vast databases of personal, business and other information that states possess, Robinson said, only a few states are starting to leverage them in a strategic, big data way to detect and prevent fraud—or to apply them to other pressing management, economic or social problems states face.

Related: Big Data Poses Big Challenges for the Pentagon

Instead, he said, states largely house their databases separately in tax, health, revenue, welfare, motor vehicles, voter registration and professional licensing departments and offices. Other agencies cannot easily access the data, which is often not in the same format. Thus, it cannot be quickly managed, matched, mined or otherwise analyzed in an enterprising fashion to catch and prevent fraud or attack other problems.

“States are data engines at their core,” Robinson said. But, he said, “just because states have a lot of data doesn’t mean they’ve met the definition of big data. … Very few states have taken an enterprise approach to it.”

States Hit With ‘Widespread Fraud’

If famed bank robber Willie Sutton were alive today, he might well be an identity thief—after all, that’s where the money is. And instead of looking to banks, he’d look to states.

“If government is giving out a benefit or a payment … then they are being defrauded in enormous ways,” said Andy Bucholz, vice president of market planning for LexisNexis Risk Solutions, which Indiana contracted with to verify identities on tax returns. “This is widespread. Nobody knows the true costs yet. A lot of government agencies don’t want to raise their hands and say we’ve been defrauded.” (See an interactive map on the percentage of complaints of identity theft involving public documents and benefits reported in your state last year.)

Related: Museums See Big Data As Profitable New Art Form

The cost to states likely has run into the billions of dollars in recent years as states have moved services online and as identity theft has exploded nationally, Bucholz said. It’s hard to tell in online filings if people really are who they say they are.

Identity thieves lift personal information, such as dates of birth, Social Security numbers, addresses and bank account numbers, everywhere from doctor’s offices to Internet hacking, and use it to try to bilk state programs by making bogus claims, Bucholz said.

Like Indiana, many states increasingly have taken action against the scams and other improper payments by using identity verification and other data tools, especially in claims for unemployment insurance benefits:

- By matching unemployment claims against the identities of people jailed in country prisons, Pennsylvania discovered and stopped almost 19,000 payments made in 2013 to inmates who can’t lawfully collect the benefits. The state estimates the program will save taxpayers about $100 million a year.

- New Mexico cut unemployment insurance fraud by about $10 million, or 60 percent, last year after integrating its unemployment tax and claims systems. The new system lets the state quickly match documentation between employers and claimants to reduce fraud, and to detect and recover improper payments.

- New Jersey has blocked nearly $450 million in improper unemployment payments the last four years, as Stateline has reported, by identifying 300,000 people who tried to wrongfully collect benefits through identity theft or other schemes or mistakes.

Florida has taken an aggressive approach to rooting out fraudulent or improper claims for food stamps, cash assistance for needy families and Medicaid by verifying claimants are who they say they are with the LexisNexis identity database before issuing payments.

Related: You May Be One of Millions Whose ID Was Stolen and Sold

The state kept $32.8 million in inappropriate payments “from going out the door” in its last fiscal year that ended June 30, said Andrew McClenahan, director of public benefits integrity for Florida’s Department of Children and Families. It also detected $34.4 million in overpayments and recovered more than $19.4 million of that money.

“I don’t want it to appear as if we’re waging a war on the poor and unfortunate,” McClenahan said of attacking public assistance fraud. But, he said, it’s “one of the things we have to do as stewards of taxpayers’ money.”

New York’s Department of Taxation and Finance has expanded its program to prevent and track down tax cheats in recent years. It now uses data screening and analytics to review the 10 million personal income tax returns it receives each year. Last year, it spotted more than 255,000 inappropriate refunds and kept $413 million from being paid. Some states are taking the experience they’ve gained in one agency and applying it to others. After launching a program to recover improper unemployment insurance payments, Michigan began using data analytics software to look for anomalies or patterns that suggest fraud in other areas, such as its Food Assistance Program.

Few States Employ ‘Big Data’

To integrate its data and leverage the information across all of state government, North Carolina has consolidated its data analytics efforts, including its data-based fraud detection program, under its Office of Information Technology Services. The goal is to apply big data-style analytics across all agencies to improve business decisions.

Related: How You're Shaping the Future Through Big Data

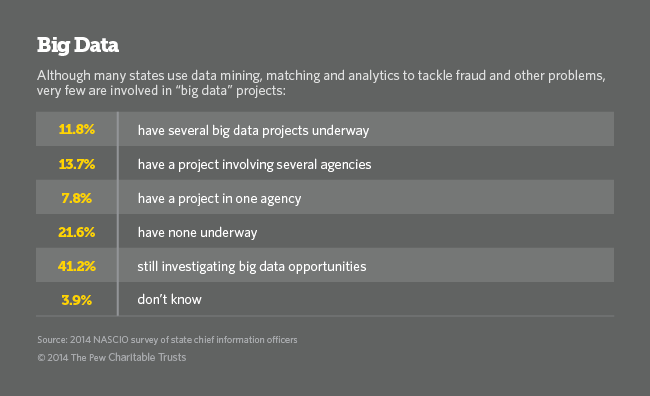

Few states, according to a survey of the states’ chief information officers released in September, have big data projects underway. Only 13.7 percent have a big data project that involves several agencies. One in five states has no big data project going at all.

Indiana is an exception, but its big data project isn’t focused on fraud. Instead, it aims to assess why Indiana has a high infant mortality rate compared to the national average. Data from various agencies—health, criminal justice, social services and the environment—will be analyzed for causes of the high mortality so the state can respond with the right policies and programs. It’s the first project undertaken by Indiana’s new Management and Performance Hub, created by Republican Gov. Mike Pence to share data, take on the state’s toughest challenges and produce better results.

In trying to take a big data approach to problems, states face hurdles beyond getting disparate data out of agency silos and making it compatible. Some data, such as voter registrations, reside in separate state constitutional offices, which poses a jurisdictional problem. And there are privacy concerns.

Most states use third-party software or services offered by a host of private companies to analyze and apply their data to a task, just as Indiana’s Department of Revenue uses LexisNexis to authenticate identities. Indiana doesn’t send LexisNexis tax returns. Instead, it sends portions of information from returns that LexisNexis compares to its identity database, which is pulled from public and commercial records and is one of the largest in the world. The state also sends questions to taxpayers that only the real tax filer can answer.

Related: States Turn to Cloud Computing for Cost Savings

Indiana’s Donahue said its identity verification program is just a first step in combating tax fraud. The Department is developing predictive analytics to try to spot patterns or anomalies in returns to try to stay ahead of the crooks, who still are filing bogus refunds six months after the flurry of tax season. “We have to be flexible,” he said. “The crooks are adapting and changing.” What Donahue won’t be able to bring to bear on the crooks, at least not yet, are data sets from across all Indiana agencies. But maybe down the line, now that the state’s new Management and Performance Hub is knocking down data silos, he will.

This article originally appeared in Stateline, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.