WASHINGTON (Reuters) - President Barack Obama's administration, seeking to revive stalled Afghan peace talks, may alter plans to transfer Taliban detainees from Guantanamo Bay prison after its initial proposal fell foul of political opponents at home and the insurgents themselves.

As foreign forces prepare to exit Afghanistan, the White House had hoped to lay the groundwork for peace talks by sending five Taliban prisoners, some seen as among the most threatening detainees at Guantanamo, to Qatar to rejoin other Taliban members opening a political office there.

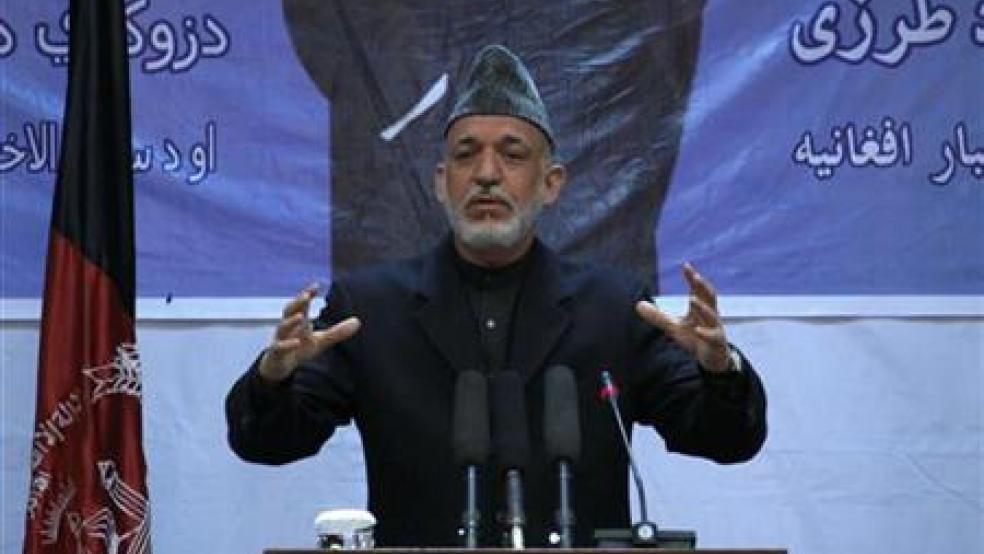

In return, the Taliban would make its own good-faith gestures, denouncing terrorism and supporting the hoped-for talks with the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

While that plan has not been scotched entirely, several sources familiar with preliminary discussions within the U.S. government said the United States may instead, as an initial gesture meant to revive diplomacy, send one of those detainees directly to Afghan government custody.

The sources identified the detainee as a former Taliban regional governor named Khairullah Khairkhwa, who is seen by American officials as less dangerous than other senior Taliban detainees now held at the U.S. military prison in Cuba.

No final decision appears to have been made on Khairkhwa's fate.

A senior Obama administration official, while not disputing that Khairkhwa's unilateral transfer had been suggested, cautioned that it was still at a "brainstorming" level. The onus was still on the Taliban to show it is interested in Afghan reconciliation, he said.

"It's most definitely not policy," said the senior official, speaking on condition of anonymity. "At the moment we've made clear what we expect from reconciliation ... and the Taliban understand that, full stop."

More than a year ago, the White House launched what began as a secretive diplomatic bid to coax the Taliban, the Islamist group that ruled Afghanistan until 2001, into peace talks. That campaign has become central to U.S. strategy as officials conclude the Afghan war will not end on the battlefield alone.

It remains far from clear whether the Taliban would embrace sharing power in Afghanistan and whether the militants are cohesive enough to agree on a joint diplomatic approach.

But Washington's strategy, before a May summit of NATO leaders in Chicago, is to build on what officials see as military progress against the Taliban, and encouraging signs from the Afghan and Pakistani governments, to heap pressure on the Islamist group.

"As we head into Chicago obviously we'll continue to highlight each of those (areas) and we'll continue to work with Congress," the U.S. official said.

The Chicago summit is expected to further detail plans for the withdrawal of most of NATO's 130,000 troops there by the end of 2014 and set the course for future ties between Afghanistan and the West.

A LONG SHOT, BUT FEW ALTERNATIVES

U.S. efforts to broker the talks were dealt a blow last month when the Taliban suspended its participation and appeared to reject even minimal restrictions for prisoners transferred to Qatar.

From the beginning, a transfer of Taliban prisoners has posed major political risks for Obama in an election year.

U.S. lawmakers from both parties, but particularly Republicans, have warned that prisoners such as Mullah Mohammed Fazl, a "high-risk" detainee and former Taliban military commander alleged to be responsible for the killing of thousands of minority Shi'ite Muslims, might rejoin militant operations.

The transfer proposal has also been divisive within the Obama administration. Because Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, under U.S. law, must personally approve the transfer, Pentagon officials worry their agency will be deemed responsible for any future actions by those detainees.

Partly for those reasons, U.S. negotiators are now focusing on Khairkhwa. Once the Taliban's governor of western Herat province, he was also a Taliban spokesman and interior minister.

The senior U.S. official said Karzai has been asking the United States for years to send Khairkhwa, imprisoned since 2002 at Guantanamo Bay, back to Afghanistan. The Taliban has long demanded release of its prisoners, in part as a good-faith move.

U.S. military assessments that have been made public characterize Khairkhwa as a 'high-risk' detainee and a 'direct' associate of the late al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and Taliban leader Mullah Omar.

But they also describe him as more of a civilian than a military figure, and he is said to be a friend of Karzai.

Khairkhwa was captured in Pakistan in early 2002, allegedly while seeking to negotiate surrender and integration into the new Afghan government.

"If you were to take all the senior leaders associated with the Taliban since the start of the movement, and try to find the inclusive figures, acceptable to fellow Afghans and competent to work for a political agreement, Khairkhwa would definitely be in the top five," said Michael Semple, a former U.N. official with more than 20 years experience in Afghanistan.

SETBACKS

Afghanistan's High Peace Council, under the leadership of the late former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, had advocated for Khairkhwa's release, saying he might play a positive role in the peace process.

"The cause of Mullah Khairullah Khairkhwa is good for peace, and totally acceptable to Karzai," Semple said, in part because Karzai and Khairkhwa both come from the Popalzai tribe.

Last year, a U.S. federal court rejected a challenge to Khairkhwa's detention by his lawyers, and an appeal is now pending.

If a unilateral transfer were approved, Khairkhwa would be moved to Afghan custody in a country other than Qatar, without involvement of the Taliban. It was not immediately clear whether this might mean a transfer directly back to Afghanistan.

The transfer would still require the Obama administration to notify Congress 30 days ahead of time. But the hope is that Khairkhwa's transfer would avoid the furor in Congress that moving the other prisoners might bring.

Efforts to salvage the peace process follow a series of U.S. setbacks in Afghanistan: bloody riots caused by soldiers' burning of the Koran; a staff sergeant's alleged massacre of 17 villagers; and an 18-hour militant assault of Kabul last week.

Still, officials point to statistics charting a drop in 'enemy-initiated attacks' this spring. They were encouraged by recent steps to finalize a deal outlining the U.S.-Afghan relationship, along with statements of support for the peace process by Pakistani Prime Minister Yusuf Raza Gilani.

U.S. officials hope to use all these developments to coax the Taliban's leadership, under pressure from less senior fighters who oppose negotiations, to formally resume talks.

(Additional reporting by Hamid Shalizi and Rob Taylor in KABUL; Editing by Warren Strobel and David Storey)