In the policy debates over the social safety net, those in favor of reducing federal assistance to the poor often argue that transfer payments, like food stamps, rent subsidies, and unemployment insurance, do little to reduce poverty.

Many conservatives, for example, point to the vast amounts of money spent for very little in return. Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT), said last week, “For 50 years we’ve been fighting a war on poverty. For 50 years we’ve spent trillions of dollars on massive federal welfare programs that have largely failed.”

Earlier this year, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) released a much-discussed anti-poverty plan that would merge 11 fragmented programs into a single grant program for states. He claimed, “Federal programs are not only failing to address the problem. They are also in some significant respects making it worse.” Yet Ryan has also acknowledged that it’s unfair to abruptly cut off recipients from federal assistance when they reach a certain income threshold, and that it’s better to taper off the payments as income rises, reducing people’s disincentive to find work.

Some new research from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) offers another perspective on the ongoing debate.

Related: Businesses Upbeat About Jobs, Economic Growth

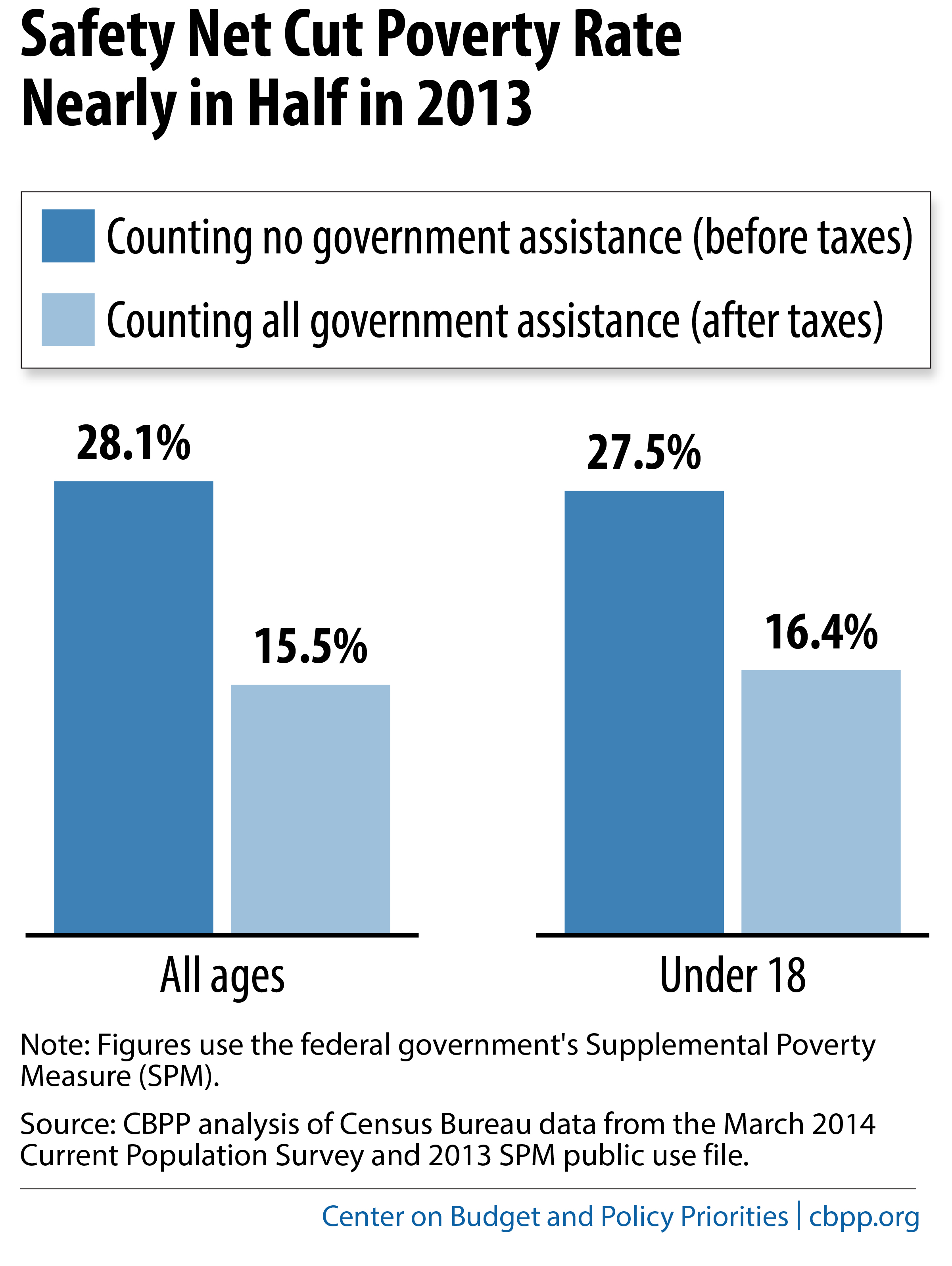

Examining 2013 U.S. Census Data, CBPP senior research analyst Danilo Trisi determined that in that year alone, payments from the various programs that make up the social safety net lifted 39 million people out of poverty. That included 8 million children.

Part of the disconnect is that the government’s official poverty figure doesn’t take all safety net benefits into account. It omits things like non-cash assistance and tax-based benefits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit. That means people are considered to be below the poverty line even when federal and state transfer payments raise their total income above poverty levels.

The official poverty measure has created a convenient talking point for opponents of the safety net. They often cite that figure instead of the Census Department’s more accurate Supplemental Poverty Measure, which takes all the benefits of the social safety net into account.

But Trisi’s findings show that when all safety net programs are considered, they account for a drop in the poverty rate from 28.1 percent to 15.5 percent.

“Non-cash and tax-based benefits now constitute a much larger part of the safety net than 50 years ago, so the official poverty measure’s exclusion of them masks the nation’s progress in reducing poverty over the last five decades,” Trisi writes.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: