The October jobs report released Friday was met with a lukewarm response. Payroll gains totaled 214,000 jobs, down from the 240,000 average of the last five months. The average workweek was slightly longer. Wage pressure remains tepid, running at a 2 percent annual rate.

But the big news was that the unemployment rate dropped to 5.8 percent — returning to a level not seen since July 2008. Much this decline has been driven by folks dropping out of the workforce, pushing the employment-to-population ratio to levels not seen since the early 1980s (although it's been improving slightly lately).

Finally, more than five years after the recession officially ended in June 2009, the job market is beginning to normalize. That means that the last piece of the economic recovery, higher wages, should arrive shortly. In other words, it'll soon be time to start asking for raises again.

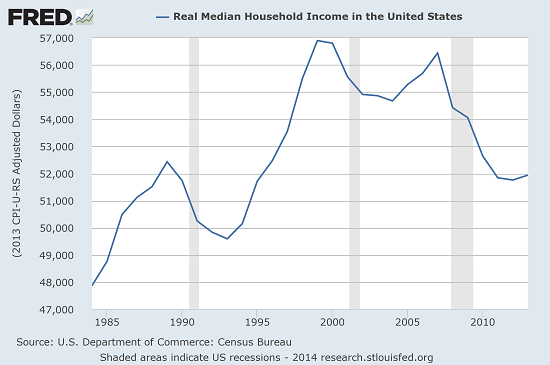

This is a huge deal since the bulk of our economic problems are connected to the fact that inflation-adjusted median household income in the U.S. is down about 10 percent from the peak reached in the late 1990s, as shown in the chart above. Much flows from this fact: Overreliance on debt, the impetus behind all the housing bubble craziness, and the growing problem of income inequality over the last few years.

The good news is that the economy seems to be catching a great tailwind. U.S. GDP growth has averaged an annualized growth rate of more than 4 percent in four of the last five quarters (with 1Q14 being the outlier due in part to the polar vortex and severe winter weather). The accelerating retirement of Baby Boomers, and the tightening conditions in the job market, has resulted in the best pace of job creation since the 1990s.

Related: Election Day’s Minimum Wage Hikes Could Inspire More States

As a result, economists at Deutsche Bank believe the unemployment rate could drop below the 5 percent threshold by the end of 2015. If so, that would exceed the Federal Reserve's 5.5 percent median estimate — and surprise a lot of people. The economists believe that "there is mounting evidence that excess labor market slack is diminishing rapidly."

This is borne out in private surveys of small businesses, where hiring managers note they are having a tougher and tougher time finding qualified workers. Moreover, they are preparing to pay more for the workers they are finding. The government's job openings data bears out the trend too, as it has improved to the best level since 2001.

The job market is hitting the sweet spot. From early 2011 to the start of 2014, the unemployment rate was dropping an average rate of around 0.8 percent every 12 months. In the first half of this year, the rate of decline accelerated to about 1.2 percent. Now, it's over 1.3 percent.

The Fed didn't expect things to improve this fast. In December 2012, the Fed's 2013 year-end forecast was for a 7.5 percent unemployment rate (it ended at 6.7 percent). At the end of 2013, the central bank’s officials were looking for 6.5 percent a year out. We are already at 5.8 percent. The bond market is even further behind.

Related: Is the Fed Wrong Again on Interest Rate Hikes and Inflation?

The longer this continues, and by all indications it's going to continue, Deutsche Bank believes the odds of an acceleration in wage inflation "rises significantly." As the unemployment rate keeps falling, and the pool of workers available for hire shrinks, we should see compensation start to rise. That'll be great news for households and the long-term health of the economy. But it'll bad news for corporate profit margins and the Fed's ability to hold interest rates down.

So how long before the magic starts happening?

In May, New York Federal Reserve president William Dudley said that he didn't believe inflation would become a problem worthy of a policy response until wage gains accelerated from a 2 percent annual rate to something closer to 3.5 percent. His sentiment has been echoed by other Fed officials. The 2 percent rate has been in play since 2009, resulting in the weakest period of wage gains on record.

Excluding the high-inflation period of the 1970s, history tells us that wages start to turn higher when the unemployment rate hits 5.9 percent, on average, on the way down. The range of values triggering the turnaround in wages is relatively wide, from 7.5 percent in 1984 to 5.2 percent in 1964. Yet it's clear we're finally getting close to something happening.

Related: Are Economists Ready for Income Redistribution?

During the last two business cycles, wages turned when the unemployment rate hit 6.1 percent and 5.8 percent.

There are many variables in play. Policymakers are still trying to figure out how much structural damage has been done to the labor market. If many of the unemployed have lost skills, are close to retirement, or are simply no longer employable, wage gains could increase faster than expected. This is reflected in what's known as the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment or NAIRU, which Deutsche Bank believes is around 6 percent but the Fed believes is around 5.5 percent to 5.7 percent.

If, on the other hand, folks are ready and willing to come back into the labor force, we could need to see the unemployment rate drop to 5.2 percent — as it did in 1996 — before we hit Dudley's 3.5 percent wage-gain threshold.

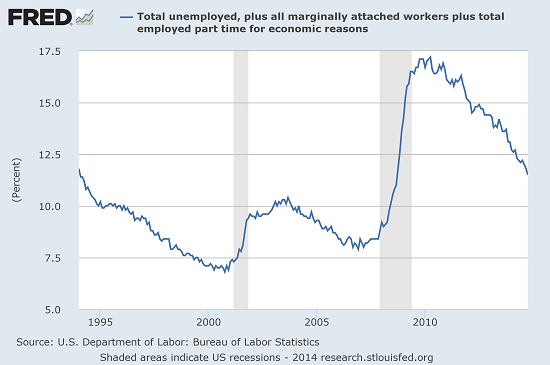

As a result, a better indicator of where we're at could come from the U-6 measure of unemployment, which takes the regular unemployment rate and adds discouraged workers as well as part-time workers who want full-time employment. At 11.5 percent, this measure is higher than suggested by the narrow 5.8 percent unemployment rate, confirming that more people are marginally attached to the labor force than usual.

During the last two business cycles, wages didn't really take off until the U-6 measure fell to 10 percent. As things stand now, that could require the narrow unemployment rate to fall to 4.9 percent according to Deutsche Bank estimates — something that could happen, at the current pace, by next summer.

So get ready: By the time the fireworks fill the sky during the next Independence Day holiday, you should be hitting up the boss for a bigger paycheck.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: