Hundreds of Americans have flown to Liberia in the past few days. Thousands more are on the way.

This Ebola corps is a collection of doctors, nurses, scientists, soldiers, aviators, technicians, mechanics and engineers. Many are volunteers with nonprofit organizations or the government, including uniformed doctors and nurses from the little-known U.S. Public Health Service. Most are military personnel, snapping a salute when are assigned to their mission — “Operation United Assistance.” It does not qualify for combat pay, only hardship-duty incentive pay, which is about $5 a day — before taxes.

Related: Ebola-Quarantined Nurse Takes Issue with Her Treatment

“We’re going over there to take the fight to the enemy,” said Sgt. Maj. John Kolodgy of the 2nd battalion of the 501st Aviation Regiment, stationed in Fort Bliss, which is sending 85 soldiers this weekend to Liberia to provide airlift capability. “In this situation the enemy is Ebola and the spread of Ebola in Africa.”

The “Iron Knights” from Fort Bliss, in El Paso, will join hundreds of soldiers from the 101st Airborne who departed for Liberia in flights from Kentucky’s Fort Campbell on Thursday and Saturday. The U.S. military presence in West Africa is expected to grow to more than 900 troops by Sunday, a number that will climb to 3,900 in coming weeks.

Global health officials have a plan to bring Ebola victims out of their homes, where they can easily spread the virus, and treat them in health facilities. The 101st Airborne officially took command Saturday of the effort to build 17 Ebola treatment units (ETUs) in Liberia with 100 beds each.

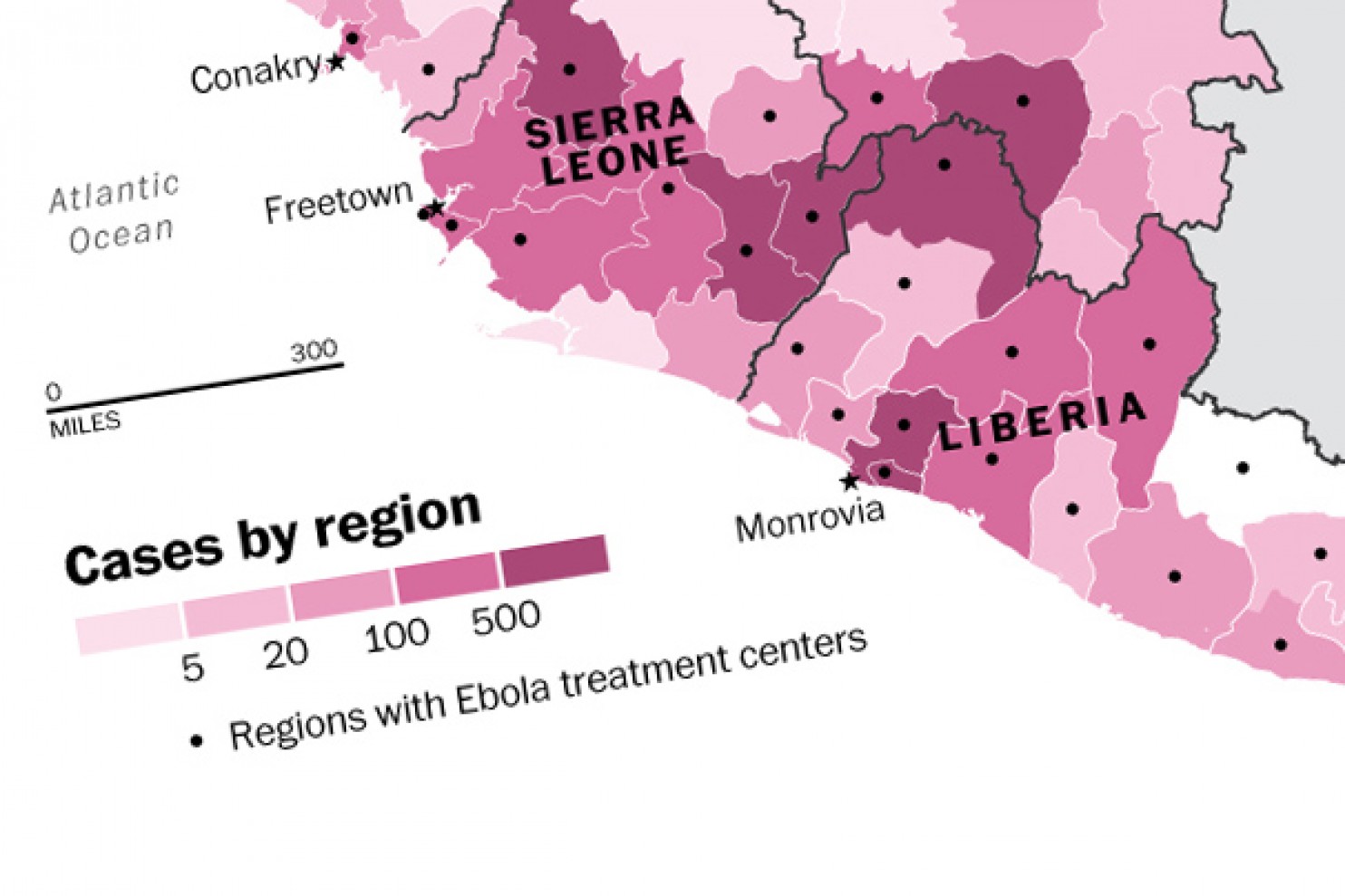

The largest Ebola outbreak on record continues to spread through West Africa.

Related: 9 Ways Robots Could Help Battle Ebola

For the military, this is an unusual mission. Past humanitarian efforts have involved events that have already occurred, such as hurricanes, typhoons and earthquakes, but this crisis is still developing, generated by a pathogen that is dynamic and unpredictable.

The U.S. military is deploying primarily to Liberia, though the U.S. civilian operations include Guinea, Sierra Leone and other nations in West Africa. President Obama announced Sept. 16 that the military would provide support to the civilian-run effort that had failed to keep the epidemic from growing exponentially. The question now is whether this more muscular response is too little too late.

The outbreak on Saturday officially topped 10,000 cases — 10,141 confirmed or suspected cases and 4,922 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Those are only the official numbers; the affected region includes rural areas and forested regions where disease surveillance has been minimal. The virus has now spread to Mali, where an infected 2-year-old girl who traveled from Guinea with her grandmother died Friday. (A small, unrelated outbreak of Ebola is underway in Congo, which has more experience fighting the disease.)

The WHO said this past week that there is no evidence the infection rate is dropping.

Related: How to Protect Yourself from Ebola

A report in the Lancet medical journal said, based on a mathematical model of the outbreak in Liberia, that the U.S. military’s plans to create 1,700 new beds for Ebola patients is inadequate and that there is a “rapidly closing window of opportunity for controlling the outbreak and averting a catastrophic toll.”

‘I’m Not Afraid of It’

U.S. military personnel will construct ETUs and fly cargo across Liberia but will not directly treat Ebola patients or come into contact with them. That is a point stressed by the Pentagon in trying to assuage the concerns of military families.

Instead, volunteer health-care workers will staff the 17 ETUs, which will not all be completed until December, a Pentagon spokeswoman said. The U.S. Agency for International Development, which is coordinating the overall effort, said late this week that 3,700 people from around the world had volunteered online to serve in West Africa. But it is unclear how many will make it through the vetting process, which USAID said is being handled by organizations such as the International Medical Corps, Save the Children, the International Organization for Migration and the International Rescue Committee.

A potential complication in recruiting health-care workers to fight Ebola arose Friday when the states of New York, New Jersey and Illinois announced they will quarantine for 21 days travelers from West Africa who have directly dealt with Ebola patients.

Related: 11 Ways to Fight Ebola and Other Diseases

A nurse, Kaci Hickox of Doctors Without Borders, was immediately detained Friday in New Jersey and quarantined in a hospital against her will. She has no Ebola symptoms, has tested negative for Ebola and is angry about her treatment, writing in the Dallas Morning News, “This is not a situation I would wish on anyone, and I am scared for those who will follow me.”

A key to attracting volunteers has been the promise that they will be given top-flight medical treatment if they get sick. To that end, the U.S. military is completing a 25-bed field hospital near the airport in Monrovia, the Liberian capital, expected open the first week of November.

It will be staffed by members of the Public Health Service, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. It is one of the seven uniformed services; members receive military pay and benefits, and their uniforms look like those of the Coast Guard, only with PHS insignia. The service’s officers fought yellow fever, cholera and plague in the early years of the 20th century and examined immigrants at Ellis Island. In recent years, they have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

About 65 PHS officers are scheduled to arrive in Monrovia this coming week and could stay for up to 60 days. They were handpicked for the mission and had the option of declining. But no one who was asked to go said no, according to an HHS spokeswoman.

Related: Ebola Scams Prey on the Public's Fear

“I’m respectful of the pathogen, but I’m not afraid of it,” said Capt. Calvin Edwards, 51, who will oversee the PHS team in Liberia. “It doesn’t hop from person to person. It requires contact with bodily fluid.”

Edwards works full time for the Food and Drug Administration in Harrisburg, Pa., overseeing food safety inspections. Married with four children, he lives in Chambersburg, Pa., and left for training in Alabama on Oct. 19, his 29th wedding anniversary. He bought his wife a dozen roses before he left and took the family out for dinner at the LongHorn Steakhouse.

Edwards said he is bringing the same New Testament he has brought on previous deployments, as well as a foam pillow that will remind him of home. To relax, he said, he will try to summon the sense memories of his new hobby, beekeeping. He will close his eyes in Liberia and imagine the smell of wax in the hive, and the buzzing of the bees.

The field hospital where he will work is a series of domed structures lined up on a campus the size of a football field. The hospital will have air conditioning, because U.S. medical staffers will be working in stifling-hot personal protective equipment. “When you are in full PPE, it’s like 90 to 100 degrees,” said Rear Adm. Scott Giberson, the acting deputy surgeon general, who is already in Monrovia. “Shift work is exhausting.”

Related: Obama Risks An Ebola Outbreak for His Own Ambitions

Cmdr. Anthony Tranchita, the head of a four-member team of behavioral-health specialists from the PHS, said he is bringing photos of his wife, 4-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter, plus a photo of a favorite spot in North Dakota where he and his father hunted this fall. It is a wooded area on the edge of an open field. It had just rained, and Tranchita had captured the soft glimmer of a rainbow.

He has mixed feelings about the mission. He is fulfilling an obligation, he said, “but there’s also some of that fear, some of that, ‘Wow, what is this going to be like?’ ”

Lt. Cmdr. Greg Raczniak, 40, who will be one of the doctors at the field hospital, is a clinician for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He has been in West Africa before and likes the cuisine there. He is thinking about rice with sauce, plantains with ginger, roasted chicken. He said his wife, a parasitologist, supports the mission. “She wishes she could take off law school to come with me,” Raczniak said. “This is what I’m trained to do. This is the life my wife and I have chosen.”

‘You Have to Stay Positive’

Military personnel are flying to Liberia from places such as Forts Campbell, Bliss, Hood, Carson and Benning, and the Aberdeen Proving Ground. Many do not know when, exactly, they will be airborne, or when they will return home, though they have been told they should expect a deployment lasting nine to 12 months.

Related: The Unthinkable for Hospitals - Withholding Ebola Care

Sgt. Jasmine Holmes, 24, of the 36th Engineer Brigade based at Fort Hood, is making the journey in the coming weeks and has taught herself how to prepare mentally: “You’ll come back soon — safe, healthy. It’s not going to last long. Those are the kinds of things you have to put in your head. You have to stay positive. You’re going to a country you’ve never seen before. It’s going to be a life experience.”

The military is supporting the hundreds of American civilians who have been fighting the Ebola outbreak for months in West Africa. They range from epidemiologists from the CDC to specialists in emergency logistics from the U.S. Forest Service.

Greg Thorne, the deputy team leader for the CDC in Liberia, wrote to Peace Corps Director Carrie Hessler-Radelet this past week, thanking the agency for smoothing the path for American public health workers in the county of Gbarpolu.

“We, the CDC team members, entered Gbarpolu as strangers,” Thorne wrote. “Carried by community goodwill . . . and connected by our Peace Corps colleague’s extensive local network, we were able to rapidly integrate with the county leadership and earn the trust necessary for them to openly discuss challenges and take our suggestions to heart.”

The Peace Corps staffers have relationships with local leaders, police officers, religious officials and fellow teachers. They know the local English dialects and have been interpreting for CDC workers and helping them understand local customs.

The Liberian civil war took away the country’s political infrastructure, said Samuel Sampson, a Liberian and the Peace Corps’s program manager for secondary education. He said credibility and political clout lie primarily with local people in each county. “You need to know these people,” Sampson said. “You need to know the gathering spots.”

George Karneh, another Liberian working with the Peace Corps, has also guided CDC teams into rural areas. “For me, I look at Ebola as a war,” Karneh said. “I look at it as an important mission, a lifesaving one. It’s going to be written in history that, once upon a time, we had this awful thing . . . and people were able to stand and fight it along with the CDC.”

The virus is just one of the many challenges for those flying into West Africa. Mosquitoes and malaria are another. Just getting around can be a challenge. The roads can be treacherous, particularly in the rainy season.

Sometimes there is no road, only a canoe. That is what CDC disease detective Katie Curran, 33, of Atlanta discovered in rural Sierra Leone. She has been making arduous trips into the bush to meet with village leaders and discuss ways to contain the outbreak. One day recently, she traveled with a team of health-care workers to a remote village that could be accessed only by crossing a river in a one-person dugout canoe. At the village they met the chief, who was wearing a Pittsburgh Steelers cap.

To get to the next village they had to cross another river, this time in a larger dugout. At the end of a long working day, she invariably eats dinner in her guesthouse. “We don’t have reliable Internet,” Curran said. “We don’t have reliable power. We don’t have reliable water. We have to travel very long distances on bumpy roads.”

She is making an observation, not complaining. She said she is enjoying the experience and is in awe of her colleagues. And it is simply not true, she said, that everyone in West Africa is dying of Ebola. “It’s not as scary as you think,” Curran said. “I think it’s scarier in the U.S. watching the news.”

Brady Dennis and Alice Crites contributed to this report, which originally appeared in The Washington Post.

Read more in The Washington Post:

Elon Musk: 'With Artificial Intelligence We Summon the Demon'

Eric Betzig Just Revolutionized Microscopy Again

Ebola Crisis Rekindles Concerns About Research in Russian Military Labs