“I didn’t find him,” my younger brother told me over the phone.

“Are you sure? Did you go over all the bodies in the morgue?” I asked.

“Yes. I went through hundreds of bodies.”

“I will come and check them myself. Wait for me.”

I arrived at Baghdad central morgue at midday. The guards asked me to identify the neighborhood where my father had been kidnapped. At that time--December 19, 2006--the Ministry of Health was controlled by the Mahdi army, the Shiite militia that was involved in the sectarian war. The guards at the morgue gate were militiamen and asked leading questions to determine if I was Sunni or Shiite. As a Shiite, I avoided the fate of those who were not.

At the morgue, the scene was beyond description. There were bodies everywhere--three large halls were full of corpses. The dead lined the halls and walkways outside. I couldn’t smell anything that day because I had the flu, but my brother had to cover his nose to avoid the smell of deteriorating flesh. Because there were so many, putting the bodies in refrigerators was impossible. Instead, they lay on the ground one next to the other.

Two of the large halls had “fresh” bodies, which had been delivered in the last two days. I estimated that each hall had about a hundred bodies. I went through every one of them, examining the faces carefully. My younger brother had done that twice. I glanced at the third hall where older bodies had been dumped, but didn’t go in. I walked through the smaller rooms and the walkways, searching the colorless faces of the dead. Screens showed bodies that had been buried after the criminal autopsy had been completed. My father was not there.

I was then thirty-one years old and working as a press officer at the Iraqi Ministry of Justice where my sister also worked as a translator. I am the oldest among two brothers and a sister. My brother was a software programmer at the Ministry of Electricity. My youngest brother was in his final year of high school. My mother was a retired social worker. All of us had lived through many years of war.

Related: The Tide Is Turning Against ISIS in Iraq

The morgue was like a terrifying horror movie. The bodies there showed marks of electric drills, burning, bullets, beating with everything you can imagine, torture by whipping on almost every part of the body including the face. I couldn’t count how many faces I saw whose eye or nose or mouth were destroyed and unrecognizable.

The drilling – which was the signature of the Mahdi army – was particularly awful. They focused on the wrists and the feet. But there were many bodies that had holes drilled in so many other places, like the head, the neck or even eyes or noses and other parts. Many bodies had the hands tied up. Almost all bodies were male, including teenagers and elderly men.

My father, 65 year-old Mohammed Hussein Ra’uf had been kidnapped from our home in Amiriya, western Baghdad the day before by ISIS militants who controlled that Sunni neighborhood. At that time, they called themselves the Islamic State of Iraq. Iraq -- including Baghdad -- was embroiled in a violent sectarian war. Minorities in dominant majority areas, like my father, had to abandon their houses or face death. But it was not easy to leave if you were not rich. Those without other resources were the unluckiest of the unlucky. We were among them.

Related: How ISIS Wages a Brutal and Hideous War on Women

My father was middle-class and well-connected, but retired. He was a former public servant and a politician. As a law graduate, he was one of the founders of the Iraqi Ministry of Labor and he co-drafted the first Iraqi social security law in the 1970s. He was also a politician who believed in Arab unity.

On August 2006, our house was fired upon from a near distance by militants in a car while my brother was arriving from work. He survived and nobody was harmed. But the message was clear: Leave now or face death. We were among the last Shiite families in Amiriya. We had lived in that house, which my father built, for 25 years.

Very soon after, we left and rented another house in a neighborhood in eastern Baghdad. On the day of his kidnapping and death, my father went to our old house and saw ISIS militants inside. He confronted them and told them to leave. They said they wanted to talk to him at a nearby mosque. So he took his car and followed them. We never saw him alive again.

Related: ISIS Delivers “Shock and Awe” with Arms from U.S., China and Russia

After my father was kidnapped, I called every Sunni person we knew for help. We were secular Shiites. Most of our friends were Sunni. But on that day, many abandoned us. I called my younger brother’s best friend, who lived in Amiriya. This friend spent a decade visiting us almost every day. He hung up on me. I called my own best Sunni friend, just to be asked by him whether we are “the family of the Iranian old woman” or not. That woman was my late grandmother. She was not Iranian at all. Her mother was Iranian, though.

For the Sunni minority that ruled Iraq for 14 centuries with an iron fist, Iran is the enemy that they wish they could obliterate. Saddam Hussein launched an 8-year-long war against Iran and he used chemical weapons against them. Under Saddam, the Iraqi Shiite population suffered. Iran was the only Shiite country then.

After leaving the Baghdad central morgue, I visited another morgue on the western side of Baghdad. The refrigerating system there had broken down and the halls were so full that the bodies occupied all of the empty space on the floors, spilling out of the building. This time, I was accompanied by my older cousins. We started in the walkways since the corpses there were the most recent. Suddenly, my cousin said, “That is him.”

I went to the body and saw the man who worked so hard his entire life to make sure that I was fed, clothed, protected, educated and employed. I saw my father’s dead body.

Related: 9 ISIS Weapons That Will Shock You

My father was really a handsome man. When he was young and had a mustache, he sometimes looked like the late British actor Laurence Olivier. When he got older and removed the mustache and wore glasses, he sometimes looked like the late U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was tall and pale, with a photogenic face. People always thought he was a decade younger than he was.

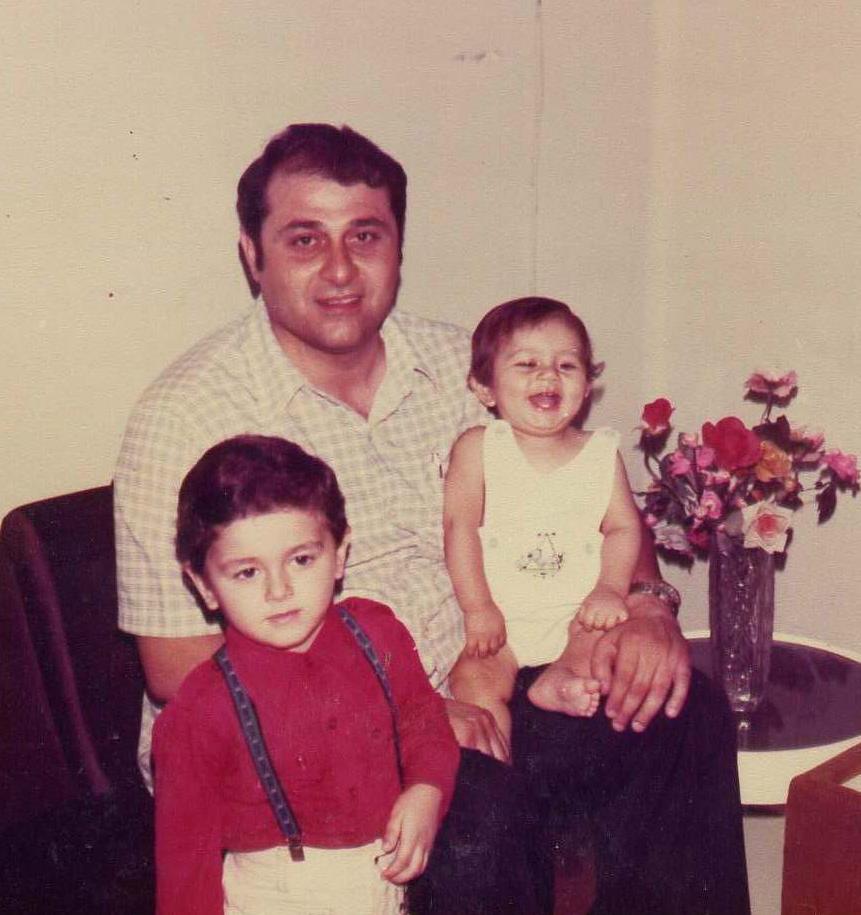

Mohammed Hussein Ra’uf with the author and his brother.

Lying on the ground wearing his dark pants, his yellow shirt, dark brown sweater and jacket, his face looked unchanged except for his red eyes and opened mouth. But when I sat next to him, I saw a relatively large hole in the right side of his neck. Both wrists had deep drill wounds. I saw another hole made by a bullet in the heart area. He bled when we moved him.

I later figured out that my father wasn’t tortured. He was made to sit on his knees, in ISIS’s execution position. His hands were not tied. He thought that he could minimize the injuries of the bullet if he could put his hands in their way. The big hole in his neck was from a certain kind of bullet that makes large wounds when entering human flesh.

Despite my father being half blind and half deaf; despite that he couldn’t smell at all due to a car accident he had while serving in the government, which forced him to retire for being unfit to serve; and despite that he was 65 and unarmed, ISIS members killed him from close range. Their only reason was that he was technically Shiite.

For ISIS, Shiites are not only not Muslims. They are Muslims who converted from the faith and they must be killed. But ISIS is a true Iraqi product. It used its extreme twisted interpretation of Islam for something not religious at all. Sunnis ruled Iraq until 2003. They have never accepted the fact that in a democracy the majority will rule.

The most extreme Sunni Iraqis will never accept a real democracy and they will kill as many Shiites as they can, or they will destroy the entire country if Shiites don’t return power to the Sunnis.

My father lived all his life as a secular man. Most of his friends were Sunnis. His political party believed in Arab unity with other Sunni Arabs in the Arab world. He spent the last few years of his life defending Sunni detainees arrested by the U.S. military and calling for a non-sectarian Iraq. But that was not enough to spare his life by ISIS. He was just another Shiite that needed to be eliminated.

I never saw my house again.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: